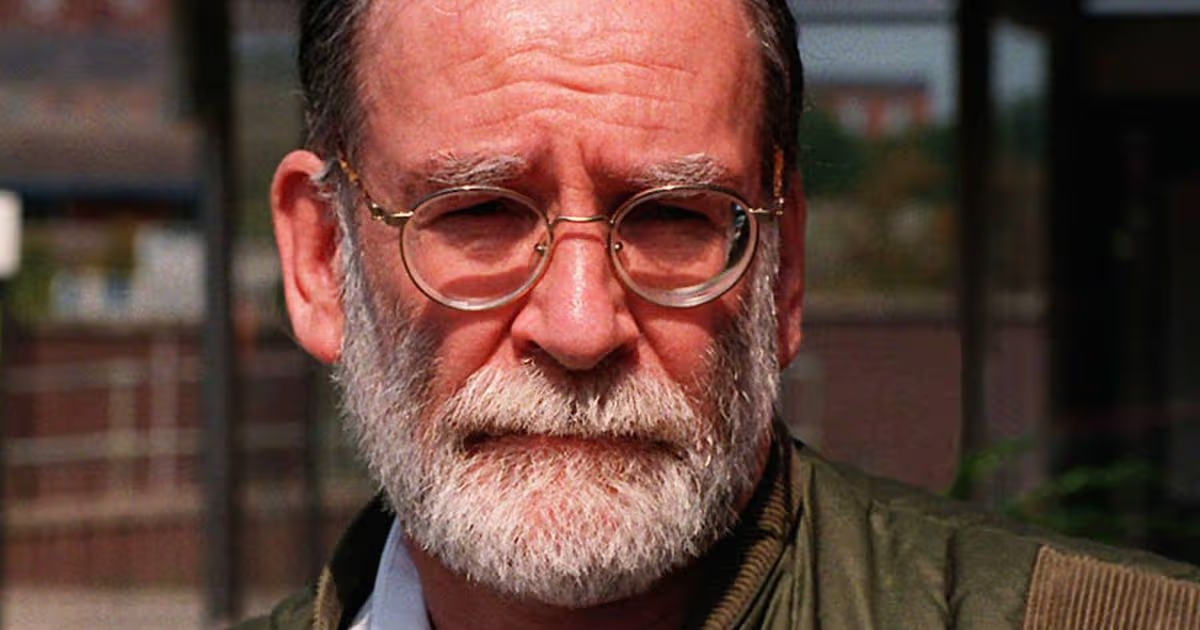

Serial killer Harold Shipman targeted his youngest victim, Peter Lewis, when the former popstar was at his most vulnerable, with the sick GP making a disturbing request of his devastated wife

One of the most prolific serial killers in criminal history, Dr Harold Shipman used his reputation as a “good doctor” to target those who’d trusted him to treat them in their hour of need.

The twisted GP often targeted older women in the small Greater Manchester town of Hyde, who were said to “adore” him, with an extraordinary 80 per cent of Shipman’s victims being female pensioners. Rather than providing them with care, Shipman instead injected fatal doses of poison into many of these patients, before callously pocketing money from their wills.

Shipman’s reign of terror finally came to an end in 1998 when he was arrested and subsequently convicted of murdering 15 of his patients, though the actual death toll is suspected to have reached the 250 mark over a staggering 30-year period. However, the sick medic didn’t only prey on the elderly, and, tragically, it’s suspected his youngest victim may have been just four years old.

READ MORE: UK’s worst serial killer Harold Shipman’s last words in horrifying personal letters before death

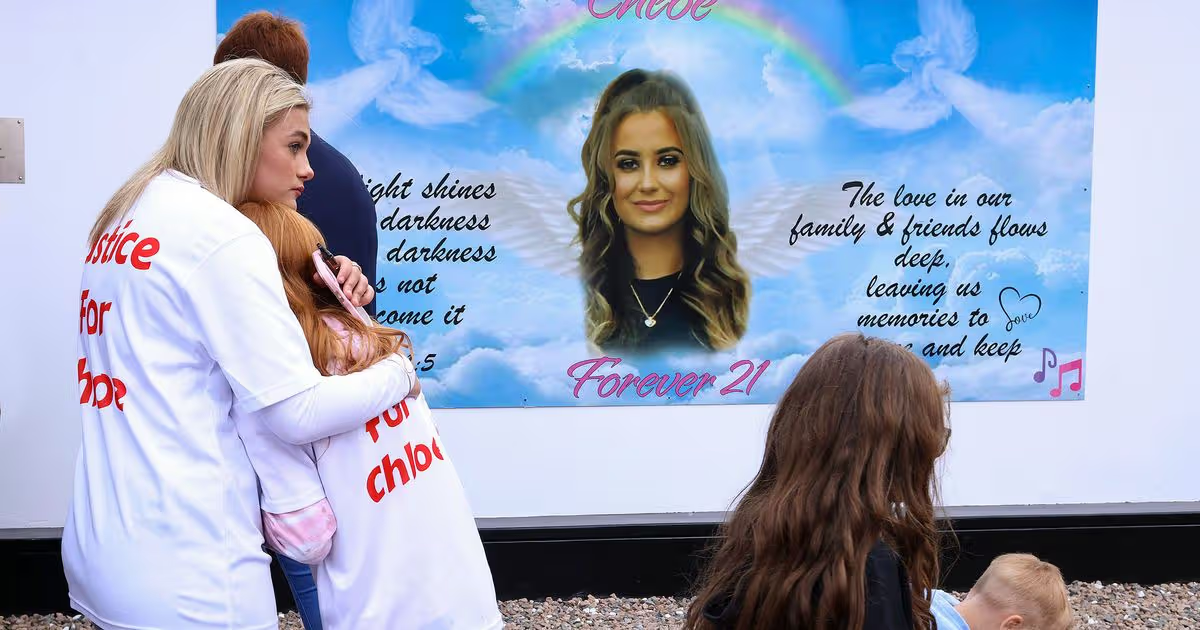

Indeed, Shipman’s youngest confirmed victim, Peter Lewis, was just 41 years old when the duplicitous monster set his sights on him, even cruelly getting the taxi driver’s wife to hold the needle as he injected the lethal dose of diamorphine.

While much younger than many of Shipman’s confirmed victims, Peter was at a particularly vulnerable stage in his life when the predator struck. In his younger years, Peter built a successful career as the frontman of pop group The Scorpions, with the group even securing a number one hit in Holland, toppling The Beatles from the chart summit.

He had tied the knot with his wife, Muriel, two years prior to his untimely demise, and the pair had relocated to Tameside, where their local GP was none other than Shipman. Shortly after settling in their new home, Peter started shedding weight at an alarming rate and sought medical advice, which was out of character for him. In a written testimony submitted to the Shipman Inquiry, Muriel recalled: “Pete was very much a man’s man. He was never ill. He took the view that going to the doctor was for softies,” she said.

“He had been the lead singer in a pop group and apparently had a number one hit in Holland. He even told me that he had knocked The Beatles off from the top spot. The band was called The Scorpions. Pete was always happy and was always singing. He always kept himself fit and didn’t put any weight on. I would describe him as typically northern.”

Sadly, it later emerged that Peter had been grappling with stomach cancer, a condition that Shipman had overlooked for half a year, instead diagnosing an ulcer. As Peter continued to weaken with each passing day, his worried wife Muriel had to assist him with one particular visit to the GP’s surgery, and it was here that they were taken aback by an inappropriate comment made by Shipman.

Muriel shared with the Manchester Evening News: “When we got into the doctor’s room, Shipman was washing his hands at the sink and turned to me saying, ‘Have you two got a season ticket?’” I didn’t believe what I had heard, so I said, ‘Sorry, what did you say?’ and he repeated it. As I was a little afraid of him, I simply laughed nervously. Until this occasion, I had always thought that he was a caring doctor.”

Eventually, Peter was referred to Manchester Royal Infirmary for surgery to determine the cause of his illness. He and his wife received the heartbreaking diagnosis that he had stomach cancer, which had already metastasised. Not long afterwards, Peter passed away at home, following a visit from Dr Shipman.

On the evening of New Year’s Eve 1985, Shipman was summoned to Peter and Muriel’s residence due to his deteriorating condition. Present in the bedroom were Shipman, Maureen, and her mother, Elsie Gee, when the doctor made a disturbing request.

He asked Peter’s wife to hold the injection needle steady in his patient’s arm. Muriel recalled: “As I was holding the needle in his arm, the blood flowed back into the barrel of the needle from his arm, and I had to go out of the room. I was very upset.

“I went back into the room and Shipman (had) one hand around Pete’s throat. He seemed to be squeezing Pete’s windpipe. I asked him what he was doing, and (he) said he was stopping him from swallowing his tongue. I wasn’t present when Pete died. I went into the lounge. I couldn’t stay till the end. I can remember, however, Shipman saying to Pete, ‘Come on, lad, give up. We’ve all had enough’. I gained the impression he was willing him to die.”

Muriel, unable to bear the sight of her husband in such agony, exited the room. However, when Muriel’s mother returned to the bedroom, she witnessed Shipman in a chilling stance. She recounted: “Dr Shipman was standing by the bed in front of Peter, holding a pillow in both hands. He was putting the pillow over Peter’s face. I shrieked, ‘What are you doing, man?’ and he put the pillow at the back of Peter’s neck.”

It would take another 13 years for doubts about Shipman to emerge, during which time he had been free to commit murder unchecked. Most of his victims were discovered sitting upright in a chair, fully clothed, appearing to have passed away from natural causes. In truth, Shipman had administered a fatal dose of morphine to them.

In March 1998, three months prior to his final act of murder, Deborah Massey from Frank Massey and Sons funeral parlour voiced concerns about the high number of deaths among Shipman’s patients. These concerns were relayed to Linda Reynolds from the Donneybrook Surgery, also located in Hyde, who then informed John Pollard, the coroner for the South Manchester District.

Linda also expressed worry about the number of cremation forms that Shipman had countersigned. The police were notified but lacked sufficient evidence to press charges, leaving Shipman free to claim the lives of three more patients.

Greater Manchester Police faced sharp criticism in the Shipman Inquiry after his conviction for allocating the investigation to inexperienced officers. However, doubts about the doctor persisted, and several months later, Hyde taxi driver John Shaw approached police, claiming he suspected Shipman had murdered 21 of his patients.

Ultimately, Shipman would seal his own fate through a catastrophic error during the killing of his last victim, Kathleen Grundy. The 81-year-old was discovered dead at her home on June 24, 1998. Shipman had been the final person to see her alive and documented “old age” as her cause of death on the death certificate.

Yet her daughter, Angela Woodruff, a solicitor, sensed something was deeply amiss when her solicitor, Brian Burgess, contacted her regarding her mother’s will. Kathleen had disinherited her own children and instead bequeathed her entire £386,000 estate to Shipman.

It read: “I give all my estate, money and house to my doctor. My family are not in need and I want to reward him for all the care he has given to me and the people of Hyde.” The document reached her solicitor’s office on the day of her death, accompanied by a letter that had been typed on the identical typewriter as her will and bore Kathleen’s signature.

The letter said: “Dear Sir, I enclose a copy of my will. I think it is clear in intent. I wish Dr Shipman to benefit by having my estate, but if he dies or cannot accept it, then the estate goes to my daughter. I would like you to be the executor of the will. I intend to make an appointment to discuss this and my will in the near future.”

Mr Burgess advised Angela to report the matter to the police, who subsequently launched an investigation and exhumed Kathleen’s body. Medical heroin traces were discovered in his system, a substance often used for pain management in terminal cancer patients.

Shipman attempted to justify this by alleging that Kathleen was an addict, presenting detectives with notes he had recorded on her digital medical files. However, upon inspection of his computer, it was revealed that these notes had been added posthumously, leading to Shipman’s arrest on September 7 1998.

He had made one final mistake – the falsified will had been typed on a Brother typewriter, which Shipman owned, and he had also left a fingerprint on the document. Police were convinced that Kathleen wasn’t his only victim and compiled a list of 15 potential murder victims for whom Shipman had signed death certificates.

A recurring pattern soon became apparent: high doses of diamorphine, or heroin, followed by his signing the death certificates and fabricating health complications. On January 31, 2000, Shipman was convicted of 15 counts of murder and one count of forgery. He received a life sentence. On January 13, 2004, Shipman was found hanged in his cell at Wakefield Prison, West Yorkshire. The Shipman Inquiry, conducted two years after his conviction, concluded that he had killed at least 215 of his patients.

Dame Janet Smith, who presided over the inquiry, believes he was responsible for 250 deaths. Shipman’s atrocities sparked sweeping reforms across the medical profession. Single-handed GP surgeries have become increasingly rare as a result.

Do you have a story to share? Email me at julia.banim@reachplc.com

READ MORE: Dad-of-four with ‘normal life’ murders up to 215 people as ‘Britain’s worst killer’

![Heathrow has said passenger numbers were 60% lower in November than before the coronavirus pandemic and there were “high cancellations” among business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas for Christmas as Omicron spreads. The UK’s largest airport said the government’s travel restrictions had dealt a fresh blow to travel confidence and predicted it was likely to take several years for passenger numbers to return to pre-pandemic levels. This week ministers said passengers arriving in the UK would have to take a pre-departure Covid test, as well as a post-flight test, because of fears about the spread of the new variant. “[The] high level of cancellations by business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas because of pre-departure testing shows the potential harm to the economy of travel restrictions,” the airport said in an update. Heathrow said the drop in traveller confidence owing to the new travel restrictions had negated the benefit of reopening the all-important corridor to North America for business and holiday travel last month. Eleven African countries have been added to the government’s red list, requiring travellers to quarantine before reuniting with families. “By allowing Brits to isolate at home, ministers can make sure they are reunited with their loved ones this Christmas,” said John Holland-Kaye, the chief executive of Heathrow. “It would send a strong signal that restrictions on travel will be removed as soon as safely possible to give passengers the confidence to book for 2022, opening up thousands of new jobs for local people at Heathrow. Let’s reunite families for Christmas.” Heathrow said that if the government could safely signal that restrictions would be lifted soon, then employers at Heathrow would have the confidence to hire thousands of staff in anticipation of a boost in business next summer. The airport is expecting a slow start to 2022, finishing next year with about 45 million passengers – just over half of pre-pandemic levels. This week Tui, Europe’s largest package holiday operator, said it expected bookings for next summer to bounce back to 2019 levels. However, Heathrow said on Friday not to expect the aviation industry to recover for several years. “We do not expect that international travel will recover to 2019 levels until at least all travel restrictions (including testing) are removed from all the markets that we serve, at both ends of the route, and there is no risk of new restrictions, such as quarantine, being imposed,” the airport said.](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/shutterstock_1100012546-scaled-400x240.jpg)

![Heathrow has said passenger numbers were 60% lower in November than before the coronavirus pandemic and there were “high cancellations” among business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas for Christmas as Omicron spreads. The UK’s largest airport said the government’s travel restrictions had dealt a fresh blow to travel confidence and predicted it was likely to take several years for passenger numbers to return to pre-pandemic levels. This week ministers said passengers arriving in the UK would have to take a pre-departure Covid test, as well as a post-flight test, because of fears about the spread of the new variant. “[The] high level of cancellations by business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas because of pre-departure testing shows the potential harm to the economy of travel restrictions,” the airport said in an update. Heathrow said the drop in traveller confidence owing to the new travel restrictions had negated the benefit of reopening the all-important corridor to North America for business and holiday travel last month. Eleven African countries have been added to the government’s red list, requiring travellers to quarantine before reuniting with families. “By allowing Brits to isolate at home, ministers can make sure they are reunited with their loved ones this Christmas,” said John Holland-Kaye, the chief executive of Heathrow. “It would send a strong signal that restrictions on travel will be removed as soon as safely possible to give passengers the confidence to book for 2022, opening up thousands of new jobs for local people at Heathrow. Let’s reunite families for Christmas.” Heathrow said that if the government could safely signal that restrictions would be lifted soon, then employers at Heathrow would have the confidence to hire thousands of staff in anticipation of a boost in business next summer. The airport is expecting a slow start to 2022, finishing next year with about 45 million passengers – just over half of pre-pandemic levels. This week Tui, Europe’s largest package holiday operator, said it expected bookings for next summer to bounce back to 2019 levels. However, Heathrow said on Friday not to expect the aviation industry to recover for several years. “We do not expect that international travel will recover to 2019 levels until at least all travel restrictions (including testing) are removed from all the markets that we serve, at both ends of the route, and there is no risk of new restrictions, such as quarantine, being imposed,” the airport said.](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/shutterstock_1100012546-scaled-80x80.jpg)