Politics

Labour risks leaving its voters behind over settlement proposals

Following policy announcements from Labour, the Conservatives and Reform UK that would either make it more difficult or impossible for migrants to obtain Indefinite Leave to Remain in the UK, Heather Rolfe explores how the public feels about these proposals.

Since 2010, when David Cameron made his party’s pledge to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands, politicians have focused on reducing immigration numbers. But now the focus of political debate has widened to whether Britain should keep the migrants it has already attracted. Labour, the Conservatives and Reform UK are competing to make it harder for migrants to become British.

Extending the qualifying period for Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR) is a key proposal of the government’s 2025 white paper on immigration, which the Home Secretary expanded on in her speech in November. It espouses the principle of ‘earned settlement’ and proposes to increase the period of eligibility for settlement from five to ten years. The proposed new conditions on citizenship, which can follow a year after ILR, include: higher English proficiency, ‘community contribution’, employment and no debtor benefit claims.

Earlier in 2025, the Conservative Party made a similar proposal to extend the settlement route to ten years, plus a further wait of five years for citizenship. Taking both parties’ proposals a big step further, in September Nigel Farage announced Reform’s plan to abolish ILR altogether.

The other two main parties have opted out of the race: the Greens propose a five-year period of eligibility for all. The Liberal Democrats have suggested no change.

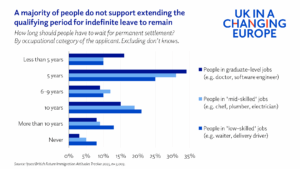

We asked respondents to the British Future/Ipsos Immigration Attitudes Tracker how long people should have to live and work in the UK before they can apply for permanent residence and then citizenship. They were asked to answer in relation to three occupational categories: people in graduate jobs, e.g. doctors or software engineers; people doing ‘mid-skilled’ jobs, e.g. chefs, plumbers and electricians; and people doing ‘low-skilled’ jobs, e.g. waiters and delivery drivers.

For each of these occupational categories, the most popular response is to keep the waiting period at five years. In the case of highly skilled migrants, half of respondents chose either keeping it at five years, or five years or less. Retaining or reducing the current ILR route is less popular among other groups, however, with 40% opting for five years or less for mid-skilled workers, and 35% for low-skilled migrants.

The government’s proposal for a ten-year waiting period is supported by around 20% of respondents in the case of mid- and low-skilled migrants, and 15% for high-skilled. Few people think that migrants should wait more than 10 years, though the option of 6-9 years has some support. The option of removing ILR and never allowing permanent settlement, as proposed by Reform UK, has very low levels of support, at 3%, 5% and 8% respectively for the named skill categories.

Younger people and ethnic minorities are more likely to prefer a wait of 5 years or less. But the most striking differences are political, with Labour, Green and Liberal Democrat voters in favour of shorter routes and Reform UK and Conservatives favouring longer ones.

Extending the qualifying period for ILR to ten years has more support among Conservative voters than any other group: almost a third (31%) support this change for lower skilled workers. More stringent requirements are less popular among Conservatives, with few (9%) supporting ending ILR altogether for lower skilled migrants (4% for mid-skilled and 2% for highly-skilled). The ten-year policy has less appeal for Reform UK supporters, who prefer tougher restrictions, particularly for lower-skilled migrants. 45% believe they should wait more than ten years or never be able to obtain ILR, compared to 20% who support extending the qualifying period to ten years for that group.

When it comes to Labour’s own supporters, the five-year route is more popular than its proposal for a ten-year wait, even for low-skilled workers. Around two-thirds of Labour voters prefer a period of less than 10 years for high- and medium-skilled workers (62% and 68%), and more than half for lower skilled (54%). Of those favouring a longer period, most prefer ten years rather than more or never.

Among the public overall, Reform UK’s proposal to end ILR altogether has very little support: only 3% and 5% of respondents respectively say high and medium skilled migrants should never be allowed to settle in the UK. Only 8% of the public believe that low-skilled migrants should never have settlement rights.

Reform UK’s proposal to end settlement also has limited support among its own voters, except in the case of low-skilled workers. 21% support the policy in relation to this group. Only 6% support ending settlement for highly skilled migrants and 12% for those in mid-skilled roles. For other skill groups, Reform UK’s voters prefer a long route of more than 10 years to ending settlement completely.

Of the three parties with proposals on ILR, Labour’s are most at odds with its own supporters, who prefer the status quo. The party risks losing support through both the proposal and accompanying messaging. Since Liberal Democrat and Green Party voters have similar preferences, Labour is unlikely to win their support with its new proposals. Labour’s plans on settlement are also likely to turn off young people and ethnic minorities who are much less likely than others to support extending the route to ILR.

The public more widely is least supportive of extending the ILR waiting period for higher skilled migrants. This could lend support to the notion of ‘contribution’ within the white paper proposals. It is also likely to reflect a realistic view of the role of migrants in key sectors and services. Most people would like numbers of new migrants to increase or stay the same in skilled occupations including medicine, nursing and engineering: tighter restrictions on ILR are likely to lead to fewer arrivals, and more churn in these sectors.

Labour faces two main risks from going ahead with its ILR proposals: the first is further drift of voters to Liberal Democrats and Greens, evident from a number of opinion polls this year. The second is the potential harm to provision of key services and to economic growth. To avoid these dangers. The government could use the white paper consultation period to review the potential political and economic costs of its settlement proposals.

By Dr Heather Rolfe, Director of Research, British Future.