The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. Yan Chang Bennett – professorial lecturer at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and author of “American Policy Discourses on China: Implications from the Past and Predictions for the Future” (Cambridge Scholars 2024) – is the 454th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

Compare and contrast U.S. foreign policy narratives on China over time.

American narratives on China in U.S. foreign policy have evolved over centuries, shaped by enduring discourses rooted in historical perceptions. These narratives have oscillated between romanticized ideals of China as an exotic, redeemable civilization in the 19th century and more recent portrayals of China as a strategic rival.

Early American perceptions of China were shaped by the belief in a “special relationship,” in which the U.S. saw itself as responsible for China’s modernization and redemption – what I call the long 19th century discursive lens – which spanned from the founding of the United States to the early 1900s. China was then viewed as an ancient, exotic land with a seemingly vast market for American goods, despite that most Chinese had little interest or means to purchase them. Meanwhile, American missionaries and diplomats championed a paternalistic vision of guiding China toward Western-style progress. We see evidence of the long 19th century up to this century, when presidential administrations have initiated foreign policy that encourages China to change its fundamental nature and modify its behavior in adherence to the American system of rule-based order.

Not until 2017 did that worldview change. Today, we see a relationship of rivalry that can be termed strategic competition on the side of the United States. It seems that the United States has recognized China as a geopolitical opponent that has little regard for American values or for American leadership in the international system. The belief that engagement alone could modify state behavior has proven ineffective; sound foreign policy prioritizes national security interests over efforts to reshape external actor behavior.

Examine U.S. presidential China policy narratives.

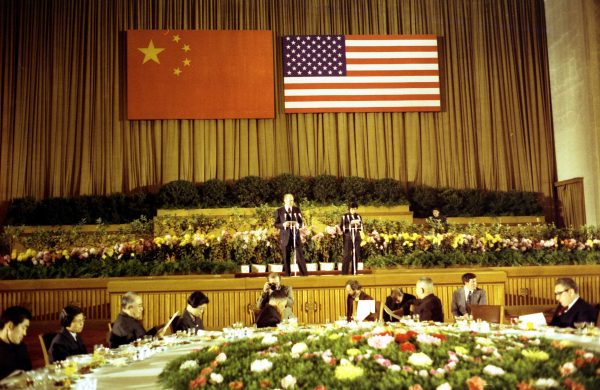

After a period of estrangement, the 1970s marked a shift with Nixon’s rapprochement, where the U.S. sought to reconnect with China to counterbalance the Soviet Union. The Carter administration further normalized relations, prioritizing engagement despite human rights concerns. This period revived narratives of China as an economic opportunity and a democratic transformation project.

The Clinton administration championed China’s integration into global markets, pushing for its WTO entry. Despite concerns over human rights violations, the administration resurrected 19th-century discourses, framing economic engagement as a catalyst for reform – both for the Chinese government and its people. The Bush and Obama administrations maintained engagement policies but began to recognize China’s increasing assertiveness.

Over the past decade, however, a fundamental shift has taken place, in which the U.S. has recognized the adversarial positioning China has taken and has adopted a more inward-focused policy that examines what are America’s priorities and interests rather than engaging in what can be deemed as trying to reprogram the interests of another nation.

Identify core messaging on China in American policy narratives in the 21st century.

Today, the core message is the assumption that China is seeking to replace U.S. leadership with its own as well as create a more beneficial world order that suits Beijing’s objectives. This has fueled rhetoric about decoupling from China while attempting to thwart China’s rise as a global power. While I largely agree, I would argue that China is not attempting a complete reordering. Therefore, American strategy should focus on identifying where China’s actions are detrimental to U.S. interests.

For example, China’s Belt and Road Initiative – offering loans and building infrastructure – is not inherently detrimental to American interests. Gaining control of ports and points of access in key theaters, however, is against American interests. China’s export-led economic strategy is also not necessarily problematic on its own. The issue lies with violation of intellectual property rights, monopolization of key industries through heavy state subsidies, and protectionist policies to build up Chinese industries at the expense and detriment of other national industries. These practices harm U.S. economic and strategic interests and should be the focus of American countermeasures.

Rather than trying to reform China, how can Washington leverage bilateral relations to advance U.S. national interests?

Rather than attempting to reform China, Washington should adopt a pragmatic, interest-driven approach that conditions engagement on tangible benefits for the United States. The U.S. should structure its policies unambiguously for its own interests rather than assuming China will cooperate out of goodwill or fundamentally change its governance system or culture with the right incentives. Recognizing that China operates strategically and in its own self-interest – sometimes aligning with U.S. objectives, but often not – is critical.

American expectations in trade, security, and geopolitical stability are nonnegotiable. The U.S. should deepen collaboration with Indo-Pacific allies and partners in furthering American interests. Both NATO and the EU have Indo-Pacific strategies and can be included in the broader coalition. At the same time, the U.S. must adopt a firm policy on China’s policies that are adversarial to American interests – such as military aggression, intellectual property theft, and cyber espionage, among other issues – that involves clear diplomatic consequences, targeted sanctions, and military deterrence where necessary. It is through avoiding appeasement and prioritizing integrated deterrence that the United States can put its national interests at the fore.

Assess the correlation between effective American policy discourse on China and statecraft.

The correlation between American policy discourse on China and statecraft lies in how narratives shape political realities and drive strategic decisions. Outdated and emotionally charged narratives can lead to policy missteps, whereas a more pragmatic and discourse-conscious approach could enhance the effectiveness of U.S. foreign policy.

My research suggests that for statecraft to be effective, nations must embrace a more strategic, evidence-driven narrative. For example, the Clinton administration relied on outdated discursive frameworks, relying heavily on the ideated notion that it was the duty of the United States to integrate China into a liberal international order because of their so-called special relationship. The current administration’s approach to China is much more pragmatically driven and addresses American core interests in mind.