Politics

Russia and Israel protected by Olympics committee

A Ukrainian athlete was disqualified from the Winter Olympics for a helmet which depicted fellow athletes whom Russia had murdered.

The BBC labelled it:

The Games’ biggest controversy so far.

The Ukrainian athlete, Vladyslav Heraskevych, was wearing a helmet that displayed images of more than 20 fellow Ukrainian athletes, all of whom Russia has murdered since the start of its invasion.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) made the decision due to Heraskevych’s:

refusal to comply with the IOC’s Guidelines on Athlete Expression. It was taken by the jury of the International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation (IBSF) because the helmet he intended to wear was not compliant with the rules.

The IOC Rule 50 states:

No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.

However, nowhere on his helmet did it mention war, Russia, or how Russia killed these people.

Astounding hypocrisy over Russia

At the very same Winter Olympics, Maxim Naumov, an American figure skater, held up a photo of his dead parents as he received his final score.

His parents were world champion figure skaters – but they competed in two Olympics for Russia.

So, athletes are allowed to celebrate dead Russians, but not dead Ukrainians?

Since then, Heraskevych has accused the IOC of fuelling Russia’s propaganda. He added:

it does not look good. I believe it’s a terrible mistake that was made by the IOC.

But the IOC’s hypocrisy doesn’t end there.

Israel is allowed to compete in the event – a literal genocidal terrorist state, with team members who served in the genocidal Israeli Defence Forces who have committed atrocities against Palestinians. Meanwhile, the IOC banned a Ukrainian athlete for wearing a helmet that might upset Putin.

One Swiss commentator called out the Israeli team during a bobsled race. As the Canary previously reported:

Stefan Renna, who works for Swiss Radio and Television (RTS), pointed out that bobsled racer Adam Edelman calls himself “Zionist to the core“. Edelman has also made numerous social media posts supporting Israel’s Gaza genocide. Renna even used the g-word – genocide – that terrifies UK corporate ‘journalists’, referring to the findings of the UN International Commission of Inquiry.

The IOC has maintained that both Israel and Palestine should have equal opportunity to compete at the Games. However, Israel has a team at the Winter Olympics, whilst Palestine does not.

Whilst Palestine has never entered the Winter Olympics, only the summer games, we can put that down to the lack of infrastructure and the continued system of apartheid, which means the country lacks the funding to support its athletes’ development to an elite level. Perhaps Palestine could put a Winter Olympics team together if Israel stopped razing them to the ground every few years.

Israel has murdered over 800 athletes and sporting officials since October 2023. That figure includes more than 100 child athletes. The terrorist state has also destroyed 273 sports facilities – meaning Palestinian athletes who survived have nowhere to train.

Make your mind up

The IOC has banned both Russian and Belarusian athletes from competing under their own flags. Meanwhile, there has, of course, been no equivalent ban for Israeli athletes.

However, in September, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) lifted its ban on athletes from both countries competing at the games, which doesn’t make sense when Russia’s attacks on Ukraine are still ongoing.

The IOC needs to make up its mind.

Either athletes cannot remember and dedicate their victories or performances to the dead, or they can. And the answer to that should not depend on where they come from.

Similarly, can murderous regimes compete under their state’s flag, or not? Of course, they unequivocally should not. But the IOC cannot have one rule for one and one rule for another.

Obviously, we know why this is. Israel is funding politicians left, right and centre who can put pressure on sporting bodies to have countries banned as and when they see fit, as Lisa Nandy did only this week.

Moreover, the West, the mainstream media, the majority of our politicians, and apparently the IOC, seem to care more about dead white people than they do about dead brown people. The hypocrisy stinks – and Israel should not be allowed to compete whilst simultaneously murdering Palestinians. The double standards are strewn everywhere.

Featured image via ABC News (Australia) & Euro Media News / YouTube

Politics

Palestine Action defendants charges dropped

Eighteen defendants from Palestine Action have now been acquitted of aggravated burglary. Earlier this month, a jury cleared six of the Filton24 of aggravated burglary, while leaving the charges of criminal damage and violent disorder undecided. These charges are in relation to direct-action taken targeting Israeli arms company, Elbit Systems in Bristol.

Middle East Eye reported that:

Following the decision to drop the charges, five of the defendants – William Plastow, Ian Sanders, Madeline Norman, Julia Brigadirova and Aleksandra Herbich – were granted conditional bail.

Plastow, Sanders and Norman have been held on remand for the longest period of the 18- spending 18 months in prison. Birgadirova and Herbich has been imprisoned since November 2024.

Bail applications for another eight defendants will be held on Friday.

Palestine Action targeting

Today’s announcement comes as the prosecution have “reconsidered the sufficiency of the evidence”. This move appears to suggest it would be unlikely to achieve the guilty verdicts it is clearly aiming for. However, at this late a stage in a criminal case, the prosecution could not just drop the aggravated burglary charge against the remaining defendants. This left it no option but to concede defeat on that charge if it wished to change course.

Consequently, concerns have resurfaced that the prosecution and government could reconsider their strategy and pursue different charges with a stronger likelihood of conviction.

All of the Filton24 were acquitted of aggravated burglary. SAY IT. https://t.co/ohMIDuUYVb

— Huda Ammori (@HudaAmmori) February 18, 2026

Victory: for now

The Palestine Action defendants have received popular support amongst pro-Palestinian activists and groups. In fact, many pensioners across the country have been seen risking arrest for daring to show public support for then proscribed Palestine Action (PA). The direct-action group has protested against Israel’s settler colonialism for many years, and its members have long sought to call attention to those arming the Zionist entity. The case against them refers to a break-in near Bristol of an Elbit Systems site known to be providing arms and supplies to Israel.

Citizens across the UK have taken to protests in every city since October 7th, 2023, making it clear that the majority of British people do not support the ongoing genocide in Gaza. Moreover, leading Holocaust scholars across the globe and the International Court of Justice in The Hague have identified this as a genocide, while the International Criminal Court has moved forward with arrest warrants at the direction of Prosecutor Karim Khan.

We wrote a few days ago on the court ruling that the proscription of Palestine Action, brought because of their acts of protest, was deemed disproportionate. Yet little has really changed, as Skwawkbox wrote:

The decision was made by a panel of judges who all have strong links to Israel, underscoring just how far the Starmer regime overstepped human rights legislation. It is almost certain to try to appeal, despite the exposed web of lies it created to try to justify the ban.

Nevertheless, people are rightfully celebrating this reprieve across social media:

Victory after victory … what an incredible start to Ramadan, the month of victory https://t.co/zrI9NkAiNi

— Fahad Ansari 🇵🇸 (Stop the Gaza genocide) (@fahadansari) February 18, 2026

Another victory for Palestine Action, defeat for the UK government’s support of genocide. https://t.co/Lw8wj3dV0l

— Syksy Räsänen (@SyksyRasanen) February 18, 2026

Great news BELOW!

There is a CHASM between what the politico-media “elites” think about the GENOCIDE in Gaza and what the general public think

The general public is decent & humane

The “elites” are immoral & cruel https://t.co/Hrw6j3dBgt

— Tom London (@TomLondon6) February 18, 2026

Returning home to their loved ones

Some defendants have since been granted bail following being declared ‘not guilty’ of the original charge of aggravated burglary. This represents a huge relief for the defendants given they will now be able to return home to their loved ones. Nevertheless, some still remain on remand awaiting trial, signaling that not much has changed regarding our government’s intentions.

As Investigative journalist Asa Winstanley reported on X:

BREAKING: Aleksandra Herbich and Yulia Brigadirova both also granted bail in Filton 24 hearing. Both have been on remand for 15 months.

In total, five Palestine Action activists have been granted bail today. Four are expected to be released today.

Brigadirova has a second case… pic.twitter.com/YO6Hkq9WHC

— Asa Winstanley (@AsaWinstanley) February 18, 2026

Although we at the Canary recognise this as a significant victory, it should not be mistaken for a safeguard against future action by the UK government or the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

It is clear that accepting defeat on this charge will leave a bitter taste for the Starmer government. Their premiership is already facing serious scrutiny over its significant levels of funding from the Israel lobby. This announcement today raises legitimate concerns that the prosecution may return with renewed determination, pursuing alternative charges it believes are more likely to secure convictions.

The broader fear we must acknowledge is that this effort is not merely about this case, but about setting a precedent – using the Filton 24 as a warning to deter dissent and protest in support of Palestinians.

As Richard Sanders pointed out on X, the British Government have no love lost for these defendants. Something they made clear recently during the defendants’ principled hunger strikes:

A reminder that the government was prepared to let 4 of these people die on hunger strike. https://t.co/9zHFayUSP9

— Richard Sanders (@PulaRJS) February 18, 2026

We must stay vigil

We reported on Palestine Action co-founder Huda Ammori’s comments on the CPS’ case against the six acquitted by jury. Skwawkbox wrote:

This case from the start has been heavily politicised.

The CPS are now publicly declaring, before the court hearing, that they’ll seek a retrial, despite the defendants having already spent 18months in prison without a single conviction.

This is political theatre.

Sadly, we believe today’s victory may prove similarly short-lived. The actors are currently off-stage changing their outfits and rehearsing their lines. But we must not forget, political theatre is still heavily permeating through this oppressive criminal case against the Palestine Action defendants.

We must stay vigilant and ready for whatever may follow this temporary reprieve.

Featured image via the Canary

Politics

25,000 back calls for NatureScot to end controversial guga hunt

More than 25,000 people have now signed a petition calling on NatureScot to stop licensing the controversial guga hunt. And pressure continues to mount on Scotland’s nature agency.

The guga hunt – killing young gannets

Each autumn, a group of men from the Isle of Lewis travel to the remote uninhabited island of Sula Sgeir to capture and kill flightless gannet chicks (“guga”) for food. The hunters use poles to dislodge the young birds from the cliffs and then batter them to death.

The activity is part of a historical tradition and takes place under authorisation from public body NatureScot. The agency decides whether to grant a licence each year there’s an application, subject to conservation tests.

Protect the Wild created the petition. It argues that NatureScot is failing to meet evidential thresholds when issuing these licences and should not continue authorising the guga hunt.

Mounting public pressure recently prompted NatureScot to issue a public statement. It acknowledged the “strong feelings” about the guga hunt and confirmed that its board is considering people’s concerns.

In its statement, NatureScot said:

We understand there are strong feelings about the guga hunt, and that some people will disagree with it taking place. The hunt is recognised in law under the Wildlife and Countryside Act…Our role is to make licensing decisions based on the most recent scientific evidence.

NatureScot confirmed that in 2025 it reduced the permitted take from 2,000 birds to 500 following survey data collected after avian flu outbreaks. And it said that it granted a licence on the condition that the hunters killed the birds “humanely”.

Insufficient monitoring

But Protect the Wild says the Sula Sgeir gannet colony remains in decline and that allowing even a reduced guga hunt risks further damage. It also questions how NatureScot can guarantee the killing is humane when it does not directly monitor the process.

Devon Docherty, Scottish Campaigns Manager at Protect the Wild said:

Sula Sgeir is now the only Special Protection Area for gannets in Scotland that has fallen below its official citation level.

NatureScot continues to grant licences knowing the gannet colony is vulnerable, the hunt harms other breeding seabirds, and that they cannot verify whether the chicks are killed humanely – they simply take the hunters’ word for it.

With tens of thousands of people now calling for it to stop, the continued licensing of the guga hunt is becoming increasingly difficult for NatureScot to justify.

NatureScot has stated that if a new licence application is received for 2026, it will be brought before its Board for decision.

Protect the Wild says it will continue urging NatureScot to reject future licence applications. And it’s calling on the Scottish government to remove the legal exemption that allows the guga hunt to take place.

Featured image via John Ranson / the Canary

Politics

fasting among tents and rubble

Two years after a war that left widespread destruction across the Gaza Strip, Ramadan returns amid an extremely complex humanitarian crisis. Feelings of joy at the arrival of the holy month are mixed with grief, displacement and the collapse of basic services.

The population welcomes Ramadan burdened by loss. Longstanding traditions have been replaced by tents and queues for aid.

Ramadan in Gaza — a pressing humanitarian situation

More than two million Palestinians are living in severe hardship. There are acute shortages of food and drinking water, and purchasing power has fallen to unprecedented levels amid widespread unemployment. A large segment of the population now relies on soup kitchens and relief aid to meet daily needs. Even then, supplies cover only a fraction of demand.

The health sector faces serious challenges. There are ongoing shortages of medicines, medical supplies and laboratory materials. These gaps threaten to increase health risks during the holy month, particularly for chronically ill patients, children and the elderly.

Medical authorities warn of the consequences of continued restrictions on humanitarian supplies. Ramadan is traditionally a season of solidarity and support, yet conditions remain dire.

Modest meals and absent rituals

Each evening, families gather for modest iftar meals. These are often limited to bread, vegetables and whatever relief supplies are available. Before the war, the holy month was marked by large family feasts. Extended families rarely gather now. Many have been scattered by displacement and the loss of their homes.

Street decorations and festive lanterns have largely disappeared. Children no longer roam markets buying Ramadan lights. Instead, small temporary lamps replace traditional decorations.

Some families craft handmade ornaments inside their tents. It is a small attempt to preserve the spirit of the month despite harsh conditions.

Mosques between destruction and temporary alternatives

Many mosques were damaged during the war. Some remain completely out of service, depriving residents of a central part of Ramadan.

In response, residents have set up temporary prayer spaces inside tents or damaged schools. Prayers are performed with whatever resources are available. Despite ongoing security concerns and tensions, many remain determined to perform Taraweeh prayers. For some, these rituals provide rare moments of peace amid instability.

Childhood in Gaza looks different this year. Children who have lost homes or family members play between rows of tents. They carry simple lanterns made from available materials.

They try to recreate the joy they associate with Ramadan, even while surrounded by rubble.

Parents strive to create moments of warmth within the family. They prepare simple meals together or organise small group prayers to maintain social bonds.

Between the ‘yellow line’ and the expanding buffer zone

Ramadan’s arrival coincides with ongoing changes on the ground. These shifts have altered Gaza’s demographic map.

A 9 February report by the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Observatory described what it called a “silent and slow genocide.” It said this goes beyond bombardment to include structural changes. According to the report, the buffer zone is expanding along the so-called “yellow line,” dividing the Strip into two areas. Israel controls land to the east, which the report says represents more than half of Gaza’s territory.

The line, previously expected to remain fixed, has reportedly advanced around 1.5 kilometres into residential areas. Additional neighbourhoods have been annexed, forcing more families to flee.

Ramadan in Gaza, between loss and resilience

Ramadan in Gaza this year is not only a month of worship. It is also a test of resilience.

Homes have been destroyed, families dispersed and daily life remains under pressure. The holy month feels very different from before the war. Yet residents continue to observe Ramadan as best they can. They stress that its spirit lies in patience and solidarity rather than outward celebration.

Between forced hunger and religious fasting, Gazans are redefining Ramadan. Even amid devastation, many see it as a space for hope and quiet endurance.

Featured image via Aljazeera

Politics

The House Opinion Article | Whitehall’s Whispers: Inside The Antonia Romeo Row

7 min read

As the Prime Minister prepares to appoint Antonia Romeo as Cabinet Secretary, Ben Gartside looks at the fierce battles to block her appointment

In Downing Street, a coronation as new Cabinet Secretary is anticipated for Antonia Romeo. So impressed is the Prime Minister that an expedited process is being sought so the Home Office permanent secretary can be appointed at speed.

Romeo would become the first ever woman to hold the position of Cabinet Secretary, though a whisper campaign against her has already formed.

Last week, Lord McDonald launched an unprecedented attack via Channel 4, inviting Downing Street to go looking for bodies in Romeo’s resume.

In his televised interview, the former Head of Diplomatic Service said: “Due diligence is vitally important, the Prime Minister has recent bitter experience of doing the due diligence too late. It would be an unnecessary tragedy to repeat that mistake… if [Romeo] is the one, in my view, the due diligence has some way still to go.”

That intervention meant that previous allegations of bullying and questions about her use of expenses in 2017 resurfaced – despite the fact they were investigated at the time and Romeo cleared.

The interview also brought into the light an animus that has been an open secret in Whitehall for years. It began, it seems, around the time McDonald was appointed Permanent Under Secretary of the Foreign Office in 2015. In his memoir, Leadership, McDonald describes a “senior colleague” as “stylish, energetic, warm, a bit iconoclastic and a bit marmite”, though he adds “preternaturally sensitive to” feedback.

The ”senior colleague” is widely assumed to be Romeo, who was special envoy to US tech firms at the time and was the subject of an investigation into bullying and expenses during his time at the helm.

While he managed the investigation, the ultimate arbiter was Jeremy Heywood. In his memoir, McDonald described his conclusions as “comprehensive and damning” and said her impending promotion to permanent secretary should have been paused or cancelled altogether. However, Heywood intervened to protect his mentee, Romeo, and the promotion still went ahead.

In another section, McDonald recounted blocking the “senior colleague” from what appears to be the US ambassador’s job in 2019.

“The senior ranks of the civil service are chock-a-block with people who didn’t do anything for very long – they agitate to move on and up quickly. Apparent success must be banked professionally before its shortcomings come to light.”

McDonald was on scathing form, describing how Romeo had cashed in on her success managing reforms around probation, before the changes were revealed to be an unmitigated disaster.

He said: “The most senior civil servants had moved on, promoted on the back of a single ‘success’… none of whom has ever suffered professionally for the flawed advice on which the Lord Chancellor based his decisions… The self-promoters not only relentlessly push their own claim, but they deter others from having a go.”

Friends of Romeo label much of the chatter around her sexist – no other senior civil servant has faced as much judgement outside the realms of performance and delivery, or as much focus on their character.

One top civil servant, an ally of Romeo, described McDonald’s behaviour as outrageous.

“At all levels of the civil service, there is a feeling of sheer outrage that a retired civil servant could launch an attack on an existing one, knowing she can’t defend herself against it. It is a drive-by on her, and deeply damaging to the institution.”

She confounds the old nostrums of the civil service

Dave Penman, general secretary of the FDA union, tells The House: “She’s an ambitious woman who doesn’t mind a bit of publicity. A lot of underlying rumours around her are an example of sexist, misogynistic culture. Lord McDonald’s talk around vetting is nonsense. She’s been vetted within an inch of her life already; she can see documents that cabinet ministers don’t have access to.

“She’s quite a dynamic, people-focused leader. I was quite impressed with that, and I’m of the view that senior leadership in the civil service should have more of a profile. She’s much more in the leadership role than the courtier role, and that’s what the civil service needs right now.”

That being said, concerns around bullying behaviour still require probing. One civil servant who worked under Romeo says she responded poorly to bullying allegations levelled at former cabinet minister Dominic Raab, and had ignored a slew of staff leaving his private office.

Penman disagrees: he sees Romeo as the only permanent secretary to have been shown by the investigation to have confronted Raab on his behaviour.

Others are more robust – albeit from behind the cloak of anonymity. A minister was quoted in The Sun as saying McDonald was part of a “posse of old baldies throwing dirt on a brilliant woman for having a bit of chutzpah”.

Sir Matthew Rycroft, a former colleague, and Rupert McNeil, the former head of government HR, are among those who have defended Romeo on the record.

Allies bill Romeo as a reformer, eager to enact change within Whitehall at the best of the government. In her office, a poster reading “Keep Calm and Carry On Transforming” sat above her desk, unwilling to accept stasis within the government.

Through this reputation, Romeo has built an unlikely list of allies: She was Liz Truss’ first choice for permanent secretary of the Treasury, before ultimately renegeging and preferring a Treasury insider. Now, numerous Labour advisors are admirers, with Shabana Mahmood’s success at the Home Office being ably supported by Romeo.

Robert Buckland, who worked with her during her time at the Department for Justice, offers a glowing endorsement.

“I think she is an extremely impressive person. She’s not a conventional backroom figure; she’s not scared of publicly projecting herself, but that shouldn’t be a block on her becoming first female cabinet secretary.

“She confounds some of the old nostrums of the civil service. Seen not heard, be aware of the hierarchy. As a politician, I didn’t have time for that. Running a department during Covid, I needed flat structures and quick decisions.

“She doesn’t play the old civil service game, hiding behind hierarchies and using delay as a tactic.”

Alex Chalk, a former justice minister, describes Romeo in similarly favourable terms to The House magazine: “She is whip-smart, highly intelligent and knows Whitehall inside out. She also has good judgement, meaning she gives candid and practical advice about how best to deliver on ministerial priorities. Crucially, her instinct is to develop solutions, not simply point to problems. She is the reboot the civil service urgently needs.”

Former secretary of state Brandon Lewis echoes this, crediting Romeo for bringing an end to the bar strike and relieving pressure on prison spaces. “[Romeo] is focused, engaging and always has a smile to share, great to work with and a real leader of her team,” he says.

However, one policy wonk points back to her time in probation at justice as an example of the double-edged sword of being popular with officials.

“In 2014, the probation reforms were rushed on the behest of Chris Grayling, as he wanted to be appointed home secretary after the election. The data wasn’t ready, contractors were excluded from bidding in order to meet political goals. If Romeo hadn’t been so popular with politicians, perhaps the reforms would have been more successful.”

A Cabinet Office spokesperson said: “Antonia Romeo is an outstanding leader with 25 years of public service. She has been appointed to three different Permanent Secretary roles and has led hundreds of thousands of public servants to deliver for governments of all stripes.

“As we have repeatedly said, one formal complaint was raised 9 years ago, which was thoroughly investigated. The allegations were dismissed on the basis that there was no case to answer.

“It is entirely inappropriate to resurface dismissed HR proceedings almost a decade later.”

Lord McDonald declined to comment on the book excerpts.

Politics

UK leaders warned over war crimes scrutiny

Serious UK prime ministers should be afraid to discipline special forces troops over war crimes because they are so popular with the public. That’s according to Dr. Simon Anglim, who wrote a lengthy essay on the UK’s new ranger and special operations units.

The essay makes a range of (in fairness, very interesting) points about shadowy deployments overseas — including to Ukraine. But the King’s College War Studies lecturer — yes, it’s the KCL War Studies people again — also warned that the current Haddon-Cave inquiry into war crimes in Afghanistan could have serious implications for the use of UK Special Forces (UKSF).

UKSF is distinct from the ranger units and remains heavily protected from even basic democratic scrutiny. The government refuses to comment on what they do — even in parliament.

It’s a distinctly British practice. None of our major allies refuse point blank to comment on their special forces operations. Yet we do. As the now-defunct Remote Control project pointed out in a 2016 report:

this blanket opacity policy is not standard practice, and the UK is lagging behind its allies on transparency over its use of Special Operations Forces (SOF). The US, Australia, and Canada are all more transparent about their deployment of SOF than the UK.

The practice is also deeply undemocratic:

This leaves the British public, and the parliament that represents them, among the least-informed of their foreign allies about the government’s current military activities in places like Syria and Libya stymying informed debate about the UK’s role in some of the most important conflicts of our age.

So what’s happening then?

Special Forces afraid of the light

Anglim said the threat of accountability over the Afghan allegations was “a shadow hanging over UKSF”:

The ongoing Inquiry, presided over by Lord Justice Haddon-Cave, investigating allegations that UKSF members committed unlawful killings in Afghanistan in 2010.

Ireland legacy allegations were also an issue. The SAS investigation:

runs concurrently with the Northern Ireland Coroner’s ruling that soldiers of 22 SAS were ‘not justified’ in killing three members of the Irish Republican Army in an ambush at Clonoe in Northern Ireland in 1992, and the stream of further allegations of unlawful conduct it has set off.

As Anglim pointed out, the cases are sub judice — ongoing — currently. But he expressed a concern they:

could strengthen demands for UKSF to face greater Parliamentary scrutiny, possibly via a Select Committee similar to the one overseeing Intelligence.

Clearly, public scrutiny is a terrifying prospect.

Scrutiny and pressure

This, Anglim said, could result in political pressures which might limit the use of SF:

Given the potential for security breaches and increased hostile scrutiny, this may have a freezing effect on future UKSF deployments and could alter the relationship between the Directorate and its political masters.

Presumably by ‘hostile scrutiny’ he means from the press and public. Anglim suggested he might write about it more once the cases are resolved:

but it is worth noting that, given their high status with the British public, no serious Prime Minister would want to impose collective punishment on Britain’s Special Forces and besides, they are too valuable as national assets to do this too severely if at all.

Anglim makes some very good points in his essay. He is also the definition of an establishment academic. He has worked with the US Department of Defence (currently ridiculously rebranded as the Department of War), the Sultanate of Oman, various establishment think-tanks and has given evidence on readiness to the defence committee.

Here he is talking about how Covid and Brexit affected the military:

But his warnings that some sort of basic accountability could reduce Britain’s ability to conduct secret military operations are telling. As with all things the British establishment says you must turn them upside down to understand them.

Public and journalistic scrutiny are good, actually, because they are a threat to the British ruling class’s hunger for war, war-profits — and for staying close to US imperial foreign policy whatever the cost and whoever is president. The more scrutiny, then, the better. And if ‘serious’ prime ministers would be afraid of the light of said scrutiny, let’s hope for an ‘unserious’ one.

Featured image via the Canary

Politics

Restore Britain gains nine defected Reform councillors

Seven Kent County councillors and two North Northamptonshire County Councillors have joined Restore Britain. Reform UK previously expelled six of them.

Most of these were thrown out of Reform UK when @LeaderofKCC had her meltdown in the ‘suck it up’ cabinet meeting and the video was leaked. https://t.co/w5NmJN5AH8

— Reform Party UK Exposed 🇬🇧 (@reformexposed) February 17, 2026

How do you even get expelled from Reform? Not taking bribes from Russia?

According to the Independent:

The new Restore Britain group members are Paul Thomas, Oliver Bradshaw and Brian Black, who have been sitting as the Independent Group; Robert Ford and Isabella Kemp from the current Independent Reformers Group, and independent-sitting councillors Maxine Fothergill and Dean Burns.

Nigel Farage hoped that Kent County Council would be his flagship Reform council. Look how that one turned out.

Reform won control of Kent County Council in May last year, securing 57 of 81 seats. However, only 48 councillors remain. Nine were removed after they leaked a video showing council leader Ms Kemkaran shouting and swearing at her members.

The Canary’s Joe Glenton described the video as:

a group of dysregulated middle-aged toddlers having an incredibly puerile row

Is it a picture of what’s to come with Restore?

Kent Council was described as being “a window to what a Reform UK government would be like”….

It’s been chaos, full of lies and a wannabe dictator leading it…..so they weren’t wrong!

— AxoAndy (@AxoAndy) February 17, 2026

After all, it’s the same faces, just with a few different letters.

In North Northamptonshire, Jack Goncalvez and Darren Rance have both also defected to Restore.

But Restore Britain has not even registered with the Electoral Commission yet.

Rupert – can you point me towards your Registration Details on the Electoral Commission website… pic.twitter.com/hJEnjmm3cW

— 🦋 𝗚𝗿𝗮𝗲𝗺𝗲 𝗙𝗿𝗼𝗺 𝗜𝗧 🧵 🌹 (@graeme_from_IT) February 17, 2026

Restore Britain even more racist than Reform

I can’t believe I’m saying this (except I really can), but this clown show is competing for a number one spot in the ‘more racist than Reform’ show.

BREAKING 🚨🚨🚨

Restore Britain Party members forced to elect Rupert Lowe as leader after their original 1st choice candidate shot himself in a bunker in 1945. pic.twitter.com/2L0P6cFA2X

— Politics For You (@PoliticoForYou) February 16, 2026

Rupert Lowe’s Restore Britain party is promising to sweep ‘Anti-British”, “anti-white” elements out of our universities and schools. Doing so, he is copying the Nazi playbook of 1933. If you’re not worried now, you should be. https://t.co/cLV2qCDF36

— Richard Murphy (@RichardJMurphy) February 18, 2026

But hey, what’s one more shade of blue? They’re all the same racist, ‘we hate every other country’ but Israel-loving muppets. I wonder if there’s some sort of blue attire-for-hire company setting up in Westminster.

If not, I want a commission when it goes live.

Rupert Lowe is welcoming these vile, racist muppets that are too embarrassing even for Nigel Farage and Reform with open arms.

He’s not even scraping the bottom of the barrel. He’s scraping the dregs up off the floor that no doubt have the remnants of rat shit in them.

Feature image via HG

Politics

So THAT’s How Often You Should Clean Bird Feeders

We all want to help out our feathered friends – especially in these biting winter months when their food is more scarce than usual.

But there’s one garden mistake many of us might be making that could unintentionally cause harm to the British bird population.

According to wildlife expert Kate Macrae, known to millions as Wildlife Kate, we mustn’t forget about bird feeder hygiene.

“There are many diseases that can be passed around dirty feeders, causing death to species that we actually wanted to help,” she says.

The RSPB notes that diseases such as Trichomonsis – which has been a major factor in the decline of Britain’s greenfinch population – can be spread by contaminated food and drinking water.

So, how often should be cleaning bird feeders?

Macrae recommends having a couple of high-quality bird feeders that come apart completely for cleaning. You can clean them with warm soapy water and an animal-safe disinfectant spray.

The RSPB notes feeders and baths should be cleaned once a week – Macrae agrees, and she’ll typically wipe down all ports and perches every day.

For those intent on keeping feeders filled right to the top with food, the wildlife expert, who has partnered with UK woodcare brand Protek, says high-quality food matters more than quality.

Sunflower hearts, sunflower seeds, suet pellets and balls are her top picks. She notes peanuts should be dispensed in a suitable feeder where they cannot be removed whole.

The RSPB also encourages people to not overfill their bird feeders (again, for cleanliness reasons). “Try and make sure they are being emptied every 1-2 days”, it suggested, and if you do need to refill them, make sure old food is emptied out first.

The wildlife charity recommends moving feeders regularly “to prevent the build up of bird food and droppings potentially contaminating the ground below”.

And don’t forget your bird baths and water dishes need a good clean, too.

“Again, remember that hygiene is paramount and clean the dish and put fresh water out daily,” Macrae adds.

Politics

Why You Can’t Get Over Your Toxic Ex (And What To Do About It)

We all know that Wuthering Heights is not about a love that we should aspire to, right? We know that their bond was eventually very toxic, that they mistreated each other and everybody around them, and it ended anything but happily ever after.

All of that being said, watching Emerald Fennell’s take on the novel can definitely remind you of a certain ex. Not the one you had an amicable split with, not the ‘fun summer fling’. No. This ex is the one that you had the senselessly passionate relationship with. Everything was aflame and when it ended, you went no-contact. Probably because your friends begged you to.

It’s not romantic but it’s definitely alluring: the thrill of the chase, the passion between you, the way they took up residence in your head and squeezed into every thought… they’re pretty unforgettable, probably quite toxic, and seeing a highly stylised version on-screen with this blockbuster can easily reignite certain memories.

Why you can’t get over your toxic ex

On paper it should be easy, but getting over this kind of ex is not simple, much like the bond itself – as divorce coach Carol Madden notes on Medium: toxic relationships take longer to heal from than healthier ones.

Speaking to Business Insider, relationship expert Jessica Alderson explained that these kind of relationships are a bit like an addiction, saying: “They are often characterised by extreme highs, during which relationships seem perfect and magical, followed by crashing lows, which are usually caused by a partner pulling away or acting out – this can make people feel alive.”

Once the relationship finally ends, your body can still crave this unpredictability. She added: “The emotional rollercoaster can make it harder to move on and accept that the relationship wasn’t meant to be.”

How to get over an ex

Clinical psychologist Dr Ruth Ann Harpur suggested that after a relationship breaks down, people will naturally try to seek answers about where it all went wrong – and while it’s a “crucial step” in the early moments of the breakup, it’s important not to keep going over every detail of the relationship and your ex’s behaviour.

If you get stuck ruminating, you become “tied to the past” and end up reliving the pain, she suggested. So, her advice is to: “Understand that ruminating on past abuses may feel safe but it keeps you from living fully in the present and building healthier relationships.”

She also urges people to focus on activities they really enjoy to keep busy and connect with themselves again, and to open themselves to new friendships and relationships.

Experts at Calm have a guide to getting over a relationship with advice that includes:

- Clearing out physical reminders of them.

- Allowing yourself to feel your feelings.

- Limiting or cutting contact with them, including on social media.

- Setting new goals.

- And seeking therapy.

It isn’t easy, but you can move on.

Politics

Politics Home | Thousands call on the government to stand by its promises to ban trail hunting

Fake foxes covered in blood with League ‘hunter’ on the streets of London outside the National Gallery.

Open letter handed to Number 10 as hundreds of bloody foxes appear in central London

A huge pile of bloody foxes appeared in central London yesterday [Tuesday] to highlight the scale of illegal hunting in England and Wales that has continued since the government took power.

National animal welfare charity the League Against Cruel Sports was behind the stunt, which saw a “hunter” dump 648 foxes in Trafalgar Square – one for each report the charity has received of a fox being chased by hunts since the summer of 2024.

Meanwhile, animal welfare campaigners from the League-led Time for Change Coalition Against Hunting handed in an open letter signed by more than 36,000 people in just one month to Sir Keir Starmer at 10 Downing Street.

The letter, which calls on his government to keep its promise to properly ban hunting wild animals with dogs, comes a year after a 104,000-signature petition calling for stronger hunting laws was handed in to Number 10 on the twentieth anniversary of the Hunting Act coming into force.

Emma Slawinski, League Against Cruel Sports chief executive, said: “The government isn’t keeping its promises, and the dumped bloodied foxes are there to show the scale of illegality that the government is failing to get to grips with.

“The public is repulsed by trail hunting, which is just a smokescreen for foxes and other wild animals still being chased and torn apart by hunt hounds, so we are urging the government to act immediately to end this savage blood sport once and for all.”

The government pledged to ban so-called trail hunting in its manifesto, and further promised to launch a public consultation “in the new year” when it launched its animal welfare strategy before Christmas.

This has not happened.

Emma said: “The time for change is now and the government must urgently launch its consultation, which should also include the removal of the exemptions in the Hunting Act that hunts exploit to get around the current weak law, the introduction of custodial sentences, and the outlawing of reckless, or ‘accidental’ hunting.”

Polling commissioned by the League Against Cruel Sports and carried out independently by FindOutNow with further analysis by Electoral Calculus in March/April 2024 found that 76 per cent of the public supported stronger fox hunting laws, with only seven per cent disagreeing.

A clear majority of voters in rural as well as urban areas backed new laws to stop foxes being chased by hounds and killed, with 70 per cent of people in the countryside supporting the proposal.

More about how to take part in the consultation, and how people can make their voice heard, is available here: https://www.league.org.uk/hunting_consultation

Politics

‘No taxation without representation’ must be non-negotiable

Around this time last week, I was standing in the pouring rain in West Sussex, handing out leaflets to defend something that should never have needed defending: the right of local residents to vote. The TaxPayers’ Alliance had been out across the county campaigning against the Labour government’s plan to cancel elections in 30 local authorities across England. Leading the charge were the Telegraph, which launched its Campaign for Democracy last month, and Reform UK, which had brought a legal challenge that was due to be heard in court on Thursday – and which the government was expected to lose.

But taxpayers should never have had to rely on opposition parties, newspapers and campaign groups to defend the most basic principles of democracy. Holding regular elections should be the bare minimum we expect of the people in charge.

Now, Keir Starmer has performed his latest u-turn and those local elections are back on. But let’s not dress this up as a government listening to the people. The government tried to trample over local democracy, faced the wrath of the British people and backed down.

The official justification for the cancelled elections was always nonsense. Labour’s upcoming local-government reorganisation apparently made elections too expensive, complicated and, in the words of communities secretary Steve Reed, ‘pointless’. But functioning democracies don’t suspend elections because they are inconvenient or expensive. By that logic, any government could put off elections indefinitely.

The more plausible explanation is that Labour looked at the polls, saw the wipeout coming on 7 May and decided that stripping 4.5million people of their vote was preferable to facing the consequences of their own failures.

What made it worse was what these councils were planning to do had the elections not gone ahead. Spared the inconvenience of facing voters, they weren’t even willing to show a modicum of humility or contrition by freezing council tax. Indeed, the councils that planned to delay their elections are expected to add £121million more in council tax compared with the previous year. Some of them would have been postponing elections for the second year in a row and yet they were still planning to hike bills.

The average band-D household in England is paying 16 per cent more in council tax than in 2022-23. Councillors would have been adding even more to that burden without any democratic mandate to do so. The principle of ‘no taxation without representation’ is centuries old, dating back well beyond the American Revolution. Sadly, this age-old tenet is incomprehensible to the posse of petty authoritarians we call our elected politicians.

Depending on how generously you’re counting, this is somewhere around Labour’s 14th u-turn in government. At this point, the u-turn is Keir Starmer’s only consistent governing philosophy. Announce something outrageous. Face pushback. Retreat. Repeat. Future historians trying to summarise the Starmer years will struggle to find a defining achievement, but they won’t struggle to find a defining pattern.

Now, thanks to the legal incompetence of our former prosecutor turned prime minister, councils face a scramble to organise elections they had written off. Reversing the bad decision won’t reverse the damage it caused. Taxpayers will be forced to foot the £63million bill that central government has put aside to help councils deal with the fallout from this u-turn and the chaotic reorganisation of town halls.

If Keir Starmer wants to pretend that he even has a shred of respect for the local democracy and the hard-working taxpayers that he has spent months trying to crush, there is only one thing he should be doing: bringing in an iron clad law to prevent this from ever happening again. If in future there is ever another attempt to trample on local democracy, councils should be forced to freeze council tax and all other charges. The principle is simple: no vote, no tax rise. It’s the least councils could do.

While some may take the local-elections u-turn and claim it as a win, what we won’t do is pretend it represents anything other than a government that tried to strip millions of people of their vote, failed, and is now hoping we’ll forget about it and move on. This is a stain that will indelibly mark this government for as long as the British electorate is condemned to suffer under its rule.

Anne Strickland is a researcher at the TaxPayers’ Alliance

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Video2 days ago

Video2 days agoBitcoin: We’re Entering The Most Dangerous Phase

-

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoLuxman Enters Its Second Century with the D-100 SACD Player and L-100 Integrated Amplifier

-

Video5 days ago

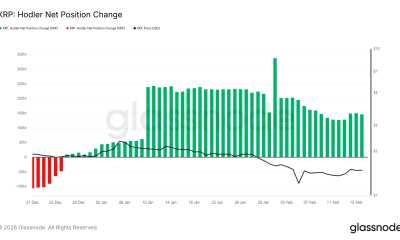

Video5 days agoThe Final Warning: XRP Is Entering The Chaos Zone

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoGB's semi-final hopes hang by thread after loss to Switzerland

-

Tech2 days ago

Tech2 days agoThe Music Industry Enters Its Less-Is-More Era

-

Crypto World1 day ago

Crypto World1 day agoCan XRP Price Successfully Register a 33% Breakout Past $2?

-

Business19 hours ago

Business19 hours agoInfosys Limited (INFY) Discusses Tech Transitions and the Unique Aspects of the AI Era Transcript

-

Entertainment5 hours ago

Entertainment5 hours agoKunal Nayyar’s Secret Acts Of Kindness Sparks Online Discussion

-

Video1 day ago

Video1 day agoFinancial Statement Analysis | Complete Chapter Revision in 10 Minutes | Class 12 Board exam 2026

-

Crypto World7 days ago

Crypto World7 days agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Crypto World5 days ago

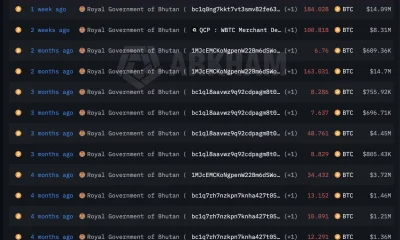

Crypto World5 days agoBhutan’s Bitcoin sales enter third straight week with $6.7M BTC offload

-

Tech10 hours ago

Tech10 hours agoRetro Rover: LT6502 Laptop Packs 8-Bit Power On The Go

-

Video7 days ago

Video7 days agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoThe strange Cambridgeshire cemetery that forbade church rectors from entering

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBarbeques Galore Enters Voluntary Administration

-

Business11 hours ago

Business11 hours agoTesla avoids California suspension after ending ‘autopilot’ marketing

-

Crypto World6 days ago

Crypto World6 days agoEthereum Price Struggles Below $2,000 Despite Entering Buy Zone

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoMan dies after entering floodwater during police pursuit

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoKalshi enters $9B sports insurance market with new brokerage deal