The media is full of breathless reports that AI can now code and human programmers are going to be put out to pasture. We aren’t convinced. In fact, we think the “AI revolution” is just a natural evolution that we’ve seen before. Consider, for example, radios. Early on, if you wanted to have a radio, you had to build it. You may have even had to fabricate some or all of the parts. Even today, winding custom coils for a radio isn’t that unusual.

But radios became more common. You can buy the parts you need. You can even buy entire radios on an IC. You can go to the store and buy a radio that is probably better than anything you’d cobble together yourself. Even with store-bought equipment, tuning a ham radio used to be a technically challenging task. Now, you punch a few numbers in on a keypad.

The Human Element

What this misses, though, is that there’s still a human somewhere in the process. Just not as many. Someone has to design that IC. Someone has to conceive of it to start with. We doubt, say, the ENIAC or EDSAC was hand-wired by its designers. They figured out what they wanted, and an army of technicians probably did the work. Few, if any, of them could have envisoned the machine, but they can build it.

Does that make the designers less? No. If you write your code with a C compiler, should assembly programmers look down on you as inferior? Of course, they probably do, but should they?

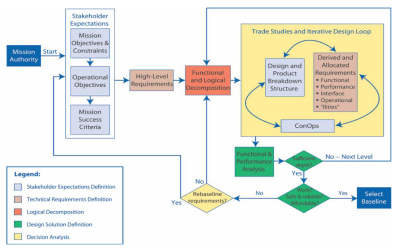

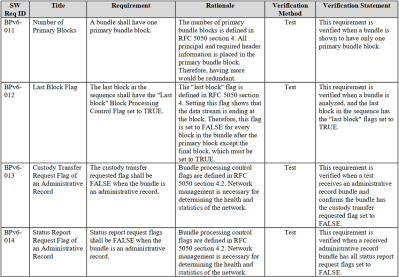

If you have ever done any programming for most parts of the government and certain large companies, you probably know that system engineering is extremely important in those environments. An architect or system engineer collects requirements that have very formal meanings. Those requirements are decomposed through several levels. At the end, any competent programmer should be able to write code to meet the requirements. The requirements also provide a good way to test the end product.

Anatomy of a Requirement

A good requirement will look like this: “The system shall…” That means that it must comply with the rest of the sentence. For example, “The system shall process at least 50 records per minute.” This is testable.

Bad requirements might be something like “The system shall process many records per minute.” Or, “The system shall not present numeric errors.” A classic bad example is “The system shall use aesthetically pleasing cabinets.”

The first bad example is too hazy. One person might think “many” is at least 1,000. Someone else might be happy with 50. Requirements shouldn’t be negative since it is difficult to prove a negative. You could rewrite it as “The system shall present errors in a human-readable form that explains the error cause in English.” The last one, of course, is completely subjective.

You usually want to have each requirement handle one thing to simplify testing. So “The system shall present errors in human-readable form that explain the error cause in English and keep a log for at least three days of all errors.” This should be two requirements or, at least, have two parts to it that can be tested separately.

In general, requirements shouldn’t tell you how to do something. “The system shall use a bubble sort,” is probably a poor requirement. However, it should also be feasible. “The system shall detect lifeforms” doesn’t tell you how to make that work, but it is suspicious because it isn’t clear how that could work. “The system shall operate forever with no external power” is calling for a perpetual motion machine, so even if that’s what you wish for, it is still a bad requirement.

You sometimes see sentences with “should” instead of shall. These mark goals, and those are important, but not held to the same standard of rigor. For example, you might have “The system should work for as long as possible in the absence of external power.” That communicates the desire to work with no external power to the level that it is practical. If you actually want it to work at least for a certain period of time, then you are back to a solid and testable requirement, assuming such a time period is feasible.

You can find many NASA requirements documents, like this SRS (software requirements specification), for example. Note the table provides a unique ID for each requirement, a rationale, and notes about testing the requirement.

Requirement Decomposition

High-level requirements trace down to lower-level requirements and vice versa. For example, your top-level requirement might be: “The system shall allow underwater research at location X, which is 600 feet underwater.” This might decompose to: “The system shall support 8 researchers,” and “The system shall sustain the crew for up to three months without resupply.”

The next level might levy requirements based on what structure is needed to operate at 600 feet, how much oxygen, fresh water, food, power, and living space are required. Then an even lower level might break that down to even more detail.

Of course, a lower-level document for structures will be different from a lower-level requirement for, say, water management. In general, there will be more lower-level requirements than upper-level ones. But you get the idea. There may be many requirment documents at each level and, in general, the lower you go, the more specific the requirements.

And AI?

We suspect that if you could leap ahead a decade, a programmer’s life might be more like today’s system architect. Your value isn’t understanding printf or Python decorators. It is in visualizing useful solutions that can actually be done by a computer.

Then you generate requirements. Sure, AI might help improve your requirements, trace them, and catalog them. Eventually, AI can take the requirements and actually write code, or do mechanical design, or whatever. It could even help produce test plans.

The real question is, when can you stop and let the machine take over? If you can simply say “Design an underwater base,” then you would really have something. But the truth is, a human is probably more likely to understand exactly what all the unspoken assumptions are. Of course, an AI, or even a human expert, may ask clarifying questions: “How many people?” or “What’s the maximum depth?” But, in general, we think humans will retain an edge in both making assumptions and making creative design choices for the foreseeable future.

The End Result

There is more to teaching practical mathematics than drilling multiplication tables into students. You want them to learn how to attack complex problems and develop intuition from the underlying math. Perhaps programming isn’t about writing for loops any more than mathematics is about how to take a square root without a calculator. Sure, you should probably know how things work, but it is secondary to the real tools: creativity, reasoning, intuition, and the ability to pick from a bewildering number of alternatives to get a workable solution.

Our experience is that normal people are terrible about unambiguously expressing what they want a computer to do. In fact, many people don’t even understand what they want the computer to do beyond some fuzzy handwaving goal. It seems unlikely that the CEO of the future will simply tell an AI what it wants and a fully developed system will pop out.

Requirements are just one part of the systems engineering picture, but an important one. MITRE has a good introduction, especially the section on requirements engineering.

What do you think? Is AI coding a fad? The new normal? Or is it just a stepping stone to making human programmers obsolete? Let us know in the comments. Although they have improved, we still think the current crop of AI is around the level of a bad summer intern.