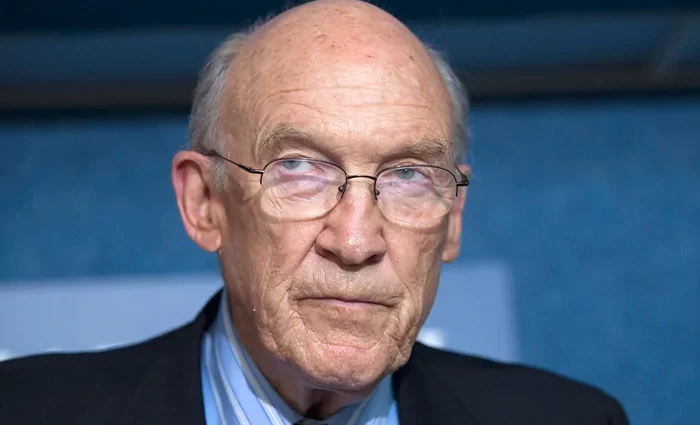

Some politicians glide into history on the wings of charisma or the heft of legislation. Others barrel in like a Wyoming windstorm, leaving a trail of quips, quarrels, and quiet victories. Alan K. Simpson, the towering Republican senator from the Equality State who died this month at 93 in his beloved Cody, Wyoming, was the latter — a lanky, sharp-tongued maverick whose three terms in the Senate from 1979 to 1997 were as much a testament to his grit as to his gift for finding common ground in a partisan swamp. If politics is theater, Simpson played the cowboy sage: part John Wayne, part Will Rogers, with a dash of mischief that could charm a rattlesnake or rile a room. Simpson’s life was a sprawling Western epic — rough-hewn, irreverent, and improbably tender.

Alan Kooi Simpson was born on Sept. 2, 1931, in Denver, but Cody claimed him as its own. His middle name honored his maternal grandfather, a Dutch immigrant, while his political DNA came straight from his father, Milward Simpson, a former Wyoming governor and U.S. senator. Young Al was no stranger to trouble — shooting guns, vandalizing property, and catching the eye of local lawmen as a teenager. “I was a hellion,” he’d later admit with a grin, “but I grew out of it.” The Army straightened him out from 1954 to 1956, and he earned a law degree from the University of Wyoming in 1958. He joined his father’s law practice, a stepping stone to a life in public service that began in earnest when he won a seat in the Wyoming House of Representatives in 1964.

Simpson’s leap to the U.S. Senate in 1978 was less a calculated climb than a natural extension of his roots. At 6-foot-7, with size 15 shoes and a voice that boomed like a prairie thunderstorm, he cut an unforgettable figure in Washington. His 18-year tenure coincided with the Republican Party’s Reagan-fueled resurgence, and as Senate whip from 1985 to 1995, he wrangled GOP votes with a blend of humor and hard-nosed pragmatism. “We have two political parties in this country,” he once quipped, “the Stupid Party and the Evil Party. I belong to the Stupid Party.” Yet beneath the barbs lay a serious legislator. His crowning achievement, the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, was a bipartisan beast he likened to “giving dry birth to a porcupine” — a slog that legalized millions while tightening borders, reflecting his knack for balancing principle with compromise.

Simpson’s conservatism was never cookie-cutter. He championed Supreme Court justice nominees such as Robert Bork, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas, yet also supported legal abortion, gay rights, and immigration reform, stances that rankled party purists — “I’m the original RINO,” he once joked — even as he drew the ire of women’s groups, environmentalists, and the press. He called environmental lobbyists “super-greenies” and “bug-eyed zealots,” delighting in poking sacred cows. But his wit was a bridge, not a wall. Friendships with Democrats such as Norman Mineta, whom he met in the Boy Scouts during Mineta’s internment at Wyoming’s Heart Mountain camp in World War II, showed a humanity that transcended ideology. That bond later fueled Simpson’s advocacy for the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, honoring a dark chapter of American history.

After leaving the Senate in 1997, Simpson didn’t fade into the sagebrush. He taught at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and the University of Wyoming, skewering political pieties with a relish that kept students on their toes. One lecture famously began with him tossing a fake grenade to jolt the room awake. In 2010, he co-chaired then-President Barack Obama’s debt reduction commission with Erskine Bowles, pushing a $4 trillion austerity plan that Congress ignored but that cemented his elder-statesman cred. Ever the gadfly, he’d lament Washington’s gridlock: “It’s like watching a herd of cows stare at a new gate.” His humor never dulled: “I’m too old to count the candles,” he’d say, “but young enough to make bad decisions.” In 2022, then-President Joe Biden, another Senate pal from the old days, awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, a nod to a career that defied easy labels and a friendship forged over decades of late-night Senate debates.

Simpson’s final act unfolded in Cody, where he’d lived since childhood, surrounded by family — his wife Ann, whom he married in 1954, and their three children, William, Colin, and Susan. A December 2024 hip injury led to an amputation, but his spirit held until the end. “Al went to heaven on a moonbeam,” his wife told a friend, noting the full moon over Cody that night. It’s a fitting image for a man who lived large, loved Wyoming fiercely, and left Washington a little less dour than he found it. In an era of shouting matches, Simpson’s voice, gruff, funny, and unafraid, reminds us that politics, like life, is best navigated with a steady hand, a sharp tongue, and a heart as wide as the plains.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the author, most recently, of Soloveitchik’s Children: Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, Jonathan Sacks, and the Future of Jewish Theology in America.