Uncategorized

The new media is still a good thing

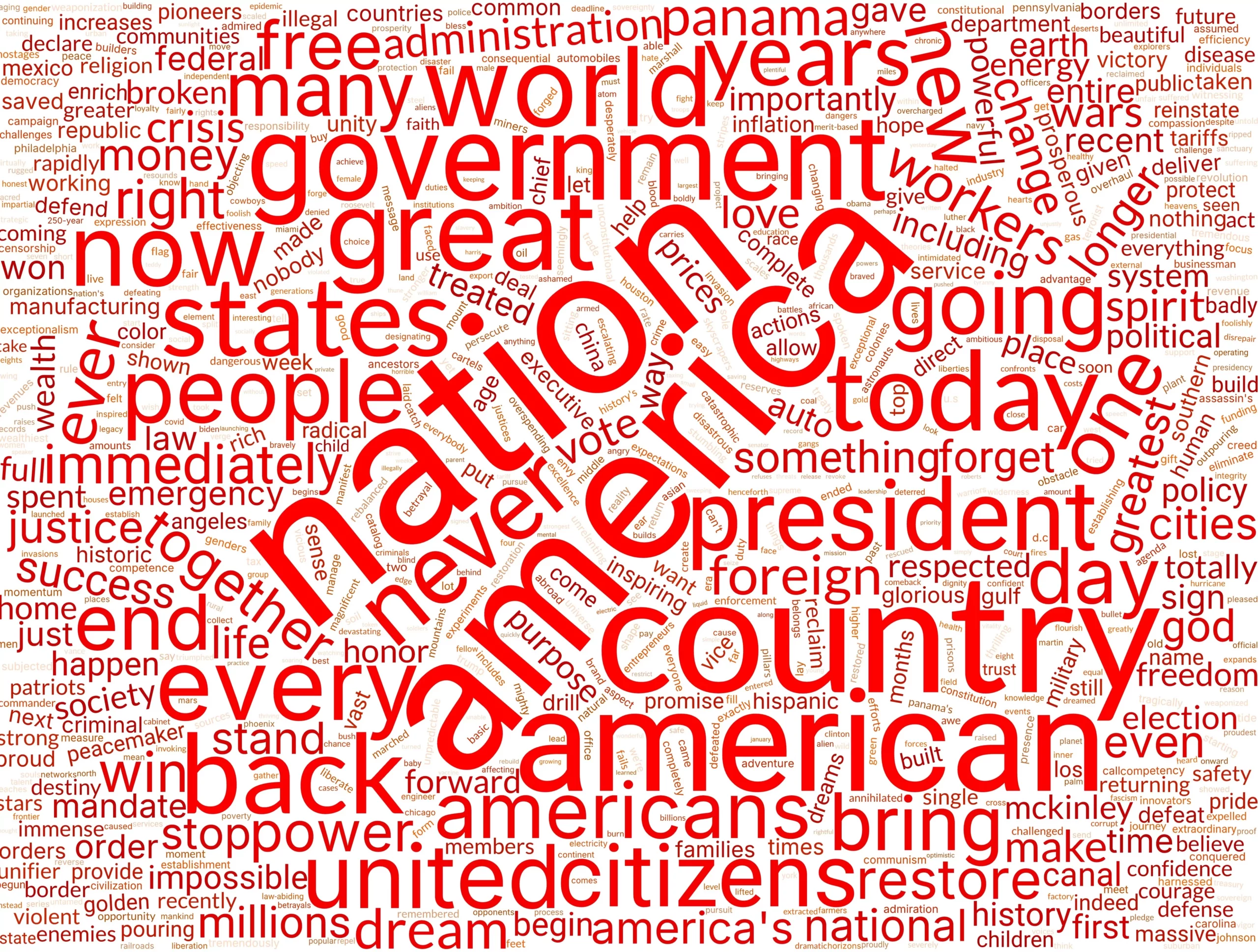

I’d like to offer Konstantin Kisin a dose of optimism. As Kisin feels his high hopes for the era of new media slipping away, the predictable costs of democratizing journalism are still firmly outweighed by the benefits.

Writing this week on the debate Joe Rogan hosted between Douglas Murray and Dave Smith, Kisin reflected on his own excitement about the dissolving power of legacy media.

“After all, what could go wrong with ‘democratizing information’?” he asked. “Well, as it turns out, quite a lot.”

Kisin argued that “incentive structures and thought patterns we typically associate with the entertainment business are not the same as those we expect to see in journalism or academia.”

“Just as the assumptions of the elite class were proved wrong by the actions of their fellow citizens during the era of Trump, Brexit, and Covid-19, the assumptions some of us held about the future of the media are now crumbling before our very eyes,” he said of “Podcastistan,” the land we critics of legacy gatekeepers hath wrought.

Finally, Kisin concluded, “The world of entertainment is not driven by truth-seeking, and the claim that someone’s ideas are false is no longer an effective critique. Podcastistan is a place where people scold the mainstream media for failing to live up to their standards on honesty and accuracy while having none of their own.”

While I disagree totally with Kisin on the validity of Murray’s argument against Smith — and I’m not sure I agree with his assessment of Darryl Cooper — it’s clearly true that our democratized media landscape is a messier one, in which a rational distrust of experts has driven audiences to some bad actors more interested in entertainment than truth. Those bad actors also have tools that allow them to compete on a more even playing field with the Old Guard. You can do the trick with a cheap USB microphone and some TikTok know-how, or a small budget for audio equipment, or a knack for exploiting the X algorithm.

The central source of Kisin’s disappointment with new media seems to be that “incentive structures and thought patterns we typically associate with the entertainment business are not the same as those we expect to see in journalism or academia.” As Anchorman 2 ably reminded us, this sentiment has been leveled, with varying degrees of validity, throughout the history of modern journalism.

So what’s different now in the world of the “podcast election”? It’s absolutely true that the line is blurrier than it ever has been, and it’s more difficult for people outside the media to discern who’s serious and who’s not. To Kisin’s point, this is great for people who wish to exploit institutional distrust by turning comedy careers into political podcasts or history obsessions into amateur YouTube channels.

However, Kisin assumed people blindly accept every word uttered by Cooper and Ian Carroll or even accept the thrusts of their arguments. I’d rather live in a world in which people who don’t trust mainstream historians can listen to Cooper and Murray, read their criticisms, and weigh the evidence. Some people seek out Cooper because they’re bigots, but some people seek him out because they’re entertained by history and curious about alternative perspectives. They listen to a lot, and they read a lot.

Listening to Cooper sent me back into the long-running debate about Winston Churchill. I emerged with a fuller, more dimensional appreciation for him, not a deep hatred of the West. Listeners are capable of and interested in weighing the perspectives of legitimate experts, such as Andrew Roberts, with the perspectives of comedians. Sometimes people might side with the comedians, and sometimes they may be correct. However, while the economic incentive structures in new media may further decrease the volume of experts, it’s not silencing them or stripping away their credentials. It’s just allowing for more comparisons.

I’m not sure that’s ideal, but neither was the status quo. Now, people have to work hard to weigh competing reports and arguments rather than relying on the evening news or morning paper to present both sides and reliable experts. So, while today that means we sometimes take ideas too seriously when they deserve less weight, in the past, we often failed to question the prevailing narratives because they were presented with utter confidence.

TRUMP’S CHAOTIC EUROPEAN DEFENSE SPENDING MESSAGING

There is no perfect system, and new media will create plenty of additional problems for consumers and society at large. However, it’s forcing the old guard to compete, and if journalists and academics are worthy of earning back the public’s trust, they ultimately will win in the marketplace. People like entertainment, but if they want the truth from sources who aren’t providing it, they’ll move right along. We know because it’s happened before.

No matter how entertaining Don Lemon was in 2018, we eventually tuned him out. His YouTube channel could double its meager views, and he wouldn’t have the influence he once wielded.

Uncategorized

Trent Alexander-Arnold: Curtis Jones pays tribute to Liverpool team-mate

Liverpool midfielder Curtis Jones pays tribute to his departing team-mate Trent Alexander-Arnold following the Reds final game of the season a 1-1 draw against Crystal Palace at Anfield.

MATCH REPORT: Liverpool 1-1 Crystal Palace

Available to UK users only.

Uncategorized

Football gossip: Garnacho, Mitoma, Gyokeres, Martinez, Raya, Mason

Napoli want to sign Alejandro Garnacho after missing out on the Argentine in January, Arsenal join Bayern Munich in the pursuit of Kaoru Mitoma, Viktor Gyokeres will leave Sporting this summer.

Napoli sporting director Giovanni Manna is set to meet with Manchester United over a possible deal for 20-year-old Argentina winger Alejandro Garnacho, who was the subject of a rejected £40m bid from the Italian champions in January. (i paper), external

Arsenal have joined Bayern Munich in the race to sign Brighton‘s 28-year-old Japan midfielder Kaoru Mitoma. (Sky Germany), external

Sweden forward Viktor Gyokeres will leave Sporting this summer. The 26-year-old is linked with Arsenal and Chelsea and has an agreement with the Portuguese club to allow him to leave for less than his £84m release clause. (Sky Sports), external

Arsenal want Aston Villa‘s Argentina goalkeeper Emiliano Martinez, 32, to return to the club amid interest from Real Madrid in their 29-year-old Spain shot-stopper David Raya. (Sun), external

Tottenham assistant manager Ryan Mason is the leading candidate to become West Brom boss. (Talksport), external

Leicester City have made a bid to sign 18-year-old Guinean forward Abdoul Karim Traore from French club Bourg-en-Bresse. (Foot Mercato – in French), external

Arsenal want Ghana defensive midfielder Thomas Partey to remain with the club beyond his current deal, which expires in the summer, despite being linked with Real Sociedad’s 26-year-old Spain midfielder Martin Zubimendi. (football.london), external

Napoli have offered 33-year-old Belgium midfielder Kevin de Bruyne a £23m salary over a three-year deal following his departure from Manchester City this summer. (Fabrizio Romano), external

Napoli president Aurelio de Laurentiis has confirmed the club’s interest in De Bruyne. (II Mattino, via Mirror), external

Arsenal sporting director Andrea Berta has held talks with AC Milan winger Rafael Leao, 25, in a bid to persuade him to move to Emirates Stadium this summer. (TeamTalk), external

Norwich City have approached Bristol City manager Liam Manning over potentially taking charge at Carrow Road next season. (Telegraph – subscription required), external

Arsenal have made an offer to sign 21-year-old RB Leipzig forward Benjamin Sesko. (Fichajes – in Spanish), external

Uncategorized

Ruud van Nistelrooy: Leicester manager says ‘no talks’ yet on future

Leicester manager Ruud van Nistelrooy says he has not yet had any talks with the club about his future but that they “need to happen”.

The Dutchman signed a contract until June 2027 and is understood to want to remain in charge of the Foxes, but reports say former Southampton boss Russell Martin is a contender to take his job.

Already relegated Leicester bowed out of the Premier League on Sunday with a 2-0 defeat at Bournemouth.

The Leicester boss said he “hopes to speak” with the club about his future following relegation to the Championship.

“I would like to talk and that’s the first thing that needs to happen,” he told BBC Match of the Day.

“It’s been silent and it’s something towards the end of the season, get things done with and then I expect to hear something.”

Leicester finished the season in 18th place, 13 points adrift of safety, and were relegated in April.

He added: “It’s important to start talking and to see how we look into the future. It’s what you need to find out. So far there hasn’t been any conversation but I’m waiting for that to happen.”

-

Entertainment21 minutes ago

Entertainment21 minutes agoMartin Lawrence’s Daughter, Jasmin, and Eddie Murphy’s Son, Eric Married

-

Gym & Fitness1 month ago

Gym & Fitness1 month agoBest biceps exercises with dumbbells (TRY IT, YOU'LL LIKE IT) – تمارين البايسبس

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoStock Movers: Salesforce, Southwest Airlines, Broadcom (Podcast)

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days ago2025 Indy 500: Mini-Movie | INDYCAR on FOX

-

Cryptocurrency35 minutes ago

Cryptocurrency35 minutes agoToncoin price spikes 13% amid major Telegram-related news

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoFDA commissioner looks to combat environmental toxins

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoWhy Rochelle Humes enforced a strict sex scenes ‘ban’ for husband Marvin

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoMan Utd fans turn on one player after Tottenham take lead in Europa League in comedic fashion