Crypto World

Was The 40% Rally A Retail Trap?

Uniswap price is up around 3% over the past 24 hours, trading near $3.40. But this small move hides what really happened on February 11. That day, UNI surged nearly 42% to a high near $4.57 after news linked Uniswap to BlackRock’s tokenized fund expansion.

Since then, sellers have erased about 26% of that rally. This raises a key question: was this institutional-driven breakout a real trend shift, or a trap for retail buyers?

Uniswap Price Breakout on February 11 Was Driven by Retail Momentum

The rally on February 11 did not happen randomly.

Sponsored

Sponsored

On the 12-hour chart, Uniswap price had been forming a bullish setup since mid-January. Between January 19 and February 11, UNI made lower lows while the Relative Strength Index, or RSI, made higher lows. RSI measures momentum by tracking buying and selling strength. When price falls, but RSI rises, it signals a bullish divergence, often warning that selling pressure is weakening.

Want more token insights like this? Sign up for Editor Harsh Notariya’s Daily Crypto Newsletter here.

This divergence suggested that a rebound was building.

That signal was confirmed on February 11. On that day, On-Balance Volume, or OBV, broke above a long-term descending trendline. OBV tracks whether volume is flowing into or out of an asset. When OBV breaks upward, it usually shows growing retail participation. The timing was important.

RSI divergence had been in place for weeks. OBV only broke out on February 11, exactly when the BlackRock-linked news hit the market. This shows that retail traders reacted aggressively to the headline, rushing into UNI.

Sponsored

With momentum and volume aligned, the Uniswap price surged to around $4.57 in a single session. But the structure of that candle raised early warning signs.

On the 12-hour chart, the breakout candle formed with a very long upper wick and a small body. This means buyers pushed the price higher, but sellers absorbed most of the move before the close. It was the first sign that a strong supply existed near $4.50. The rally looked powerful. But distribution had already started.

Whale Selling Near $4.57 Explains the Sharp Rejection

The long wick on February 11 was not driven by random selling. Whale data shows who was responsible.

On that day, supply held by large Uniswap holders dropped sharply from about 648.46 million UNI to 642.51 million UNI. That is a reduction of roughly 5.95 million tokens. At prices near $4.57, this represents selling pressure worth about $27 million.

This was not profit-taking by small traders. It was a coordinated distribution by large wallets.

Sponsored

Sponsored

While retail buyers were chasing the breakout, whales were exiting into strength. This explains why the UNI price failed to hold above $4.50 and why the rally collapsed so quickly. Once large holders finished selling, buy-side momentum weakened. Without whale support, the market could not sustain elevated prices.

The result was a fast retracement. From the $4.57 peak, the Uniswap price fell about 26%. Most late buyers were possibly immediately pushed into losses. This confirms that the BlackRock-related surge became a liquidity event for large holders.

Retail provided the demand. Whales provided the supply.

4-Hour Chart Shows the Uniswap Price Rally Target Was Already Completed

The lower timeframe explains why the pullback started so quickly. On the 4-hour chart, Uniswap had been forming an inverse head-and-shoulders pattern inside a descending channel. This is a classic reversal structure that often signals a short-term breakout.

Sponsored

Sponsored

On February 11, UNI broke above the neckline of this pattern and quickly reached its projected target near $4.57. In technical terms, the setup had already completed its measured move.

At the same time, the 4-hour OBV divergence became clear. Between late January and February 11, UNI moved higher, but OBV continued trending lower. This shows that volume strength was weakening even as the price rose. This bearish OBV divergence warned that the breakout was not being supported by sustained retail demand. Plus, the OBV is currently trending down, showing retail offloading.

Retail traders focused on the price move. Whales focused on the structure. By the time most buyers entered, the rally was already mature. Now, price is drifting near $3.40 while volume continues to weaken. This suggests that speculative demand is fading.

If UNI holds above $3.21, the market may attempt consolidation. But this support is fragile because it is built on short-term buying, not long-term accumulation.

A breakdown below $3.21 would likely trigger another sell wave. In that case, the next major level sits near $2.80, which marks the head of the prior reversal pattern. A move to this zone would erase all of the BlackRock-driven gains.

To regain strength, Uniswap price must reclaim the $3.68 to $3.96 region. This area now acts as a major obstacle after the failed breakout. Only a sustained move above it would reopen upside toward $4.57.

Crypto World

Will PIPPIN price crash after rallying 200% this week?

PIPPIN price has shot up nearly 200% over the past week, driven by sharp demand from futures traders. Is the meme coin set to see more gains, or will it crash?

Summary

- PIPPIN price rallied 200% over the past week, primarily driven by a spike in speculative trading.

- The meme coin has confirmed a rounded bottom pattern on the daily chart.

According to data from crypto.news, the Pippin (PIPPIN) price rallied over 200% in the past 7 days to a high of $0.52, which is roughly 7% short of breaking past its previous all-time high of $0.55 hit last month.

The PIPPIN rally appears to be mostly fueled by increased speculative activity, as traders aggressively opened bullish positions in the derivatives market, a trend common among high-volatility meme coins where momentum is often driven by leverage rather than fundamental developments.

Data from CoinGlass shows that PIPPIN futures open interest has jumped to an all-time high of $217 million, nearly four times the amount recorded nearly a week ago. At the same time, the long/short ratio stood above 1, suggesting more investors were betting on further price increases.

Open Interest reflects the total number of outstanding derivative contracts that have not been settled. When a surge in Open Interest comes along with the price rise of an asset, it indicates new money entering the market.

Meanwhile, the aggregated funding rate was positive at press time at 0.0070%, which shows that long position holders were paying fees to short sellers, conditions that help support continued upward momentum.

It should, however, be noted that PIPPIN’s rally came without the backing of any major news or development from the project’s team. Its official X account has not posted anything since August last year.

Despite this lack of official communication, the retail sentiment surrounding the token has remained bullish, as seen in CoinMarketCap.

Another point of concern is the market-wide downturn fueled by Bitcoin’s underperformance over the past trading sessions. Crypto investors are currently spooked by concerns over another U.S. government shutdown and uncertainty over Fed policy direction.

On the daily chart, PIPPIN price appears to be forming the cup of a multi-week cup and handle pattern, which has been developing since late January.

The cup and handle pattern is one of the most bullish continuation patterns that often signals an existing uptrend is likely to resume after a period of consolidation. The cup in itself is also formed of a rounded bottom pattern, which is yet another bullish indicator by itself.

At press time, the PIPPIN price had already broken above the neckline of the rounded bottom formed.

Considering this, the Solana-based meme coin could likely continue to be in an uptrend, with the path of least resistance appearing to be a bullish move to new highs around $0.89, calculated by adding the height of the rounded bottom formed to the point at which the price crossed the neckline.

Looking at technical indicators also gives us a grounded view of such a bullish forecast. Notably, the supertrend indicator has flashed green while the MACD lines have pointed upwards, both signs that bulls still have significant control over the market price action.

Unless the current upward momentum is hampered by macroeconomic headwinds, PIPPIN’s technical breakout is expected to serve as a bullish catalyst.

Disclosure: This article does not represent investment advice. The content and materials featured on this page are for educational purposes only.

Crypto World

Pentagon Pushes AI Companies to Deploy Tools on Classified Networks

TLDR

- The Pentagon is urging AI companies to make their tools available on classified networks.

- Chief Technology Officer Emil Michael highlighted AI’s role in all classification levels.

- OpenAI and Anthropic are negotiating military use of their tools with varying degrees of restriction.

- OpenAI has agreed to provide its models on unclassified networks under genai.mil.

- Anthropic has expressed concerns over military use in weapon targeting and domestic surveillance.

The Pentagon is pushing for top AI companies like OpenAI and Anthropic to make their tools available on classified networks. The military aims to expand the deployment of AI across both classified and unclassified domains. The move has sparked debate between the Pentagon and AI companies over usage restrictions.

Pentagon Aims to Deploy AI Tools on All Classification Levels

According to a Reuters report, Pentagon Chief Technology Officer Emil Michael urged tech executives to provide AI models for use on both classified and unclassified networks.

“The Pentagon is moving to deploy frontier AI capabilities across all classification levels,” a government official stated.

Currently, AI companies mainly offer their tools for unclassified networks, but this push marks a shift in the military’s strategy. The military seeks to use AI’s power to synthesize data and assist decision-making processes.

However, many AI models have built-in safeguards to prevent misuse. These safeguards have led to tension as Pentagon officials argue for fewer restrictions on deployment, saying the tools should be accessible as long as they comply with U.S. laws.

Ongoing Negotiations with AI Companies

The Pentagon has engaged in ongoing talks with leading AI firms about military applications. OpenAI recently struck a deal with the Pentagon to make its tools available on an unclassified network, known as genai.mil. As part of the agreement, OpenAI removed many restrictions but kept some safeguards in place to ensure safe usage.

While OpenAI’s agreement focuses on unclassified networks, discussions with Anthropic have been more complex. Anthropic executives have expressed concerns about using their models for weapon targeting or domestic surveillance. The company, however, is working with the Department of War to find ways to support national security missions while maintaining its guidelines.

These developments signal a shift in how AI will be integrated into the military. The Pentagon continues to explore the potential of AI tools in critical missions, despite concerns over their reliability in high-risk situations.

Crypto World

Withdrawal Freeze at BlockFills Revives Post-FTX Anxiety

BlockFills, a Chicago-based crypto lender and liquidity provider, has temporarily halted client deposits and withdrawals.

The move comes as the crypto market continues to experience notable volatility, with asset prices trending lower.

Crypto Liquidity Provider BlockFills Stops Withdrawals and Deposits During Market Stress

BlockFills operates as a cryptocurrency solutions firm and digital asset liquidity provider. It serves approximately 2,000 institutional clients, including crypto-focused hedge funds and asset managers. In 2025, the firm handled $60 billion in trading volume.

Sponsored

Sponsored

The company said in a statement posted on X that the suspension was implemented last week and remains in effect. According to BlockFills, the decision was made in light of “recent market and financial conditions” and is intended to “protect both clients and the firm.”

Despite the suspension of deposits and withdrawals, clients have continued to trade on the platform. BlockFills said users are still able to open and close positions in spot and derivatives markets, as well as select other circumstances.

The company also said management is working closely with investors and clients to resolve the situation and restore liquidity to the platform.

“The firm has also been in active dialogue with our clients throughout this process, including information sessions and an opportunity to ask questions of senior management. BlockFills is working tirelessly to bring this matter to a conclusion and will continue to regularly update our clients as developments warrant,” the statement read.

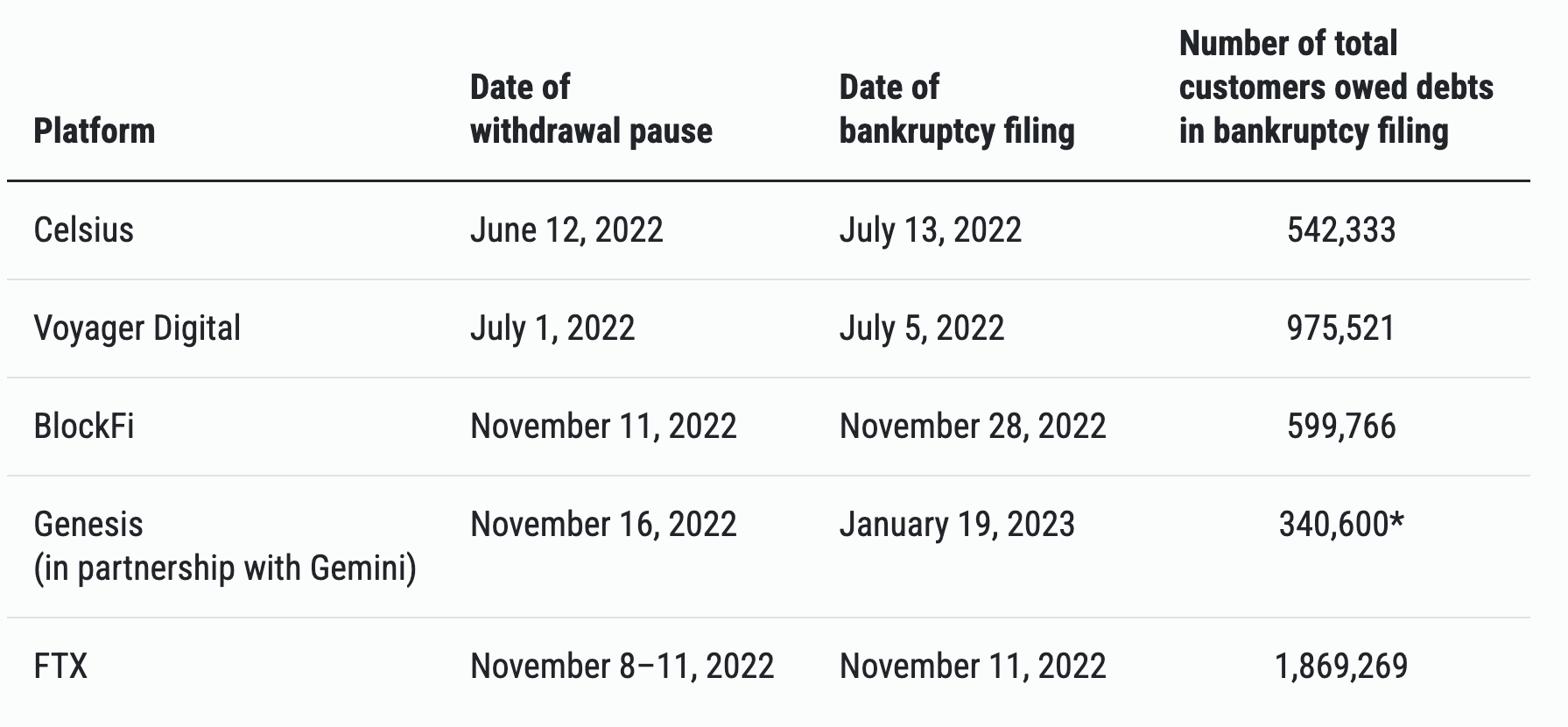

In the crypto industry, withdrawal freezes often trigger concern. The sector’s last severe downturn in 2022 saw several high-profile lenders, including Celsius, BlockFi, Voyager, FTX, and more, halt withdrawals before filing for bankruptcy.

Many of the crypto bankruptcies, such as those of FTX, BlockFi, and Three Arrows Capital, were interconnected, leading to a domino effect in the market. The events led to market destabilization and negatively impacted sentiment.

Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that temporary suspensions can also function as defensive measures during periods of intense market stress. At present, there is no publicly available evidence suggesting that BlockFills is insolvent.

Meanwhile, the suspension comes as some market participants warn of a renewed “crypto winter.” Since the start of the year, the total cryptocurrency market capitalization has declined by more than 22%.

Last Friday, Bitcoin fell to around $60,000, marking its lowest level since October 2024. The asset remains roughly 50% below its all-time high of approximately $126,000, recorded in October.

Crypto World

Will XRP Community Day trigger a rally?

XRP Community Day has put Ripple’s token back in focus as traders look for catalysts amid a fragile market structure.

Summary

- XRP Community Day has refocused attention on the XRP Ledger’s ecosystem, highlighting developer activity and community engagement rather than delivering a single market-moving announcement.

- XRP is consolidating near the $1.37–$1.38 support zone, with narrowing Bollinger Bands and a recovering CMF suggesting selling pressure is easing, though upside remains capped below $1.45–$1.50.

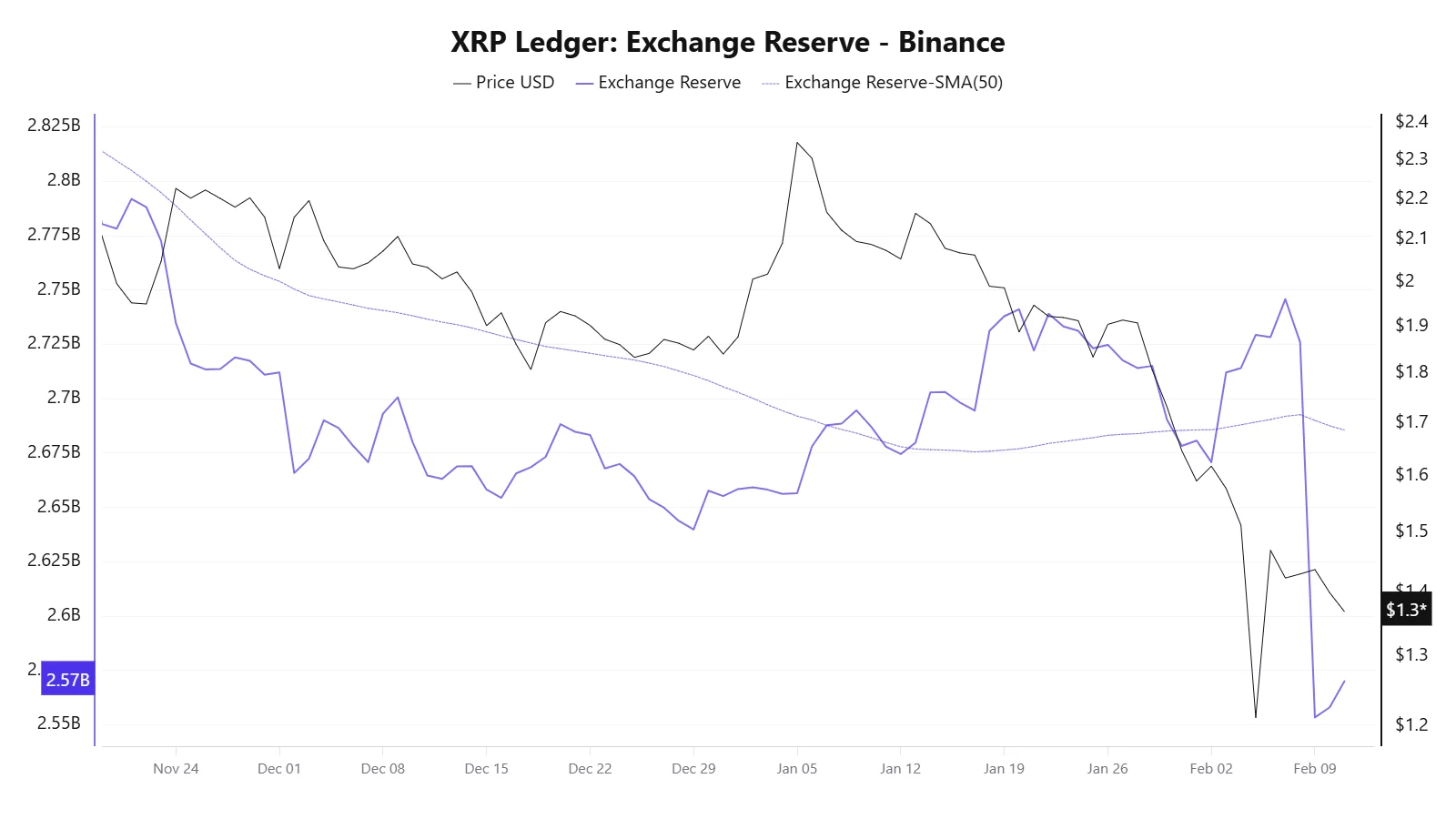

- Declining XRP exchange reserves on Binance point to reduced immediate sell-side supply, offering a supportive backdrop if renewed community-driven interest translates into demand.

The community-led event highlights ecosystem updates, developer activity, and ongoing engagement around the XRP (XRP) Ledger. This could help refocus attention on fundamentals after weeks of price weakness.

While XRP Community Day is not tied to a single market-moving announcement, it often serves as a sentiment booster, particularly during consolidation phases.

Increased visibility, renewed social engagement, and discussion around XRPL use cases can act as short-term momentum drivers if broader market conditions cooperate.

XRP price action steadies near key support

XRP is trading near the $1.37–$1.38 zone at press time, attempting to stabilize after a steady pullback from highs above $1.60 earlier this month.

The price is holding near the middle-to-lower portion of the Bollinger Bands on the daily chart. The bands have started to narrow, signaling reduced volatility following the recent sell-off.

While XRP is no longer hugging the lower Bollinger Band, indicating that downside momentum has eased, price has struggled to reclaim the mid-band (20-day moving average). As long as XRP remains below this level, upside attempts are likely to face resistance.

A sustained move above the mid-band would open the door toward the upper band near the $1.45–$1.50 zone.

The Chaikin Money Flow (CMF) remains slightly below the zero line but has turned higher from recent lows, suggesting selling pressure is fading. A move back into positive territory would signal improving capital inflows.

A failure to do so could leave XRP vulnerable to a retest of support around $1.35, followed by $1.28 on a deeper pullback.

Exchange reserve data hints at supply dynamics

Moreover, CryptoQuant data shows XRP exchange reserves on Binance have declined recently, suggesting fewer tokens are being held on exchanges.

This trend typically points to reduced immediate sell-side pressure, as more XRP moves into private wallets rather than remaining available for spot selling.

While falling exchange reserves alone do not guarantee a rally, they can provide a supportive backdrop if demand picks up. Combined with community-driven attention from XRP Community Day, the supply-side dynamics could help limit downside risk in the near term.

Overall, XRP remains in a consolidation phase, with Community Day acting as a sentiment catalyst rather than a guaranteed breakout trigger. Traders will be watching whether XRP can defend the $1.35 support zone and reclaim resistance near $1.45 to signal a shift toward recovery.

Crypto World

WTI Oil Price Climbs to a Monthly High

As the XTI/USD chart shows, the price per barrel moved above the 4 February peak yesterday, marking its highest level since the start of the month. The bullish sentiment has been driven by geopolitical uncertainty. According to media reports:

→ The Trump–Netanyahu meeting in Washington on 10–11 February failed to ease tensions. Despite Omani mediation and statements suggesting a “near compromise”, no formal agreement has yet been reached.

→ Reports of a possible deployment of additional US carrier strike groups to the Middle East have added to market nerves. Any escalation could threaten supplies through the Strait of Hormuz, which accounts for around 20% of global oil consumption.

While the fundamental backdrop remains tense and continues to support higher oil prices, the chart simultaneously points to vulnerability to a pullback.

Technical Analysis of the XTI/USD Chart

When analysing the WTI oil chart on 5 February, we:

→ used recent price swings to construct a broad ascending channel (shown in purple), noting that its lower boundary was acting as support;

→ suggested that the $65 level would become a key obstacle for bulls attempting to maintain upward momentum.

Recent price action supports this view, as:

→ if yesterday’s move above the 4 February high is treated as a bullish breakout, it appears to have failed — a potential bull trap;

→ a bearish engulfing reversal pattern has formed on the chart (indicated by the arrow).

It is noteworthy that many investment bank analysts consider current WTI prices to be overstretched, forecasting a decline towards the $57–59 range due to oversupply. However, such a scenario would likely require a reduction in geopolitical risk.

In light of the above, it is reasonable to assume that the initiative may now be shifting to the bears, who could attempt to push prices towards the lower boundary of the channel. The $64.40 level — which acted as resistance last week — now appears to offer local support.

Start trading commodity CFDs with tight spreads (additional fees may apply). Open your trading account now or learn more about trading commodity CFDs with FXOpen.

This article represents the opinion of the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand only. It is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, or recommendation with respect to products and services provided by the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand, nor is it to be considered financial advice.

Crypto World

Binance CEO Richard Teng breaks down the ‘10/10’ nightmare that rocked crypto

Binance did not cause the crypto market liquidation event on Oct. 10, but every exchange — centralized or decentralized — saw massive liquidations that day after China imposed rare earth metal controls and the U.S. announced fresh tariffs, said Binance Co-CEO Richard Teng.

About 75% of the liquidations took place around 9:00 p.m. ET, alongside two unrelated, isolated issues: a stablecoin depegging and “some slowness in terms of asset transfer,” Teng said Thursday at CoinDesk’s Consensus Hong Kong conference.

“The U.S. equity market plunged $1.5 trillion in value that day,” he said. “The U.S. equity market alone saw $150 billion of liquidation. The crypto market is much smaller. It was about $19 billion. And the liquidation on crypto happened across all the exchanges.”

Some users were affected by this, which Binance helped support, he said, an action other exchanges did not take.

Binance facilitated $34 trillion in trading volume last year, he said, with 300 million users. Trading data does not indicate any massive withdrawals from the platform.

“The data speaks for itself,” he said.

Speaking more broadly, Teng said the crypto market was tracking broader geopolitical tensions but that institutions are still pouring into the sector.

“At the macro level, I think people are still uncertain about interest rate movements going forward,” he said. “And there’s always the trend of geopolitics, tension, etc. Those weigh on these assets, such as crypto.”

However, pointing to how the sector has changed over the past four to six years, Teng said long-term industry participants will have noticed that crypto prices move cyclically.

“I think what we have to look at is the underlying development,” he said. “At this point in time, retail demand is somewhat more muted compared to the past year, but the institutional deployment, the corporate deployment is still strong.”

Institutions are still entering the sector, even despite the market, he said, “meaning the smart money is deploying.”

Crypto World

Nikkei 225 Retreats From Record High

As the chart shows, the Nikkei 225 index (Japan 225 on FXOpen) reached a historic high near 58,500 points on Monday. Bullish sentiment was driven primarily by political developments.

According to media reports, the rally followed the decisive victory of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) under Sanae Takaichi, who has signalled aggressive fiscal stimulus measures (a package exceeding $135 bn), food tax cuts, and the continuation of an accommodative monetary policy stance.

However, today the Nikkei 225 is showing signs of a pullback. It is possible that major market participants have begun taking profits amid the wave of optimism, as Takaichi’s victory had already been largely priced in, and official confirmation of a parliamentary supermajority may have acted as a trigger to close long positions.

From a technical perspective, a retracement also appears justified.

Technical Analysis of the Nikkei 225 Chart

It is worth noting that:

→ after the RSI moved into extreme overbought territory, it formed a bearish divergence with price;

→ price action itself produced a bearish triple top pattern.

As the decline unfolds, a local trendline (shown in purple) has shifted from acting as support to functioning as resistance.

In light of the above, it is reasonable to assume that an extended pullback could drive the Nikkei 225 towards the median of the long-term ascending channel.

In the event of a deeper correction, the support zone below the 56,000 level may come into play, where a previous bullish imbalance formed characteristics of a Fair Value Gap pattern.

Trade global index CFDs with zero commission and tight spreads (additional fees may apply). Open your FXOpen account now or learn more about trading index CFDs with FXOpen.

This article represents the opinion of the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand only. It is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, or recommendation with respect to products and services provided by the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand, nor is it to be considered financial advice.

Crypto World

ARK Invest Snaps Up $33M in Robinhood Shares Amid Bitcoin Dip

ARK Invest, the investment firm led by Bitcoin bull Cathie Wood, snapped up a significant batch of crypto-linked stocks on Wednesday as BTC briefly dipped below $66,000.

ARK purchased 433,806 shares of Robinhood (HOOD) for approximately $33.8 million, according to a trade notification reviewed by Cointelegraph.

The asset manager also boosted its exposure to crypto exchange Bullish (BLSH) and USDC (USDC) issuer Circle (CRCL), acquiring 364,134 shares valued at $11.6 million and 75,559 shares worth $4.4 million, respectively.

The purchases came as all three stocks traded lower on the day, with Robinhood shares sliding nearly 9%, according to TradingView data.

ARK withheld from buying more Coinbase (COIN) shares after dumping $17 million of the stock last week.

Robinhood becomes top crypto holding in ARK’s flagship fund

ARK’s latest Robinhood acquisition coincided with the company’s official testnet launch of the Robinhood Chain, a permissionless layer 2 (L2) blockchain built for financial services and tokenized real-world assets (RWAs).

Earlier this week, Robinhood reported record net revenue of nearly $1.28 billion for the fourth quarter of 2025. While revenue surged 27% year over year, it fell short of Wall Street expectations of $1.34 billion, sending the stock down about 8%.

As of Feb. 11, Robinhood stands as the largest crypto-linked position in ARK’s flagship ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK), accounting for roughly 4.1% of the portfolio, or about $248 million, according to the fund’s data.

Spot Bitcoin ETFs mirror BTC weakness as inflows stall

Broader market weakness has spilled over into US spot Bitcoin (BTC) exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which failed to sustain momentum after a three-day inflow streak.

According to SoSoValue data, Bitcoin ETFs recorded $276.3 million in net outflows on Wednesday, nearly wiping out weekly gains, which now stand at just $35.3 million. Total assets under management declined to $85.7 billion, the lowest level since early November 2024.

Ether (ETH) ETFs also posted losses, with daily outflows totaling $129.2 million. XRP (XRP) funds saw no inflows, while Solana (SOL) ETFs recorded modest inflows of roughly $0.5 million.

Related: Strategy CEO eyes more preferred stock to fund Bitcoin buys

At the time of publication, Bitcoin was trading at $67,227, up 0.4% over the past 24 hours, according to CoinGecko.

The latest pullback comes after analysts had pointed to a potential inflection point in crypto investment products following three consecutive weeks of outflows totaling more than $3 billion.

Magazine: Is China hoarding gold so yuan becomes global reserve instead of USD?

Crypto World

BNB Chain real-world assets soar 555% on institutional demand

BNB Chain’s real-world assets surged 555% in Q4 2024 as institutions tokenized funds and stocks, even as BNB’s market cap and DeFi TVL faced volatility.

Summary

- Real-world asset value on BNB Chain climbed 555% year over year in Q4 2024, making it the second-largest RWA network behind Ethereum.

- Institutional players tokenized money market funds, U.S. stocks, and ETFs via partners like CMB International, Ondo Global Markets, and Securitize.

- Despite a Q4 BNB market-cap drop and softer DeFi TVL, network activity, stablecoin supply, and infrastructure upgrades continued to strengthen.

Real-world assets on BNB Chain (BNB) expanded 555% year over year in the fourth quarter of 2024, driven by institutional capital inflows and stablecoin growth, according to a report by research firm Messari.

The blockchain network ranked second among all blockchains by real-world asset value at quarter-end, surpassing Solana and trailing only Ethereum, the report stated. The growth occurred despite a decline in the network’s native token price during the period.

BNB Chain’s native token market capitalization fell quarter over quarter following an industry-wide liquidation event on Oct. 11 that pressured cryptocurrency markets, according to Messari. The token had reached a record high in mid-October before declining through year-end. The token remained the third-largest cryptocurrency by market capitalization at quarter-end, behind Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Network activity strengthened during the quarter, with average daily transactions rising substantially from third-quarter levels, the report said. Daily active addresses also increased, with early October volatility causing a brief spike in activity. Excluding that surge, usage remained above third-quarter levels, indicating steady user growth, according to Messari.

Total real-world asset value on BNB Chain rose sharply from the third quarter and increased 555% from the prior year, the research firm reported.

Institutional partnerships drove the expansion. In October, BNB Chain partnered with CMB International to launch a tokenized money market fund. Ondo Global Markets subsequently added more than 100 tokenized U.S. stocks and exchange-traded funds to BNB Chain, expanding offerings beyond money market funds into equities. In November, a major institutional fund issued through Securitize expanded to BNB Chain, according to the report.

Real-world asset value remained concentrated in a small number of products. A single product accounted for the majority of total value, followed by another representing approximately one quarter, Messari stated. Other assets, including Matrixdock Gold and VanEck’s Treasury Fund, held smaller amounts. Tokenized shares of major companies represented a small portion of overall value.

BNB pivoting towards real-world assets

Decentralized finance activity slowed during the fourth quarter, with total value locked declining from third-quarter levels, the report said. Total value locked remained above year-earlier levels, and BNB Chain ranked as the third-largest network by that metric.

PancakeSwap remained the largest decentralized finance platform on the network, holding a significant portion of total value locked and controlling approximately one-third of the market, according to Messari. Its total value locked declined by a small amount, indicating user and fund retention. Other protocols experienced declines following liquidity withdrawals and reduced borrowing demand, with smaller projects affected most significantly as traders reduced risk exposure.

Stablecoin supply on BNB Chain increased during the quarter, with total stablecoin value rising, the report stated. One major stablecoin remained the largest after posting gains. Another prominent stablecoin grew substantially, aided by payment use cases and gas-fee discounts.

New partnerships expanded payment applications on BNB Chain. A payments network added support for multiple stablecoins to settle cross-border transfers on-chain and later enabled cloud-service customers to pay for services using BNB through the system, according to Messari. A new stablecoin launched in December allowing users to mint tokens using major stablecoins as collateral.

BNB Chain deployed several upgrades in 2024, including Pascal, Lorentz, Maxwell, and the ongoing Fermi hardfork, the report said. Block times decreased and transaction finality improved. Network capacity more than doubled, and gas fees fell sharply.

The protocol’s 2025 plans target approximately 20,000 transactions per second with sub-second finality, according to the report. The development team plans to integrate off-chain computing with on-chain verification to process additional transactions without performance degradation. Long-term development includes a trading-focused chain designed for near-instant confirmation, Messari stated.

Crypto World

Bitcoin price prediction as BTC ETFs break three-day inflow streak

Bitcoin prices traded cautiously after US-listed spot Bitcoin ETFs snapped a three-day inflow streak, adding pressure to an already fragile market structure.

Summary

- Bitcoin traded cautiously near $67,000 after US-listed spot Bitcoin ETFs ended a three-day inflow streak, flipping back to net outflows.

- ETF flow data points to waning institutional demand, reinforcing fragile market structure amid ongoing price consolidation.

- Technically, BTC remains well below its 50-day moving average, with RSI in the low-30s, keeping near-term momentum tilted to the downside.

Bitcoin price struggles as ETF momentum stalls

Bitcoin (BTC) was trading around $67,000 at press time, struggling to attract strong upside follow-through after recent attempts to stabilize.

ETF flow data shows Bitcoin spot ETFs recorded steady inflows over the previous three sessions, signaling a brief return of institutional demand as BTC attempted to stabilize near $67,000.

However, that trend reversed in the latest session, with net outflows replacing inflows, suggesting renewed caution among investors amid ongoing price consolidation.

The halt in ETF inflows comes as broader risk sentiment remains mixed, with traders closely watching whether institutional demand can reassert itself after weeks of volatility.

Bitcoin price action weak below key moving average

The daily chart shows Bitcoin remains well below its 50-day simple moving average, which is currently hovering near $85,000. This large gap highlights the depth of the recent correction and signals that the broader trend remains under bearish control.

Meanwhile, the Relative Strength Index (RSI) is holding below the neutral 50 level. It sits in the low-30s, suggesting bearish momentum is still dominant, even as selling pressure has eased compared with January’s sharp breakdown.

On the downside, immediate support sits near $66,500–$66,000, a level that has repeatedly attracted buyers in recent sessions. A decisive break below this zone could expose Bitcoin to deeper losses toward $64,000, followed by a broader psychological support area near $60,000.

On the upside, initial resistance is located around $70,000, where prior rebound attempts have stalled. Beyond that, stronger resistance emerges near $74,000–$75,000, a former support zone that now acts as a selling area.

A sustained move above these levels would be required to signal a shift in near-term momentum.

Overall, Bitcoin remains in a consolidation phase following a sharp correction, with ETF flow data and broader market sentiment likely to determine whether BTC breaks higher or resumes its downward trend in the days ahead.

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoWhy Israel is blocking foreign journalists from entering

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoJD Vance booed as Team USA enters Winter Olympics opening ceremony

-

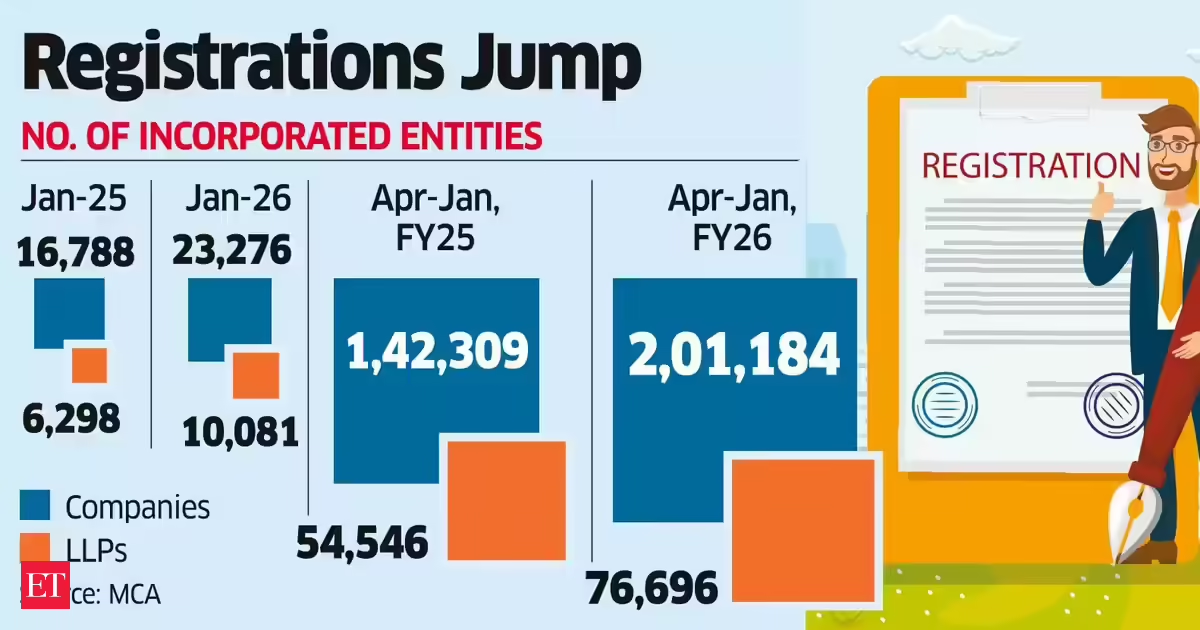

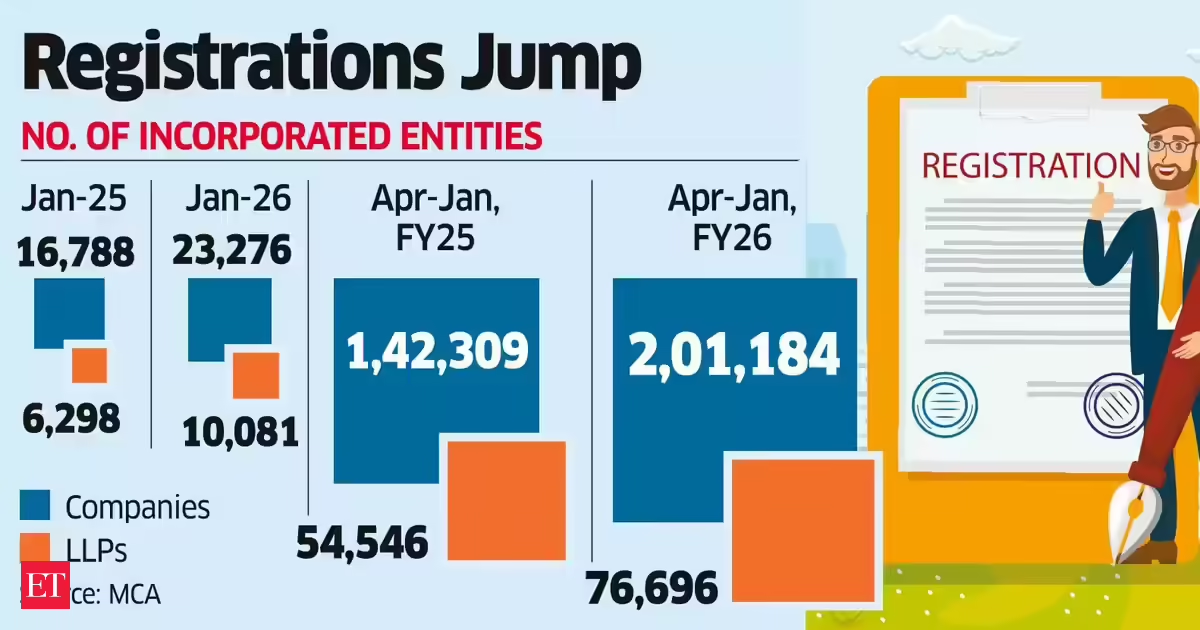

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoLLP registrations cross 10,000 mark for first time in Jan

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoMia Brookes misses out on Winter Olympics medal in snowboard big air

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoFirst multi-coronavirus vaccine enters human testing, built on UW Medicine technology

-

Sports9 hours ago

Sports9 hours agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoCostco introduces fresh batch of new bakery and frozen foods: report

-

Tech1 day ago

Tech1 day agoSpaceX’s mighty Starship rocket enters final testing for 12th flight

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoWinter Olympics 2026: Team GB’s Mia Brookes through to snowboard big air final, and curling pair beat Italy

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoBenjamin Karl strips clothes celebrating snowboard gold medal at Olympics

-

Sports5 days ago

Former Viking Enters Hall of Fame

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoThe Health Dangers Of Browning Your Food

-

Sports6 days ago

New and Huge Defender Enter Vikings’ Mock Draft Orbit

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoJulius Baer CEO calls for Swiss public register of rogue bankers to protect reputation

-

NewsBeat6 days ago

NewsBeat6 days agoSavannah Guthrie’s mother’s blood was found on porch of home, police confirm as search enters sixth day: Live

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoQuiz enters administration for third time

-

Crypto World10 hours ago

Crypto World10 hours agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Video5 hours ago

Video5 hours agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoBlockchain.com wins UK registration nearly four years after abandoning FCA process

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoU.S. BTC ETFs register back-to-back inflows for first time in a month