Politics

Labour’s asylum appeals overhaul: what the new system means in practice

Ali Ahmadi, Catherine Barnard, Fiona Costello explain what Labour’s proposals to overhaul the asylum appeals process will mean in practice.

In November 2025 the Home Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, introduced her ‘Restoring Order and Control’ policy, branded as the ‘most sweeping asylum reforms in modern times’. This included an overhaul of the appeals system, currently considered too slow and expensive, allowing asylum seekers to ‘bounce around’, lodging appeal after appeal. So, how does the current appeals system work, what does the government want to change, and will it work?

Under the current system, if the Home Office refuses an asylum claim, an appeal can be made to an independent First-tier Tribunal, unless the case is classed as ‘clearly unfounded’. The tribunal then reviews the case fully, including any new evidence. This process is slow. The backlog of asylum appeals stood at around 51,000 in early 2025 and waiting times averaged 54 weeks.

If the appeal fails at Tribunal stage, the applicant can seek a further appeal, but only regarding a point of law, not because they disagree with the decision. In exceptional cases, the case can go as far as the Supreme Court, but again only on points of general or constitutional legal significance, not based on the outcome of the decision itself. While appeals are ongoing, the person cannot be removed from the UK.

Once all UK appeals have been exhausted, the case can be taken to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). In urgent situations, an asylum seeker can ask the ECHR to temporarily stop their removal – under an interim measure (or Rule 39 order) – but such orders are very rare; there were no orders against the UK concerning asylum cases in 2023 or 2024.

If an asylum seeker has no right to appeal, or has already exhausted all appeal options, they may ask a court for a Judicial Review (JR). A JR does not re-examine the asylum claim but instead examines the lawfulness of the decision on the grounds of illegality, irrationality, or procedural unfairness. Applying for JR does not stop removal from the UK.

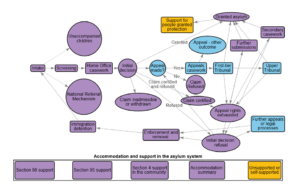

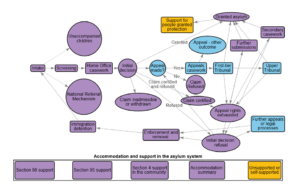

Fig 1: Data Visualisation Map of Asylum System (NAO, 2025). Available here. Purple on the map = Home Office responsibilities, blue = Ministry of Justice responsibilities and Yellow = local authority responsibilities.

As the map in figure 1 shows, the asylum system in the UK is a complex and highly legal process. Many asylum seekers struggle with the system, especially given the difficulty of getting legal aid. In the year ending March 2024, at least 57% of main applicants (over 54,000 people) claiming asylum or appealing a refusal at the First-tier Tribunal were unable to access a legal aid representative in England and Wales.

Nevertheless, in 2024, over 36,500 asylum appeals were lodged at the First-tier Tribunal and, of the cases heard, 48% were won by the appellant. The data is patchier for the Upper Tribunal, due to the introduction of a new case management system. However, in 2021/22 about 30% of the appeals were successful. Success rates decrease as cases continue upward. However, the high success rate at the first tier indicates poor initial decision-making rather than widespread abuse of appeals system.

This is not the government’s view. It says the current asylum system costs more than £5 billion a year, much of it on hotel accommodation (needed while appeals are caught in the backlog of cases outlined above), and it allows failed claimants, including some foreign-national offenders, to delay removal for long periods. Under the new plan, to be set out in the Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill, there will be one single appeal where every possible ground (asylum/humanitarian protection, human-rights claims, new evidence, etc.) must be raised at once. A new Independent Appeals Body, to be staffed by specially trained adjudicators, will hear these cases. Once that appeal is decided it will normally be final.

This new system is to be modelled partly on the Danish system. Denmark’s Refugee Appeals Board does deliver final decisions quickly and has very few onward challenges. However, Denmark also has far higher initial grant rates (around 65–70 per cent) than the UK (47%) and invests heavily in high-quality first decisions. By contrast, rapid processes introduced by the Sunak government have not led to good decision-making and thus to a large number of (successful) appeals, as noted above.

In the UK’s new system, early free legal advice will be provided so that people can put forward their strongest case the first time. The success of the new system will depend heavily on whether this early advice is genuinely accessible and of high enough quality, a major challenge given the current shortage of immigration lawyers outside London.

To make the single-appeal rule stick, the law will also change in following ways:

- Family-life claims (under Article 8 of the ECHR) will succeed in future only if the person has very close family in the UK, such as minor children or dependent parents, and the public interest in removal will carry much greater weight.

- The use of Article 3 ECHR (on inhuman or degrading treatment) to block removal on health grounds will be narrowed.

- Late claims of being a victim of modern slavery or trafficking will carry less weight.

- Appeals involving accommodation or foreign-national offenders will be expedited.

Fresh claims will remain possible if appellants can show that the claim is ‘substantially different’ from their initial claim and justify why the matter is being raised late. JRs will also still exist, and by compressing all issues into a single appeal and narrowing human rights protections, the reforms are likely to push more people toward them. Yet requesting a JR is complex, and securing legal aid for JR is extremely difficult. If an applicant has had an appeal on the same or a closely related issue within the last 12 months, they will not qualify for legal aid for a JR.

In conclusion, the proposed reforms aim to replace a multi-layered system that currently overturns roughly half of Home Office refusals with a faster, one-chance process that is intended to be final in almost every case. Whether this will reduce delays and costs without increasing the risk of wrong decisions will be the central question about the reforms as the Bill moves through Parliament in 2026.

By Catherine Barnard, Senior Fellow, UK in a Changing Europe & Professor of EU Law and Employment Law, University of Cambridge, Fiona Costello, Assistant Professor, University of Birmingham and Ali Ahmadi, Research Associate, University of Cambridge and PhD student at Anglia Ruskin University.