Entertainment

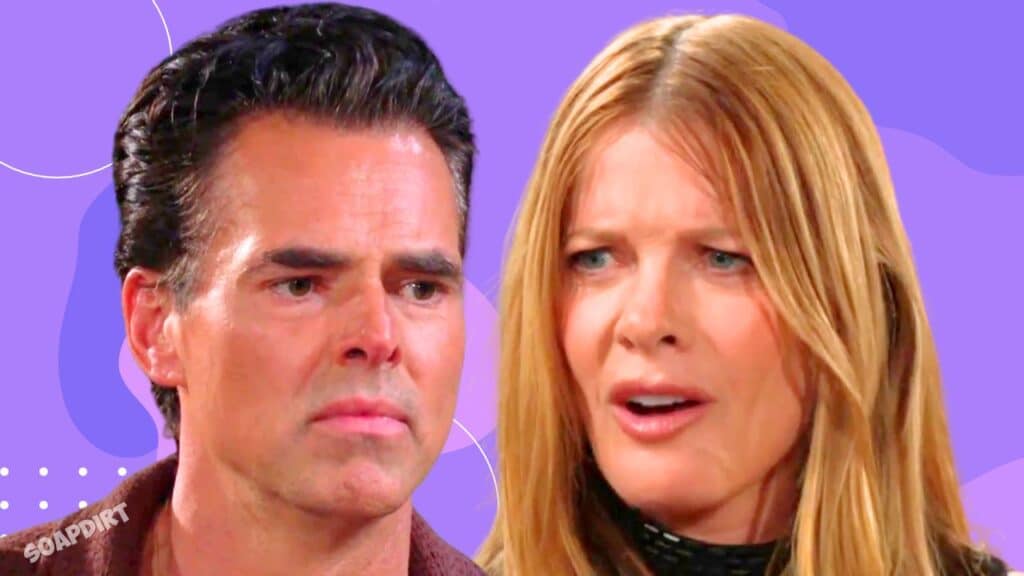

Young and the Restless: Billy & Phyllis Cross the Point of No Return – Both Lives in Ruins

Young and the Restless indicates Billy Abbott (Jason Thompson) and Phyllis Summers (Michelle Stafford) are so deep into their need for revenge and power that they have alienated everybody and are ruining their lives. Let’s talk about how there’s no coming back at this point for Billy and Phyllis.

Soon, they’re going to be left with nobody but each other, which is kind of a dismal thought. So, Billy’s feeling pretty good because he’s got Chancellor, and Newman Media under the AbbottCom umbrella. He finally got revenge on Victor Newman (Eric Braeden), but that’s about the only thing Billy got going for him because this week, his relationships fall apart.

Billy Abbott’s Revenge Backfires as Relationships Crumble on Young and the Restless

Jack Abbott (Peter Bergman) and Billy are at odds. While talking to Jack, we’re going to see Billy accusing Jack of being mad that he got the best of Victor. Billy did it, not Jack. Then, his big brother messes up Billy’s plans somehow. Maybe he gets Jill Abbott (Jess Walton) involved or makes some other move.

Things get worse for Billy when Sally Spectra (Courtney Hope) hits her breaking point. Billy was just ranting that she didn’t have ambition, and he walked out on their Valentine’s Day dinner. After a talk with her ex, Adam Newman (Mark Grossman), we’re going to see Sally head over to Billy’s place. She tells him she’s packing and she’s going.

Sally says that Billy keeps lying and saying he wants her, but what he really wants is Chancellor and revenge. Despite Sally ready to walk out on him, Billy is still trying to defend his actions. It’s crazy. He’s still saying it’s not wrong to chase his dreams, as if he wants an Olympic medal or to learn to play the piano. It’s not that. His dreams are all about revenge and Victor.

Sally Spectra Dumps Billy as Victoria Newman Plots Punishment on Y&R

Sally tells Billy he’s blinded. They’re over. They’re done. She’s out of there. Of course, he’s asking Sally, “Don’t do this.” But she tells Billy, “You’re the one that did this.” Sally says there’s no coming back from it. Billy tries saying he loves her. Sally says she loves him, too, but that Billy doesn’t think Sally is enough for him because he’s still chasing all these other terrible things.

Billy is officially dumped. He’s got nothing and nobody at this point except Chancellor. On top of that, Victoria Newman (Amelia Heinle) is plotting against Billy. She wants him punished, and she’s going to use their kids to do it. Victoria may refuse to let Billy see the kids. She may take him to court if she has to. She’s already said she’s going to tell the kids these awful things he’s done.

Victor Newman Gaslights Cane Ashby to Reclaim Newman Assets on Young and the Restless

Then we’ve got Phyllis. She betrayed Cane Ashby (Billy Flynn), and Victor now has Cane spun up into thinking that he’s going to hurt Lily Winters (Christel Khalil) and the kids unless Cane finds a way to get all the Newman assets back from Phyllis. Victor has really messed with Cane’s mind. At this point, he’s just simple. I don’t know why he isn’t taking what Victor says with a grain of salt.

Cane is supposed to be this brilliant person. He is going to try and take down Phyllis and do what Victor is demanding to save Lily and the kids because Victor has gaslit him. Cane is going to go to Daniel Romalotti (Michael Graziadei) and ask him to help stop Phyllis. Daniel is probably going to do it. We know that he hates what his mom has done and thinks Phyllis has just gone too far.

Daniel may help Cane trick Phyllis and find a way to take it back. Daniel’s had enough. Summer Newman (Allison Lanier) had enough. They’re sick of Phyllis making one awful decision after another. It’s even worse because, let’s be honest, Phyllis already hit rock bottom a couple of years ago when she faked her death back in the Jeremy Stark (James Hyde) days.

Phyllis Summers Hits Rock Bottom as Daniel and Summer Walk Away

Everybody turned their back on her then. It took a while, but eventually, Daniel and Summer forgave her. You’d think after that rock bottom, Phyllis wouldn’t keep pulling these stunts and risk losing her kids again. Apparently, she didn’t learn her lesson. Phyllis has gone to rock bottom and then she started digging, trying to find a lower point.

Daniel and Summer may finally wash their hands of Phyllis once and for all. Honestly, if Daniel conspires with Cane to get Newman Enterprises away from her, Phyllis may lash out at Daniel for betraying her. I don’t think she’d let it slide. I think she might play the victim card and say that she was done dirty.

Nick Newman and Sharon Newman Vow to Make Phyllis Pay for Her Betrayal on Y&R

Nick Newman (Joshua Morrow) and Sharon Newman (Sharon Case) also both despise Phyllis now. She has pushed them past their breaking point. Sharon said, “Everybody always forgives Phyllis, but not this time.” Nick has vowed to make Phyllis pay, and he said for the rest of her life. We all know Nick’s always a hothead, but right now the pain pill addiction and the pain are both making him more aggressive and vengeful.

He’s been annoyed with Phyllis since back when they were in France and she was looking to team up with Dumas. That was right around the time they found out it was Cane. Nick may really be done with her now. Phyllis literally has nobody who can stand to be in the same room with her except Billy.

A Billy and Phyllis Reunion on Young and the Restless? The Last Two Stand Alone

Those two don’t even get along, but by the end of this week, Phyllis and Billy are going to be the only ones that each other has left in their lives. I think everybody else is going to be done with them. Phyllis and Billy might hook up. That would ice the awful cake, right? Phyllis and Billy were in love at one point, so it wouldn’t be unprecedented.

Sally just walked out on him, and Phyllis’s bed buddy, Cane, has turned on her. If Billy slid into the sheets with Phyllis, I think that Sally would absolutely never let that go. Any chance of reconciliation would be over if Billy sleeps with Phyllis. As for Red, she’s got nothing left to lose. Why not replay her past with Billy? She’d probably be all for it.

I actually liked them together. They were engaged and they were happy at one point. They lived together and were playing video games. Then, of course, Billy slept with Summer. That was awkward. A while back, when Billy first got with Sally, we saw Phyllis having this dream about reuniting with Billy.

Young and the Restless Spoilers: Will Victor Newman Stay on the Losing Side?

That dream happened right before Phyllis and Sharon were abducted by psycho Martin Laurent (Christopher Cousins) and held captive in that creepy abandoned psych hospital. It looked for a minute like they were hinting that Billy and Phyllis may reunite, but nothing ever came of it and he moved on with Sally. Maybe we are circling back around to it.

The big question is, of course, can Billy and Phyllis hang on to what they stole? I would hope she has everything locked down with super secret, extra secure passwords. Even if Cane gets Daniel to steal Phyllis’s laptop, they shouldn’t be able to get into it. I know that a bunch of Young and the Restless fans, even those that don’t like Phyllis and Cane, want to see Victor suffer for a while before he gets his companies back.

Victor Newman to Blame on Y&R

Victor says to Adam and Nikki Newman (Melody Thomas Scott) this week, “I know you probably blame me.” They’re both like, “No, we don’t blame you.” Ridiculous. It is 100% his fault. But I guess they’re not going to go there because Josh Griffith loves Victor Newman. We’ve got a week of sweeps left, and I just really hope that we come out of it with Victor still on the losing side of this.

He needs to pay for a while longer. I do hope that, at least in terms of their corporate assets, Phyllis and Billy keep winning for a little while longer. By the end of the week, though, it looks like Phyllis’s and Billy’s personal lives are ruined. Phyllis’s kids vow they’re done, even though she thinks they’ll come around. Billy’s kids are going to find out the things he’s done. Sally walked out on Billy. Honestly, I think she should have done it months ago.

This week is critical and life-changing for the two of them. What I really hope is someone gives Cane a reality check and tells him, “Look, Victor is lying to you. You’re being played.” Phyllis told Cane that Victor was bluffing, but he didn’t believe her. Maybe Cane will speak to Jack or somebody else who has a lick of sense and knows that this Lily kidnapping is fake. Maybe Cane will snap out of it and won’t help Victor get his stuff back.

Entertainment

Legendary Western Icon Gets an Ambitious Sci-Fi Makeover in New Netflix Series

In 2023, western television tycoon Taylor Sheridan turned his attention away from the fictional Dutton family of Yellowstone and 1883 to tackle a real Lawman. Specifically, he explored one of the first African American Deputy U.S. Marshals west of the Mississippi — the legendary Bass Reeves — with the aptly named Lawmen: Bass Reeves at Paramount+. Created by Chad Feehan with Sheridan as an executive producer, the series followed the exploits of Reeves, played by David Oyelowo, as he forged his legacy as a former slave who rose to become one of the greatest heroes of the Old West. By all means, it was a success, earning rave reviews from critics and audiences alike and garnering a Critics’ Choice Award and Golden Globe nomination for Oyelowo.

Now, Netflix is taking a stab at the frontier icon, though not in a way anyone could’ve expected. Instead of going for a more historical angle like Feehan’s series, the streaming service’s new series takes place in an alternate reality Steampunk West, where it’s not just outlaws that are terrorizing people, but also machines and supernatural horrors that only a truly legendary lawman can tackle. Titled Bass X Machina, it’s the latest addition to the platform’s ever-growing slate of adult animation, promising plenty of action as Bass plays judge, jury, and executioner to the greatest threats to his family on the frontier. With every bit of justice he dispenses, however, he may end up jeopardizing the lives of everyone he’s fighting to save.

Bass X Machina was announced with two images that give a preview of this hardened version of Bass, who’s dressed every bit like the lawman he’s based on, save for having a mechanical right arm. The shots establish a world even harsher than the West that so many throughout history braved to start a new life, where even such powerful figures known for their heroism in reality are far from untouchable. Alongside the first look, Spider-Verse and Bullet Train favorite Brian Tyree Henry was tapped to voice this new version of Bass and serve as an executive producer. Henry has been killing it in animation for a while now, whether as Miles Morales’ father, Jefferson Davis, or as a young Megatron in the acclaimed Transformers One, and he’s also surrounded by a killer cast for the new series, including Janelle Monáe as Glory, Tati Gabrielle as Dana, Cree Summer as Ahni, Chaske Spencer as Lighthorse, Currie Graham as Rivenbark, and Starletta DuPois as Etta.

When Will ‘Bass X Machina’ Release?

Animation for Bass X Reeves is being done by South Korea’s Studio Mir, which previously worked on other Netflix animated hits like Devil May Cry and Skull Island. The series hails from a team including executive producers LeSean Thomas, Jennifer Wiley-Moxley, and Chad Handley, in addition to Henry. Monáe is also bringing some musical talent along with her, with Roman GianArthur and Nate Wonder from her Wondaland Arts Collective creating original music for the series. The wait to see this wild twist on such a familiar lawman won’t be overly long, as Netflix confirmed it’s due to release on the platform on October 6.

Stay tuned here at Collider for more on Bass X Machina as its release draws nearer. Check out the first images in the gallery above.

Entertainment

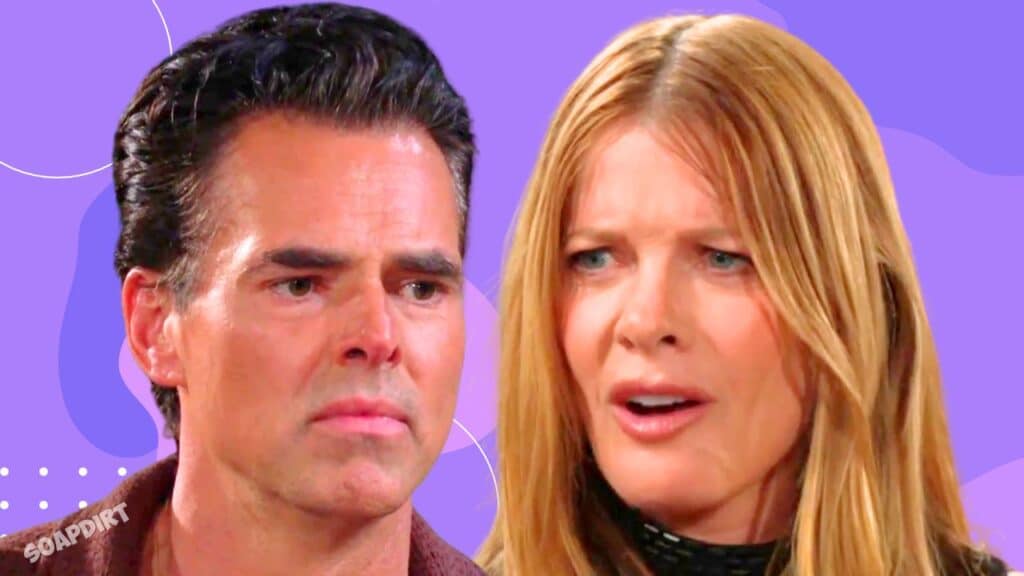

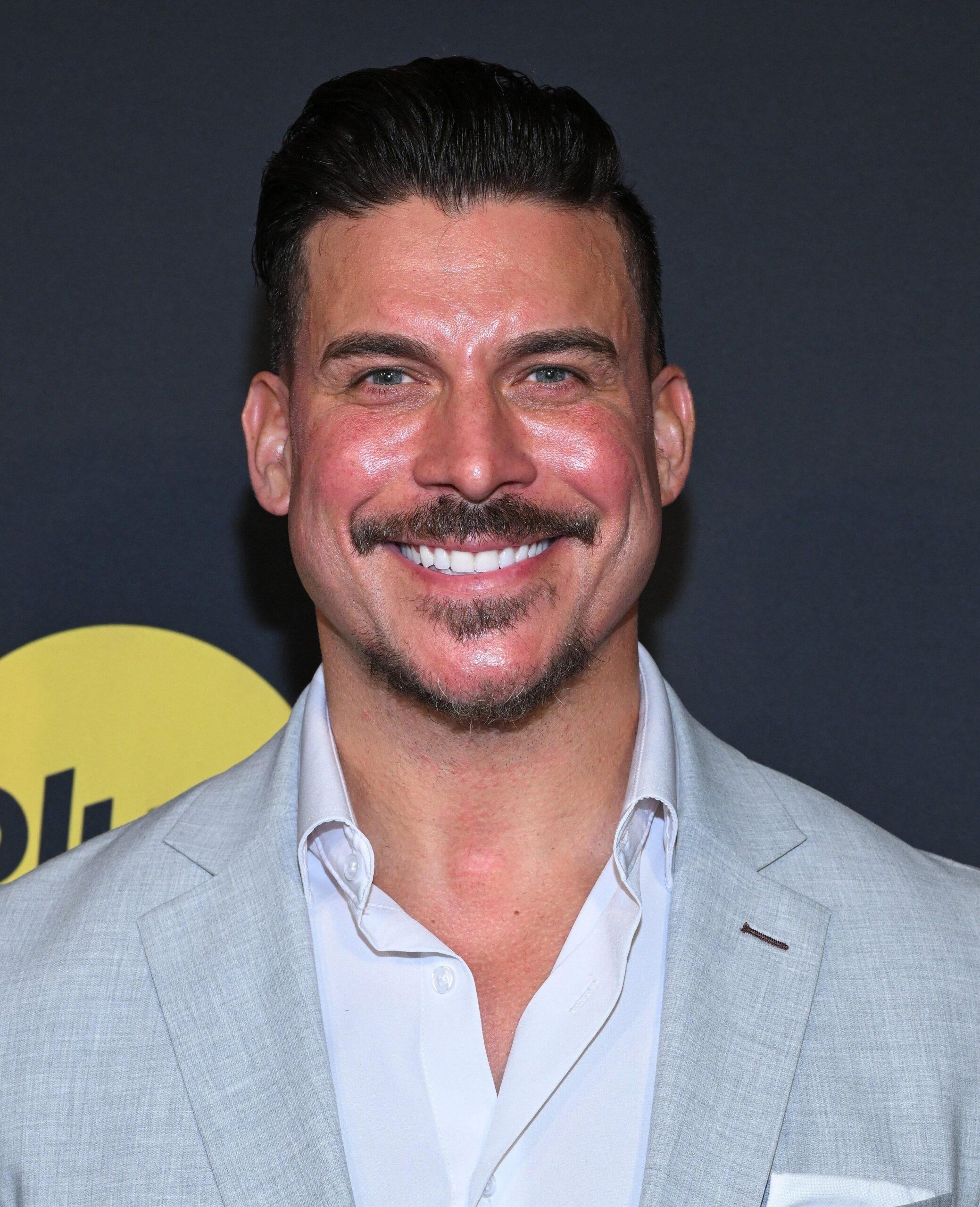

‘Valley’ Alum Jax Taylor Has Been Sober For Over A Year

Jax Taylor is one of the most talked-about alums from Bravo’s “Vanderpump Rules,” having been on the show for eight seasons until 2020. Following a hiatus, the network selected him to be a part of the cast of the “VPR” spin-off series, “The Valley.” However, near the end of the show’s second season, he announced he would not be returning, leading many fans to assume he had been fired. Now, a new report says the controversial reality star has turned his life around amid his divorce from Brittany Cartwright.

Article continues below advertisement

A New Report Says ‘Valley’ Alum Jax Taylor Is Doing Really Well

“The Valley” premiered on Bravo in March 2024, with Taylor and Cartwright among the cast. The show garnered considerable buzz, however, many agree that it became too dark in its second season, partly because of Taylor. Now, several months after announcing that he wouldn’t be on season three, an insider has told US Weekly that things are looking up for the father of one.

The source said, “He’s doing really well. Jax has been sober now for over one year and 3 months. He had even stopped smoking weed, and it’s been six months.” The insider has stated that he has since relocated to a new home but remains near Cartwright and their young son.

Article continues below advertisement

They also stated that he has “completely transformed his life,” noting, “He doesn’t go out and is very intentional with who he spends his time with. [He] lives a very quiet life and spends a lot of his time with Cruz [his son] and close friends that are on a similar path.” The insider added that the “Valley” alum is “the healthiest he’s ever been” and that others in his circle have noticed the positive changes.

Article continues below advertisement

The Former Bravo Star Recently Confirmed His Move

Taylor reportedly moved out of the home he shared with Cartwright in August 2024. However, as the insider noted to US Weekly, the former “Vanderpump Rules” star recently moved again. He confirmed the news on Instagram in February 2026, posting a video of the move and highlighting the company he used for assistance.

Taylor said in the caption of the post, “New chapter. Grateful to @roadwaymoving for making this move smooth and stress-free from start to finish. Here’s to new beginnings.”

Article continues below advertisement

Fans Are Happy To See Taylor On Social Media Again

Fans reacted not only to the move but also to seeing Taylor active on social media again. One person said, “I’m so happy to see you posting again, been wondering how you’re doing.” Someone else wrote, “Bro looks so healthy! After carrying reality TV for the past decade, he deserves to have people carry his furniture.”

Another person said, “Jax, I need to see you on ‘Traitors’! I’ve missed the number one guy in the group on my tv.” Someone else wished him luck, saying, “As you pack up this chapter and begin another, I hope you feel surrounded by strength and reassurance. Stay strong. Sometimes the most beautiful things come after the hardest transitions. Good luck!”

Article continues below advertisement

Finally, another fan said, “Good luck @mrjaxtaylor in this new chapter, rooting for you & your boy & Brittany that everything is going well as coparents.”

The Reality Star Announced His Exit From ‘The Valley’ In 2025

Season two of “The Valley” concluded in August 2025, however, in July, ahead of the finale and reunion, Taylor announced he would not be returning for the show’s third season. Per Bravo, he said in a statement, “After an incredibly challenging year and many honest conversations with my team and producers, I’ll be stepping away from the next season of The Valley.”

He added, “Right now, my focus needs to be on my sobriety, my mental health, and coparenting. Taking this time is necessary for me to become the best version of myself – especially for our son, Cruz.” This came after fans of the show called for his removal, including with a Change.org petition.

Since then, the cast has filmed the show’s third season, and it is expected to air in 2026.

Article continues below advertisement

Brittany Cartright Recently Gave A Coparenting Update

Cartwright filed for divorce from Taylor in August 2024. Since then, she has been open about the challenges of coparenting with her estranged husband. However, according to Bravo, she recently gave a more positive update while on the “California Live” podcast.

The “Valley” star said about motherhood, “I feel like I’m thriving as a single mom. My son is so amazing, and I feel like … I always wanted to be a mom. He’s so cute. He is my little everything; he’s my best friend, and, you know, honestly, I just love having him with me all the time. I just love it.”

She also noted that, despite ups and downs in coparenting with Taylor, “I think that we are getting better at it.” Cartwright added, “I take care of pretty much everything by myself, so, you know, [Jax] is doing better and a lot of things like that. He definitely loves his son, but, you know, I just get things done.”

Entertainment

Hannah Polskin Shares Why Pink, Gwyneth Paltrow, and More Celebs Are Filling Their Homes With Her Livable Art

Home is where the art is! MTV Cribs may be off the air, but one thing you’ll find in celebrity homes today is Hannah Polskin’s livable art.

From paintings and sculptures to murals and functional décor, the artist’s freeform creations bring texture, peace, and personality into stars’ everyday spaces.

Among those collecting her work: Pink, Gwyneth Paltrow, Amy Schumer, Chlöe Bailey, and Emmanuelle Chriqui.

“I’ve been making art for as long as I can remember. … My mom would tell you I’ve been drawing these shapes since I was little. …They come from an intuitive place rather than a thought-out plan. … I tend to fall in love with certain loops and curves, and I’ll revisit them over and over again,” she tells ET.

Blending fine art and design, Polskin works with wood and stone to make pieces that spark a response the moment someone enters a room.

“These aren’t just decorative objects; they’re vessels for feeling. … The undulating shapes emit the same kind of grounding energy that resonates with people. … I love when a place feels edited, but warm. … I’m always chasing calmness,” the Los Angeles, California based designer explains.

For Polskin, this means weaving creativity into everyday life with art that isn’t just reserved for a gallery wall.

“My pieces are designed to feel like they’ve always belonged there. … So much of my work comes from what I personally want to live with at home, and everything is cohesive,” the Savannah College of Art and Design alum says.

Her must-haves? “I love the idea of adding an artistic ritual around a banal activity. … Get a glimpse at your reflection in one of my full-length mirrors as you’re coming and going or use my Tissue Sculpture to dispense tissues through a giant wooden egg before blowing your nose.”

And when it comes to advice for aspiring artists and collectors alike, Polskin keeps it simple: follow instinct over perfection.

“I find my art comes out best when I let my hand roam freely and don’t attach an expectation. … I’m deeply inspired by curves, negative space, weight, and balance. … I’ll have sketching sessions in the midst of leftover scraps of wood, and it really opens my mind up when I’m starting something new.”

She recommends, “Pluck that thing from inside your head, get it out into the world, and don’t worry about the rest. … It’s important you really love the work, especially if you’re the one who will be looking at it every day. … The best collections feel personal.”

RELATED CONTENT:

Entertainment

Bold and the Beautiful: Ridge’s Interference Backfires – Forces Eric to Walk Away!?

Bold and the Beautiful has Ridge Forrester (Thorsten Kaye) finding out Eric Forrester‘s (John McCook) big secret this week. And when he does, Ridge is going to explode.

Let’s talk about how they’re going to probably force Eric to quit designing for Katie Logan (Heather Tom) at Logan.

Tension Rises at Logan as Eric Forrester Faces Production Delays on Bold and the Beautiful

This week there’s just a perfect storm of bad circumstances. Bill Spencer (Don Diamont) and Katie are talking with Eric about when the collection is going to be ready. He doesn’t want to be rushed and tells Bill and Katie that perfection takes time. Katie gets that because she’s worked at Forrester and understands it, but Bill is not a patient guy.

There’s some debate over the materials and Eric is not happy. Bill had to remind him they can’t use the same suppliers that Forrester Creations uses, even though those are better fabrics, because that would risk the big secret about Eric being the designer at Logan going public.

Bill said he had to make an executive decision. Katie was pressing Eric, saying they need some idea of when they can launch, but at the same time, she says she’ll do whatever she can to support him. Bill says he wants to be respectful of Eric, but he’s also pushing to launch Logan as fast as possible.

Eric’s Revenge Against Ridge Drives the New Logan Collection on B&B

Eric didn’t like the way the designs looked on the models. He said it’s all wrong and the work is shoddy. He wants everything to be perfect, but Bill snapped and said they can’t keep delaying the launch.

Eric clapped back, insisting he won’t do this if it can’t be done right. He’s very wrapped up in making this collection better than Forrester. Eric wants to show Ridge up because he forced Eric out.

Ridge Forrester Questions Eric’s Mysterious Stress Levels on Bold

Meanwhile, Ridge was over at Forrester telling Brooke Logan (Katherine Kelly Lang) that the doctor he and Eric share is worried about his dad’s stress levels. Of course, Ridge is wondering how Eric is stressed out. He thinks he’s retired and playing pickleball.

Ridge thinks that Eric is enjoying being retired and hanging out with Donna Logan (Jennifer Gareis), not doing anything stressful. Here’s what I wonder: why is Eric’s doctor breaking the law and blabbing about his private health matters to Ridge? That’s not okay—not one little bit.

Donna Logan Struggles to Keep Eric’s Secret from Ridge

Donna showed up over at Forrester Creations and Ridge asked why Eric is so stressed. And Donna is nervous and covers, saying Eric misses being at Forrester, which is true enough. She said he’s just trying to start a different future.

Ridge wondered what that meant because it was cryptic. Donna was hustling out of there because she didn’t want Ridge to lob any more questions she had to dodge. She headed over to Logan, where Eric was telling her how bad his first look was at the dresses that came out of production.

Bold and the Beautiful: The Deadly Physical Toll of Eric Forrester’s Fashion Startup

Once Donna was alone with Eric, she started telling him she’s really worried about all the stress he is under. Donna wants to know if the job is getting to him. It kind of is, but I think he also feels obligated.

Meanwhile, Katie was telling Bill she doesn’t want to push Eric, but Bill says they have to get this launch done. Katie thinks that keeping the secret from the family is a bad idea because it’s just very stressful on Eric, and we can see that happening on Bold and the Beautiful.

Donna and Eric left Logan and headed home. Donna brought up the doctor’s concerns about his stress levels, and Eric shares my opinion about this. He’s upset that his doctor violated his HIPAA privacy, but Donna kind of brushed it off and was going on about his health.

Ridge and Brooke Discover the Truth About Logan Designs on B&B

Donna’s worried about what working for Katie and Bill could do to Eric. She thinks it’s too much. Eric admits he does not like working with Bill and can’t stand it. But there’s also a lot of ego at play because Eric doesn’t want Ridge to think he was right to kick him to the curb.

Eric admits he is overwhelmed and would be happier if he was still at Forrester. He’s working at a startup, which is stressful, versus an established company where everybody bows down to him.

Donna tells Eric she wants him to quit Logan. Later this week, Ridge and Brooke find out that Eric is the lead designer for Logan. It’s actually Katie and Bill who tell them.

Medical Emergency on Bold and the Beautiful: Eric Collapses During Heated Ridge Confrontation

I’m betting that Katie and Bill spill primarily because Katie’s concerned about Eric, especially because he has breathing problems on Tuesday. Donna wants him to go to the hospital. We know Ridge is going to be seething when he finds out that Eric is working for Katie and Bill.

From there, there’s really only two paths to take. First, because of his anger at Ridge and because he wants to teach his son a lesson, Eric may decide to press on and keep working for Katie despite the health issues. By the end of this week, Eric is raging at Ridge, saying that Ridge is trying to take this away from him.

Will Deke Sharpe Join Logan to Save Eric’s Last Collection?

Katie could come up with a way to give Eric what he wants: to keep designing with less risk. She could bring Deke Sharpe (Harrison Cone) in and help Eric complete what’s probably his very last collection, and then Logan gets its fashion show. That way Katie can launch and Eric can have his big last design hurrah.

The other way this could go: Ridge puts down his foot like he loves to do, thinking he’s in charge of everybody. He may demand that Eric quit Logan. I expect Ridge to rage at Bill and Katie and claim they’re trying to kill his dad. I think he’ll go all out trying to force Eric to stop.

The Future of Logan Designs on B&B: Rivalry or Ruin for Katie Logan?

Things are going to get worse because when Eric is arguing with Ridge, there’s another incident and Eric’s health gets a lot worse. He’s going to collapse, struggling to breathe. Ridge is calling out to somebody to dial 911.

After this incident, I feel certain that Ridge is going to try to force Eric to quit Logan. A lot of other people will back Ridge up on that. Not only will he demand Eric quit for his health, but I think Brooke’s going to back up her husband, and Donna is also going to take their side because she doesn’t want to lose Eric.

By the end of this week, Ridge and Brooke get a confession from Eric. He wanted to do this one last collection at Forrester, but then Ridge shoved him out and wouldn’t even look at his designs. The big question now is whether Logan Designs can survive this crisis. If Eric steps away, then Katie’s got no designer and her company could be dead in the water—which she would still prefer over Eric working himself to death.

Bold and the Beautiful Spoilers: Can Brad Bell Deliver the Drama?

Ridge has been low-key hoping that Katie was going to fail. He kept saying she was in over her head. In addition to being concerned about Eric, I am quite certain Ridge would happily sabotage Logan because he despises Bill.

If Katie’s company is dead by the end of February sweeps, I’m going to be a little frustrated because they built it up as this big rivalry and that hasn’t happened. It’s very typical of Brad Bell’s writing to build up to something dramatic and then it poops out. I hope Katie gets her launch.

Entertainment

Kristin Cavallari Revisits Divorce ‘Pain’ After Revealing Dating Preference

Kristin Cavallari reflects on her feelings post-divorce, digging into her emotional side.

The media personality got candid, sharing her story and highlighting her experience after she and her now ex-husband pulled the plug on their almost seven-year marriage. Revealing the takeaways from that phase of her life, she looks back on the heartache that accompanied her growth.

Kristin Cavallari was married to former professional footballer Jay Cutler. They met in 2010, tied the knot in 2013, and remained together till 2020. The couple shares three kids: sons Jaxon and Camden, and a daughter, Saylor.

Article continues below advertisement

Kristin Cavallari Shares Lessons From Her Divorce

Cavallari recently opened up about her experience during her divorce from Cutler a few years ago. She shared that there were a handful of lessons the experience taught her, although it was painful, noting that she learned to stop being a control freak.

The media personality shared that she has come to realize that going through hard times is necessary because they help one appreciate the good times.

Stressing that there is indeed beauty in pain, she recounted when she tried to shut off her feelings. “I didn’t wanna feel anything. I wanted to push everything away. I was like, ‘I’m fine, I’m fine, I’m fine. I’m the tough girl,” she said.

Article continues below advertisement

She detailed her experience on a recent episode of her “Let’s Be Honest” podcast, disclosing that at that time, she did not know how to ask for help or feel vulnerable. Cavallari said she allowed herself to go through the emotional roller coaster and live through the pain, not run from it.

“And thank God I did, because that was where the majority of my growth and life came from. The pain, and the hurt, and the suffering are there to teach us something,” the podcaster added.

Article continues below advertisement

The Media Personality Shared That Her Divorce Fueled Growth

The podcaster continued, stating that trying to run from pain was a disservice to oneself, as beauty lies at the end of the path. Last year, she spoke to US Weekly, revealing the growth she had experienced after the divorce, which was finalized in 2022.

She said that the years spent apart from her ex-husband have been instrumental in her growth as a person.

“I think growing up and realizing that what I had done previously wasn’t working for me and I needed to figure out what needed to change to set up the second half of my life to be really peaceful,” Cavallari revealed.

The former lovers spent about a decade together as they met in 2010 but got married in 2013, a year after their eldest son, Camden, was born. Ultimately, they decided to call it quits in 2020.

Article continues below advertisement

The Mother-Of-Three Revealed A New Requirement On Her Dating List

Cavallari previously got candid about her getting back into the dating pool, sharing what she now considers a red flag in a man.

She noted that a man without kids or the desire to have some is a no-go for her, and this made the list due to her experiences as a mother. “Someone who doesn’t have kids and doesn’t want any, I’m like, ‘You won’t understand my life,’” the mom of three explained.

As shared by The Blast, Cavallari gave insight into her line of reasoning, stressing that motherhood broadens a woman’s emotional perspective, and a potential partner without children might find it hard to relate, thereby causing friction in the relationship.

Article continues below advertisement

The ‘Laguna Beach’ Alum Wants Nothing To Do With Insecure Men

Cavallari’s list of preferences grows longer as she gets into dating head-on. In addition to men without kids, the podcaster has some career preferences too. She shared previously that she does not want men in the acting niche because she views them as generally insecure.

She described actors as a “bunch of nerds,” explaining that in her opinion, they usually lacked confidence, hence they were not her type. “Typically, actors are very insecure, and I think that’s why they become actors, because they’re seeking outside validation,” the media personality noted.

The podcast host disclosed that another reason she was not into actors was that she had no interest in having a long-distance relationship. Busy schedules and frequent traveling were a red zone in her books.

The Blast reported that even though the acting career was a major turnoff for her, she still found some actors, like Brandon Sklenar, physically appealing.

Article continues below advertisement

Kristin Cavallari Claimed She Walked Out Of Her Marriage Without A Penny From Her Ex

The mom of three made headlines and fueled beef with her ex-husband when she publicly declared that her divorce with the former NFL player did not yield any monetary settlement.

While discussing the creation of her company Uncommon James, which she launched in 2017, she said, “I have never gotten a penny from my ex-husband, I didn’t get any money from our divorce, so let’s just clear that up. Thank you.”

Cavallari also debunked the rumors that her success with her lifestyle brand was funded by Cutler’s NFL earnings, explaining that she received no external funding.

Cutler rained heat on the “Laguna Beach” alum for her statement, tagging it completely false, “It’s insanity. It’s completely false, completely untrue,” the former NFL star said.

He also stressed that the company was a marital asset and that Cavallari got a good sum following their divorce, as shared by The Blast.

Entertainment

Netflix Has An Unrated Comedy That Makes Funerals Funny

By Robert Scucci

| Published

Normally, I’m perfectly okay when a Jay Baruchel vehicle gets tanked by critics because there’s something about the characters he portrays that irritates me to no end. After watching 2007’s Just Buried, I had a similar revelation about him that I recently had about Justin Long. Justin Long is often typecast as a jerk because he’s so good at playing that guy. Similarly, Jay Baruchel has an innate ability to play a hapless wiener who you just want to give a swirlie.

I know my thinking is wrong here because actors like Baruchel and Long get typecast in these roles precisely because they’re exceptionally good at them. The reason I don’t like their characters is because they’re not supposed to be likable. This isn’t an indictment of who they are as real people, but a celebration of the talent they bring to the table and how well it works when applied correctly.

Though Just Buried’s 33 percent critical score on Rotten Tomatoes would lead you to believe this isn’t one of Jay Baruchel’s finer hours, I’m going to respectfully disagree. It’s one of the few movies where he gets top billing (2013’s This is the End being the other one) that I’d actually recommend to anybody curious about what he has to offer.

A Deadly Inheritance

Jay Baruchel’s Oliver Whynacht (pronounced “why not”) is more charming in Just Buried than the critics would have you think. Summoned to a small town in Nova Scotia for his father Rollie’s (Jeremy Akerman) funeral, Oliver, a grocery store delivery boy with no real prospects on the horizon, is shocked to learn he’s inherited his entire estate, including the struggling funeral home Rollie owned and operated. What Oliver doesn’t realize is that the business is facing bankruptcy because rival owner Wayne Snarr (Christopher Shore) has been poaching all of his potential clients from the nearby retirement home.

Rollie’s widow, Roberta (Rose Byrne), who works as the embalmer, quickly befriends Oliver, and the two hit it off. Their budding friendship is tested when Oliver, who gets a nosebleed whenever he’s stressed, accidentally runs over a pedestrian after a couple of drinks at the bar. Terrified he’ll go to jail for vehicular manslaughter, Oliver learns that Roberta is not only a skilled embalmer, but also the town’s coroner and Police Chief Knickle’s (Nigel Bennett) daughter.

After staging the scene to look like the pedestrian suffered a fatal fall during one of his nightly walks, Roberta handles the autopsy, giving Oliver his first customer at the funeral home when the victim’s wealthy family comes to pay their respects. This creates a twofold problem. First, locals grow suspicious about the man’s death, meaning potential witnesses may need to be dealt with, something Roberta seemingly has no qualms about. Second, Roberta suggests sabotaging Wayne Snarr so they can get the funeral home’s books back in black once they’re the only game in town again.

The body count in Just Buried keeps climbing because Oliver and Roberta want to protect themselves, but they also realize they’ve stumbled onto a disturbingly effective business model. Dead people need funerals, funeral homes need dead people, and Roberta knows how to make people dead as if she’s been quietly planning something like this long before Oliver came into the picture. Oliver, whose nose starts bleeding whenever pressed by Chief Knickle, becomes the primary suspect in the string of deaths. Roberta, given her unique position in a small town where everybody knows everybody, remains calculating enough to stay one step ahead of the authorities.

Expert-Level Escalations

What makes Just Buried far better than its reputation suggests is how perfectly Jay Baruchel is cast as Oliver Whynacht. Everything I dislike about Baruchel’s on-screen presence in films like 2010’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice translates perfectly here. Every time Oliver gets in trouble, I expect him to start huffing and puffing before blurting out “gee whiz,” or something equally irritating. In this film, that personality trait works because he’s not reluctantly embarking on a magical adventure, but instead spiraling through a steadily escalating situation that could land him behind bars for the rest of his life.

Rose Byrne’s portrayal of Roberta Knickle is equally commendable here. At first, she comes off as an eccentric yet helpful accomplice in the incident that kicks off the gruesome chain of events in Just Buried. As Oliver spends more time with her, it becomes clear she’s a low-key psychopath whose reach and influence over the community is far wider than anybody would ever expect. The result is a morbidly hilarious mystery thriller that’s sharper and funnier than it has any right to be.

Just Buried is currently streaming on Netflix.

Entertainment

Samara Weaving Made A Subversive, Extremely R-Rated Thriller Before Her Fame

By Chris Snellgrove

| Published

Steven Yeun became a horror icon thanks to The Walking Dead, and Samara Weaving became a scream queen thanks to movies like Ready or Not and The Babysitter. In 2017, these two teamed up to create the most subversive horror movie ever made: Mayhem, which is about killing your bosses in the most brutal way and getting away with it thanks to an insane legal loophole. It’s a fast, frenetic film that turns the zombie genre on its head, and you can now stream this macabre masterpiece for free on Tubi.

The premise of Mayhem is that Steven Yeun plays a lawyer with a very specific claim to fame. He helped set the legal precedent that those infected with the Red Eye virus (which removes inhibitions and morality but otherwise leaves intelligence intact) are not liable for what they do during this altered state.

However, he loses his job on the same day that his building is flooded with the virus, resulting in every employee being quarantined until the virus runs its course. At this point, he decides to team up with a disgruntled client (Samara Weaving) to kill his bosses, knowing full well he won’t have to face any legal repercussions for any violent mayhem he causes.

A Cast That Bleeds Pure Talent

The cast of Mayhem is lean and mean, with Steven Brand (best known for Saw X) playing the amoral boss that our plucky protagonists are determined to kill. One of our heroes is played by Samara Weaving (best known for Ready or Not), whose insanely unpredictable character serves as the film’s ultimate chaos agent. Our other protagonist is played by Steven Yeun (best known for The Walking Dead), and his character has so much charisma that it’s hard not to support his goal: getting away with murder against the worst boss you could possibly imagine.

When Mayhem came out, it impressed reviewers who were hungry for more than just another horror flick. On Rotten Tomatoes, it has a rating of 84 percent, with critics praising the movie’s stylish violence and dark humor. They particularly commended the movie for tying its bonkers fictional plot to real-world economic anxieties, which serves to elevate the film without turning everything into a preachy mess.

Violence Has Never Been Sexier

I first saw Mayhem when it appeared on The Last Drive-In, the popular Shudder program hosted by horror legend Joe Bob Briggs. As Briggs described the movie, I had a bad feeling that the Red Eye virus would be nothing more than an excuse to turn characters into mindless zombies. After watching Steven Yeun’s Glenn get violently murdered on The Walking Dead (the exact point that I walked away from the show), I wasn’t really in the mood to see the actor tangle with mindless zombies yet again.

However, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that this wasn’t really a zombie movie; instead, the Red Eye virus is just a plot MacGuffin to explain why an entire building of stuffy lawyers would suddenly transform into violent killers. They aren’t mindless, either, and the fact that everyone retains their intelligence is a big part of why this movie is so scary. Instead of transforming into slow, shambling monsters, everyone in the building becomes someone with the morality and violent appetites of movie monsters like Hannibal Lecter.

I was also impressed by the bonkers premise in which our lawyer protagonist has figured out that he can attack and even kill his employers without seeing so much as a day of jail time. In this way, Mayhem channels movies like The Purge, asking viewers to consider what they would do if they had a certain amount of time (in this case, eight hours before the virus dissipates) to commit any possible crime. Anyone watching who has ever had a crazy jerk of a boss (which is basically, well, everyone watching) will also sympathize with the plight of a protagonist fighting against a broken system of capitalism in the only way he knows how.

A Freaky Film Worth Fighting For

In addition to the great premise and tight script, the movie delivers everything a horror fan could ask for: killer action, a perfect pace, and entire buckets full of blood. Steven Yeun and Samara Weaving also make the perfect onscreen team, each of them utilizing their genre experience to bring their characters to vivid, violent life. Overall, I found Mayhem to be one of the freshest horror films of the last decade, and the biggest problem with this movie is that not enough people have seen it!

You can change that by streaming this subversive horror classic for free on Tubi. Mayhem is a great movie to watch for anyone looking for a new take on an old genre or who simply wants to see two veteran performers chew the scenery in the most captivating way. Of course, it’s also the perfect movie for another group of viewers: anyone who needs a bit of catharsis after working for a terrible boss day in and day out!

Entertainment

Demi Engemann Wants Marciano Brunette’s Suit Against Her Dismissed

“Secret Lives of Mormon Wives” star Demi Engemann is firing back in court at “Vanderpump Villa” star Marciano Brunette … claiming Marciano’s lawsuit alleging defamation over her sexual misconduct allegations is a “sham” that was only filed in an attempt to get even.

In new legal docs, obtained by TMZ, Demi is asking a judge to toss Marciano’s lawsuit, which she claims was brought “solely to gain media attention” and “punish [Demi] for exercising her First Amendment right to speak out concerning [Marciano’s] misconduct.”

ICYMI … Last year, Demi called Marciano a “sexual predator” and claimed he kissed her against her will … but Marciano says the interaction was consensual, then later reframed as “sexual misconduct and then as sexual assault” to give Demi a storyline.

But the new court papers filed by Demi claim Marciano was far from a model of purity. In the docs, Demi alleges that not only did Marciano have a reputation for sexual misconduct and predatory behavior … she claims he was “proud of it.”

She says Marciano bragged about how his workplaces had to make a “special policy prohibiting him from sleeping with other employees” because she claims Marciano said he had “slept with an ‘extraordinary’ number of employees.”

Waiting for your permission to load the Instagram Media.

Notably, Marciano actually posted an Instagram reel following his lawsuit filing last year, which featured a trending sound about “getting even.”

Demi wants Marciano’s lawsuit dismissed and for him to pay her attorneys’ fees and costs as well.

Entertainment

Extreme Mystery Thriller Is A Perfect Case Of Second-Hand Revenge

By Robert Scucci

| Published

Vigilante justice is often portrayed in films through masked superheroes or hardened but well-intentioned police officers who are tired of always seeing the bad guys win. 2023’s Walden introduces its quirky brand of vigilante justice through a frustrated stenographer who has access to countless court records and starts noticing the coincidences that pile up through his millions of keystrokes. It’s the story of a man with a front row seat to some of the worst crimes that pass through the courtroom, who finally snaps after watching enough guilty people walk away without receiving the punishments they deserve.

Between the acts of brutality found in Walden is an underlying sweetness from its titular protagonist (Emile Hirsch), who simply wants to see bad people go away. The problem is that he’s such a nice guy that he doesn’t quite know how to carry himself in heightened situations, which lands him in more trouble than even the most hardened private eye could reasonably handle.

Documenting Cases Leads To Cynical Places

When we’re first introduced to Walden Dean, there’s literally nothing to dislike about him. He speaks softly, with a gentle Southern drawl, and he’s excessively polite to everyone he encounters, not because he’s trying to pull one over on anybody, but because he’s genuinely kind.

A true master of his craft, Walden is well on his way to accomplishing the unthinkable by typing 360 words per minute with startling accuracy. This particular skillset becomes the catalyst for his transformation, because those skilled hands are responsible for documenting every grisly case that passes through the courtroom under Judge Boyle (David Keith).

When a fainting spell leads to a potential terminal brain tumor diagnosis, Walden starts thinking about his purpose in life, and it doesn’t take long for him to find one. After learning that murderer Norman Bolt (Ben Bladon) walked free on a technicality after burning his own daughter to death in an oven, he springs to action, deciding he has nothing left to lose. Convinced he’s found his calling, Walden pulls out old case files with the intention of tracking down guilty parties and delivering the punishments he believes they deserve.

What Walden doesn’t anticipate, though, is a larger conspiracy that surfaces when his mentally handicapped friend George (Luke Davis) is wrongly implicated in a string of child disappearances and arrested by detectives Bill Kane (Shane West) and Sally Hunt (Tania Raymonde). As Walden’s brand of vigilante justice escalates, the stakes climb quickly. His days are numbered. His friend is in serious trouble. Authorities are catching on to his totally justified but still totally illegal slayings. And looming over everything is a much bigger case that has been brushed under the rug for years.

You Can’t Not Like This Guy

Walden works so well because Emile Hirsch dials the wholesomeness up to 11. He’s a typing nerd who suddenly finds himself way in over his head after learning he might not have much longer to live. He has seen firsthand how often people avoid justice for their horrific crimes, and he has the paper trail to prove it. He carries out acts of violence that mirror the ones committed by his targets, and he does it all with near childlike innocence and Southern charm.

Even if Walden is technically the bad guy for taking the law into his own hands, it never feels like he’s in the wrong. His intentions are pure. He still shows up week after week trying to hit that per-minute word count that would make him a legend, because at the end of the day, he takes pride in his work, and he’s simply on a side quest.

They say nice guys finish last, but in Walden, Walden Dean gets the last laugh, and it’s so satisfying to watch. If you want to type along to the subtitles while solving this murder mystery, you can stream Walden for free on Tubi as of this writing.

Entertainment

Hugh Hefner’s Widow Demands Investigation Into Playboy Founder’s Sex Diary

Hugh Hefner’s Widow

Investigate His Secret Sex Diary!!!

Published

Hugh Hefner kept a sex diary full of lurid descriptions and thousands of nude images of his conquests, at least according to his widow … and she’s fighting to keep it all under wraps.

Crystal Hefner and her attorney, Gloria Allred, announced Tuesday they believe Hef’s sex diary contains around 3,000 photos of women — some possibly underage — before, during and after sex.

Hugh is famous for his Playboy Magazine empire, but Crystal and Gloria says the scrapbooks are personal nudes and not photos that were ever shown in Playboy. They say Hef’s alleged sex diary dates back to the 1960s … with names of sexual partners matched with sex acts.

And, get this … they say Hef even tracked some of his partners’ menstrual cycles.

Crystal claims the sex diary and photos are waiting to be scanned and digitized by the Hugh M. Hefner Foundation … but she says she didn’t consent for any of her photos to end up in someone else’s hands, and she’s certain many of Hef’s sexual partners fall in the same boat. Plus, she says she’s gotten no clear answer from the foundation about where the diary is, which is also concerning.

Crystal had been the head of the foundation until Monday when, after expressing concerns over the photos and diaries, the board of the foundation removed her.

Gloria is calling on the Attorneys General of California and Illinois to investigate the alleged sex diary and keep all images and mentions private.

Crystal was married to Hef when he died in 2017.

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Tech7 days ago

Tech7 days agoSpaceX’s mighty Starship rocket enters final testing for 12th flight

-

Video1 day ago

Video1 day agoBitcoin: We’re Entering The Most Dangerous Phase

-

Tech3 days ago

Tech3 days agoLuxman Enters Its Second Century with the D-100 SACD Player and L-100 Integrated Amplifier

-

Video5 days ago

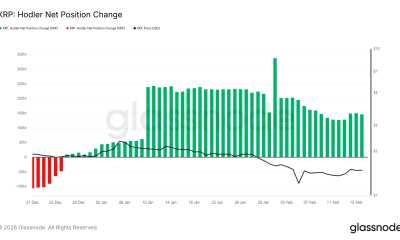

Video5 days agoThe Final Warning: XRP Is Entering The Chaos Zone

-

Tech21 hours ago

Tech21 hours agoThe Music Industry Enters Its Less-Is-More Era

-

Video16 hours ago

Video16 hours agoFinancial Statement Analysis | Complete Chapter Revision in 10 Minutes | Class 12 Board exam 2026

-

Crypto World4 days ago

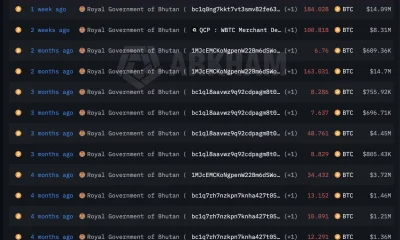

Crypto World4 days agoBhutan’s Bitcoin sales enter third straight week with $6.7M BTC offload

-

Crypto World6 days ago

Crypto World6 days agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Video6 days ago

Video6 days agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

Crypto World16 hours ago

Crypto World16 hours agoCan XRP Price Successfully Register a 33% Breakout Past $2?

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours agoGB's semi-final hopes hang by thread after loss to Switzerland

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoThe strange Cambridgeshire cemetery that forbade church rectors from entering

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBarbeques Galore Enters Voluntary Administration

-

Crypto World7 days ago

Crypto World7 days agoCrypto Speculation Era Ending As Institutions Enter Market

-

Crypto World5 days ago

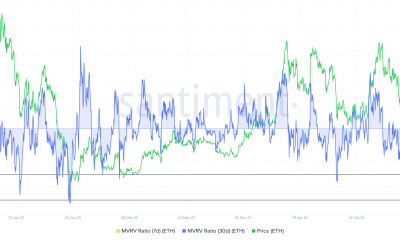

Crypto World5 days agoEthereum Price Struggles Below $2,000 Despite Entering Buy Zone

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoMan dies after entering floodwater during police pursuit

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoKalshi enters $9B sports insurance market with new brokerage deal

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoUK construction company enters administration, records show

-

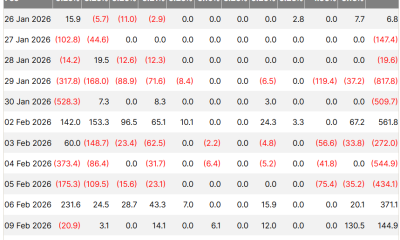

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoBlackRock Enters DeFi Via UniSwap, Bitcoin Stages Modest Recovery