Politics

Who is emigrating from the UK?

John Mahon makes the case for having a better understanding of the British nationals leaving the UK. He argues that the cost to the state of British nationals leaving or returning to the UK varies, so it should develop a clearer strategy to deal with the impact of emigration.

The ONS recently updated and improved their methodology for measuring British nationals leaving the UK. This is a welcome development. Using databases linked to National Insurance numbers and other techniques, they now estimate that, each year, about 250,000 British people emigrate and about 150,000 come back to the UK. This is higher than the previous measurement, using the International Passenger Survey, of ~160,000 emigrants and ~80,000 returnees.

So, last year 400,000 British Nationals made a decision to leave or return – what do we know about these people? Depending on who you listen to it’s either millionaires leaving for tax havens in the Middle East, newly retired folk moving to the warmer climates, or junior doctors and newly qualified medical students moving to Australia for better pay and conditions. But the reality is that we just don’t know.

Like many wealthy democratic states, there is no formal process for UK citizens to emigrate. A PAYE taxpayer can just leave. A self assessment tax payer has a short form to fill in (SA109). Returning after years away is also very simple. The tax office will just pick up again on PAYE and your access to all the services and benefits (NHS, welfare, education) are quickly restored. There may be a Habitual Residence Test to prove you qualify for means-tested benefits but a simple tenancy agreement, a GP registration or a UK bank account will easily suffice for a UK citizen.

For public policy reasons and Treasury planning, it would be much better if we knew something about these citizen-emigrants. How old are they when they leave? For those that return – how long are they away? What part of the UK are they from? What is the income distribution of those leaving?

There are a range of outcomes to the public purse depending on some of the answers to those questions. A person whose working life was in the UK but retires overseas may reduce the cost to the state in healthcare and social care, even after receiving their UK pension. A 30-year-old professional working abroad for 10-15 years and then returning reduces the tax take to the state – by not being in the UK when, typically, their taxes exceed their cost to the state. Given we are talking about 250,000 people leaving and 150,000 returning they don’t all have to be millionaires to have a significant impact on the state’s finances.

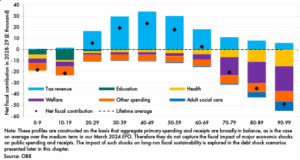

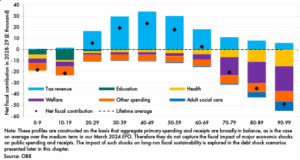

Consider the table below produced by the OBR showing the average fiscal contribution by age. This shows the average tax receipts and average costs, such as healthcare, education etc. by age. So, a person leaving at the age of 30 and returning at the age of 40 will typically result in the state missing out on £193,000 over those 10 years. Whereas someone who emigrates at the age of 60 and dies at the age of 85, will ’save’ the state £358,000 (assuming no pension is paid overseas).

If we think that emigrants are often at the higher end of the income distribution (perhaps due to the immigration restrictions of the destination country), then these costs could be much higher. So, an OBR or Treasury estimate cannot just rely on a simple net emigration estimate – the fiscal impact will be highly dependent on the age and income profile of the emigrants and their likelihood to return.

To some, registering your emigration and subsequent re-immigration feels like an infringement of your right to emigrate – an unnecessary intrusion maybe, even an obstacle. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) says, in Article 13, that “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country”. However, one can agree with the principle but still put in some bureaucratic process for the benefit of your fellow citizens. The UDHR also says that there is the right to marry and have a family but there seems to be very little objection to registering births and marriages.

With greater understanding, we can start to think about some current and future challenges and opportunities. For example, there are 1.1 million pensioners receiving their UK pension abroad. Many live in Australia or North America but approximately 480,000 live in EU countries. Given their geographic proximity perhaps we should think about many of these older citizens returning due to climate change, political or other factors. What would 100,000 pension aged returnees do to housing, care home capacity, social care services?

We could look at graduates and their reasons for leaving. Are graduates emigrating to accelerate their early career progression, to return later – or are they emigrating for good? Do we want to, as a society, put in place incentives for graduates to remain?

As to the question of whether emigration is too high or too low – this government and previous ones don’t seem to have an opinion. In 2019 in the UN completed a survey on International Migration. Each country was asked a series of questions on their migration policies and institutions. One question was whether they had “A national policy or strategy on the emigration of its citizens”. The UK, along with most wealthy developed countries, said “No”. With 4.8 million UK-born citizens now living elsewhere, perhaps it’s about time to develop one and the starting point needs to be much better data on emigration.

By John Mahon, PhD candidate, King’s College London.