Politics

The sleeping dog of UK-EU finances

Simon Usherwood explains financial flows between the UK and the EU since the UK’s withdrawal and how they may be affected by the UK-EU reset.

It is rare these days to see media stories about the finances of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union.

Yet, following the release of the Office for National Statistics’ annual Balance of Payments report (the ‘Pink Book’), the Daily Mail was moved to report an ‘eye-watering’ £50 billion total that is now expected to be paid as the UK settles its accounts following the end of its membership in January 2020.

At one level, this is not news: as the story itself set out, almost all of this amount was agreed under the 2020 Withdrawal Agreement, to cover commitments made during membership, as well as long-running futures for things like pensions of British nationals who worked for the EU’s institutions. This has attracted almost no media or political attention in the intervening period.

On the other hand, the Mail is correct to note that the total is now pegged to be higher than originally expected. So what’s going on?

It’s useful to start with trying to pin down just how much money is involved, since estimates have varied.

At the time of withdrawal, a range of calculations were made on the basis of the formulas contained in the Withdrawal Agreement. British valuations ranged from £30bn to £39bn, while the Commission’s evaluation was just over €40bn (£34m based on exchange rates at the time).

Since then, various revisions have been required, driven by factors as varied as the relative size of the UK economy to that of the EU27, the success (or not) of British applications for EU funding (and their spending of that funding) and a number of cases before the EU’s Court of Justice. The latter have generated both penalties for British infringements of EU rules and payments back to the UK for infringements caused by companies during the period of UK membership.

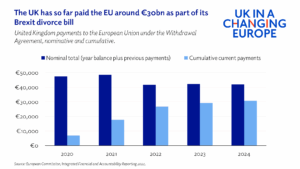

However, all of these figures have sat broadly within expectations since 2020. The EU’s annual reports on the Union’s finances provide the most detailed breakdown of how the UK’s Withdrawal Agreement payments have been structured. To the end of 2024, these total just under €30 billion, with roughly €11 billion still liable in coming years.

These figures closely match the total expenditure for 2020-24 in the ONS’ Pink Book, which total £26.4 billion or roughly £6.5 billion a year.

For context, in the years prior to leaving the EU, the UK was making net payments of over £10 billion a year. As can be seen in this graph, last year’s figures put the UK firmly back towards the situation that applied around the time of the 1993 Maastricht Treaty, before enlargement to Central and Easter Europe necessitated larger budget contributions. Moreover, unlike then, the bulk of Withdrawal Agreement liabilities are now discharged.

All of this said, it is also clear that we are entering a new phase of financial relations between the two parties.

The Withdrawal Agreement was concerned solely with winding up liabilities. But as the UK has started to develop new links with the EU, so too has it generated new financial obligations.

Central in these is participation in EU programmes. Since 2024, the UK has been fully associated with the Horizon Europe research programme. Already in the first year of that association, British-based institutions secured €735 million in funding, making it the fifth most successful of the 47 states participating.

Such success creates financial obligations too. The main delay in agreeing UK participation during 2023 was due to Commission and Treasury demands for an equitable finance mechanism that would ensure, broadly speaking, that the UK would pay a similar amount to what it put in. The expectation had been that British applicants would be relatively successful – as has proved – but the final agreement was also exceptional ensuring that any significant British over-payment would be reimbursed.

Similar principles are likely to apply to any future programmes that the UK signs up to, including the Erasmus + scheme for student and researcher mobility, which was included in May’s Common Understanding.

As these schemes multiply, and as individual financial reconciliation mechanisms kick in, so too will the volume of financial flows between the UK and EU. Already in 2024, you can start to see this in the last graph with the arrival of nearly £1.2 billion in research grants to the UK.

An upshot of this is that next year’s Pink Book will show a further rise in the amounts paid by the UK to the EU, as the cycling of programme support funding joins Withdrawal Agreement streams.

But the extent of non-interest in finances to date should not be taken as a given.

As withdrawal recedes into the past, and a small, but not trivial, amount continues to flow to Brussels under the Withdrawal Agreement terms, so questions might start to grow about whether this can still be justified, especially if the national budget continues to be tightly squeezed.

The indication that the EU will also seek British contributions to the EU budget in return for cooperation on removing food checks, allowing energy trading and participating in defence procurement will also make for more headlines.

Of course, in comparison to the many challenges facing the Chancellor ahead of this autumn’s budget, the roughly €1.5 billion due to the EU next year is a rounding error. However, for most members of the public that still sounds like a lot of money.

Add to this whatever gross amount is paid for participation in EU programmes and it is possible to imagine something close to a re-run of the referendum bus saga.

Whether this government, or its successors, will be better able to communicate the value of such financial flows remains to be seen, but as long as it lacks a strong overall narrative for its EU policy this seems less than likely.

By Simon Usherwood, Professor of Politics and International Studies, The Open University and Senior Fellow, UK in a Changing Europe.