Reporting Highlights

- A First for “The First 48”: The exoneration of Edgar Barrientos-Quintana may be the first in the country related directly to the involvement of the television show.

- Partnerships Soured: Multiple cities ended their relationships with “The First 48” after problems, including Minneapolis; Miami; Detroit; Mobile, Alabama; and Memphis, Tennessee.

- Criticism From All Sides: Complaints about the show’s impact on criminal prosecutions have come from prosecutors and defense lawyers, as well as judges and city officials.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

Eleven days after 18-year-old Jesse Mickelson was gunned down in a South Minneapolis alley, homicide detectives returned to the home where Mickelson had been playing football moments before his murder. The detectives had good news to share, so Mickelson’s family and friends squeezed around the dining room table to hear it.

“Yes,” someone said. “Thank you.”

Dale and his partner, Sgt. Christopher Gaiters, told the family they had arrested a suspect, a man witnesses said they saw firing from the back seat of a white Dodge Intrepid as it rolled down the alley. His name was Edgar Barrientos-Quintana, and the police had the 25-year-old in custody.

As the family members hugged one another and cried, Mickelson’s father stuck his hand out to Gaiters, then wrapped the detective in a hug.

“Thanks a lot, man,” he said quietly. “Thanks a lot.”

The scene in the grieving family’s dining room was captured in October 2008 by cameras for the A&E true crime reality television series “The First 48.” The premise of the show, as explained by a deep-voiced narrator, is that homicide detectives’ “chance of solving a murder is cut in half if they don’t get a lead within the first 48 hours.” In each episode of the program, which debuted in 2004 and is currently in its 27th season, camera crews follow along with police as they work to beat a clock that counts down in the corner of the screen.

The episode, titled “Drive-By,” tracked the detectives from the moment Mickelson’s family dialed 911 to the arrest of Barrientos-Quintana. Under moody, dark music punctuated by dramatic sound effects, Dale and Gaiters determined that Mickelson, a lanky high school senior with icy blue eyes, was “a pretty good kid” and the unintentional victim of a gang-related drive-by shooting. Based on interviews with witnesses, their faces blurred and voices distorted for TV, the detectives pieced together that “Smokey,” a nickname for Barrientos-Quintana recorded in a police database, was the shooter.

The episode aired in April 2009, about a month before Barrientos-Quintana went to trial.

In court, the case against Barrientos-Quintana that Hennepin County prosecutors presented built on the clean, conclusive narrative of the episode. Witnesses from rival gang cliques testified they either were in the car with Barrientos-Quintana when the crime occurred or saw him shooting at them.

The prosecutors also told jurors that Barrientos-Quintana’s alibi, that he’d been with his girlfriend at a grocery store across town before the murder, still allowed him time to get to the crime scene.

After a jury found Barrientos-Quintana guilty, reruns of the episode ended with a title card that read, “Edgar ‘Smokey’ Barrientos was subsequently convicted of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life without parole.”

Sixteen years later, that tidy narrative unraveled. Last year, the Minnesota attorney general’s Conviction Review Unit released a 180-page report concluding that Barrientos-Quintana’s conviction “lacks integrity” and ought to be vacated. In November, Barrientos-Quintana — who always maintained his innocence and was never linked to the crime by any physical evidence — walked out of prison.

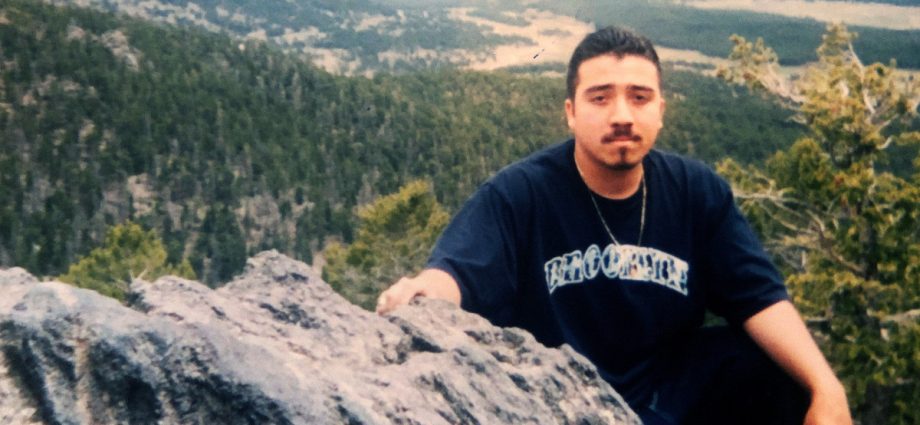

At a press conference led by Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty, who made the decision to dismiss the charges, Barrientos-Quintana shifted back and forth on his feet and smiled nervously, the grey in his beard a notable difference from his appearance in “The First 48” episode.

“Happy to be out here,” was all that he offered to the reporters asking how he felt. “It’s the best week. And more to come.” Barrientos-Quintana, through his lawyers, declined an interview request.

Credit:

Amy Anderson Photography/Courtesy of the Great North Innocence Project

The Conviction Review Unit report that ultimately convinced both Moriarty’s office and a judge that Barrientos-Quintana should be freed outlined dozens of issues with the investigation and trial, many of them hallmarks of wrongful convictions. Long, coercive interrogations. Improper use of lineup photos.

Both the report and the judge’s order also highlighted one unique issue: the role of “The First 48.”

“In the episode, events happened out of order, and Sgts. Dale and Gaiters staged scenes for the producers that were not a part of the investigation,” wrote Judge John R. McBride. “What is more, the episode failed to include other, actual portions of the investigation, painting a wholly inaccurate picture of how the MPD investigation unfolded.”

Conviction Review Unit attorneys concluded that police and prosecutors became locked into a narrative they did not deviate from. In essence, the unit alleged, instead of the case shaping the show, the show shaped the case.

“They said, ‘We got the right guy. We got him,’ before they knew or really looked into the existence of Edgar’s alibi,” said Anna McGinn, an attorney for the Great North Innocence Project who represented Barrientos-Quintana. “It’s on TV. I mean, that’s problematic.”

Barrientos-Quintana’s exoneration may be the first in the country related to the “The First 48,” but it is not the first time the program has found itself embroiled in controversy, though not necessarily because of its conduct. In 2010, for instance, “The First 48” was filming when a Detroit police SWAT-style team raided an apartment and an officer shot and killed 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones. In Miami, a man featured on the show as the prime suspect in a 2009 double murder sat in jail for 19 months before the police finally determined he wasn’t responsible. In both cases, subsequent lawsuits accused the police of shoddy investigations and hasty decision-making in the service of creating good TV. Both cases ended in settlements — $8.25 million in Detroit — paid out by the cities, not “The First 48.”

“No one cared that my boy was killed, and the cops just rushed it for a damn show,” the father of one of the double murder victims told the Miami New Times.

Prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys and city officials across the country have bemoaned their police departments’ decision to allow the show into active crime scenes to film officers investigating sensitive homicide cases. It’s even been raised as an issue by an attorney who represents a death row inmate in Tennessee.

“I wish that the city would never contract with ‘The First 48,’” remarked one New Orleans judge in 2015 after the show was accused by defense lawyers of lying about deleting raw footage of a triple murder investigation. “I hope in the future they would think through that.”

“The First 48,” like similar programs such as “Cops” and “Live PD,” is sometimes derided as “copaganda,” pro-law-enforcement entertainment that poses as documentary. But it’s popular enough that A&E frequently programs hours of reruns back to back. Fans discuss favorite episodes on a busy, dedicated Reddit channel.

While other police reality shows have also received negative attention and have been canceled after high-profile incidents, “The First 48” has largely avoided broader public scrutiny. Over the past two decades, the cities of Memphis, Tennessee; New Orleans; Detroit; and Miami have ended their relationships with “The First 48” after the show’s presence snarled prosecutions or otherwise created problems.

Those severed partnerships seem to have done little to slow production of the show. Kirkstall Road Enterprises, the subsidiary of ITV that produces the show, simply moved on; the most recently released episodes were filmed in Tulsa, Oklahoma; Gwinnett County, Georgia; and Mobile, Alabama, although Mobile did not renew its contract in 2023 after complaints from defense attorneys.

Neither ITV nor ITV America responded to numerous requests for comment or to a detailed list of questions. A spokesperson for A&E Network declined to comment.

Moriarty was Minnesota’s chief public defender the last time she tangled with “The First 48” on behalf of clients in 2016, and she is still dealing with fallout from the show in her first term as Hennepin County attorney.

“They are allowed to continue to do probably a great deal of damage without being discovered, without really having any consequences,” said Moriarty. “Hopefully, places where this is happening, the city, city council, mayor, whatever, could put a stop to it, and cities where it isn’t happening, they could be prepared when ‘First 48’ comes to their town.”

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/Propublica

“A False Narrative”

When Assistant Attorney General Carrie Sperling, the director of the Minnesota Conviction Review Unit, began her reinvestigation of the Barrientos-Quintana conviction, one of the first things she did was watch the episode of “The First 48” that featured his case. She was immediately alarmed.

“It’s a false narrative,” she said. “Investigators are just misrepresenting details about the case on TV.”

Barrientos-Quintana began reaching out for help with his conviction almost as soon as he got to prison. In 2011, he became one of a handful of inmates whose cases were accepted for review by the Great North Innocence Project, a nonprofit that investigates possible wrongful convictions in Minnesota and the Dakotas.

But his appeals went nowhere and, according to McGinn, the case was essentially dormant until the Minnesota attorney general’s office launched its Conviction Review Unit in 2021. Because the unit operates within a state law enforcement agency, its investigators had access to material Barrientos-Quintana’s lawyers said they never saw.

Sperling wanted to understand why detectives zeroed in on Barrientos-Quintana and left other potential suspects to the side. In Gaiters and Dale’s theory of the crime, Barrientos-Quintana was a member of the Sureños 13 gang and had recently gotten into a fight with a member of a rival clique called South Side Raza. The leader of that clique, nicknamed Puppet, lived across the alley from Mickelson’s house and may also have been seeing the same girl as Barrientos-Quintana.

Early on in the investigation, a student at Mickelson’s high school told police she’d heard that the shooter was named “either Smokey or Sharky.” Dale and Gaiters identified a 16-year-old boy known as Sharky, but for reasons the Conviction Review Unit report said are “not clear,” detectives decided that Sharky was an accomplice, while Barrientos-Quintana, or Smokey, was the shooter.

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/Propublica

In the course of listening to hours of Gaiters and Dale’s original interviews with witnesses, Sperling was struck by how differently “The First 48” portrayed those conversations. According to the Conviction Review Unit report, about a half-dozen witnesses, some of them Mickelson’s friends and family and some from Puppet’s side of the alley, all agreed on one thing: The shooter was bald, “shiny bald” even. That fact is never mentioned in the episode, and footage of Barrientos-Quintana’s arrest and interrogation shows him with a full head of black hair.

“They show the video footage of Edgar being arrested at work, and he’s clearly not bald,” said McGinn. “That is an intentional omission, I believe, and that’s very misleading.”

At the time Mickelson was shot and killed, Barrientos-Quintana had an arrest record and had convictions for driving offenses and misdemeanor property damage, according to court records. He’d been affiliated with the Sureños 13 gang, but he told detectives he’d left that life behind and was working at a computer warehouse.

More importantly, perhaps, he told police he was with his girlfriend in a suburb on the other side of town the day of the shooting. In “The First 48,” Dale makes a phone call to a “family friend” of Barrientos-Quintana’s, a conversation that Dale implies has blown the alibi apart, leaving a four-hour window when Barrientos-Quintana could have committed the murder.

In reality, the 15-year-old girl Barrientos-Quintana was with on the day of the shooting was being questioned at the same time in a separate room. She told detectives repeatedly that Barrientos-Quintana had been with her the whole day at her home. When investigators suggested the pair couldn’t have spent the entire day indoors, the girl offered that at one point they’d left to go to the grocery store but had come straight back.

Toward the end of the episode, a distraught Barrientos-Quintana tells Dale, “Right now, I just want to get myself a lawyer.” In the episode, the interrogation stops, as if Barrientos-Quintana’s constitutional right to an attorney was immediately honored. But according to the Conviction Review Unit report, Gaiters and Dale ignored his requests for a lawyer and, at one point, a third officer told Barrientos-Quintana that the detectives would not listen to him if he kept asking for representation.

“The First 48” cameras were long gone when, months later, Gaiters and Dale obtained security camera footage of Barrientos-Quintana and the girl at the grocery store. The footage shows the pair together, smiling and walking toward the store’s exit, just before 6:20 p.m. The shooting took place roughly 33 minutes later and about 14 miles away, creating a narrow window of time for Barrientos-Quintana to part ways with the girl, change clothes and meet up with his supposed accomplices before witnesses first spotted the Dodge Intrepid behind the Mickelson home.

Credit:

Obtained from the Great North Innocence Project by ProPublica

“The First 48” episode about the case aired about two months after this new piece of evidence came to light. There is no mention of it in the program.

The security footage was far from prosecutors’ only challenge heading into the May 2009 trial. In preparation, according to the Conviction Review Unit report, prosecutors Susan Crumb and Hilary Caligiuri learned that Dale had been “playacting for a reality TV crew” and the defense might be able to use that revelation to undermine the testimony of Dale or Gaiters.

In addition, prosecutors told their supervisors in a memo that the show had edited footage of the investigation out of chronological order, generating an inaccurate depiction of what happened. As a result, only Gaiters testified.

Because the episode aired before trial and a key witness watched it, Crumb and Caligiuri scuttled plans to ask him to identify Barrientos-Quintana in court. All of this was revealed in the memo Caligiuri and Crumb wrote to their supervisors immediately following the trial to express their concerns about the city working with “The First 48,” the contents of which were never shared with Barrientos-Quintana’s defense attorneys.

Caligiuri, who is now a judge, is precluded from speaking to the press by the Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct, according to a court spokesperson. Crumb, in an email response to questions from ProPublica, took issue with many of the characterizations in the Conviction Review Unit report but agreed that “The First 48” had been a problem.

She said the producers’ scripting for Dale was “innocuous” but could have caused problems for prosecutors in cross-examination. And she said a young witness became so afraid after seeing clips of the episode that he ran away from home and, even after police arrested him, refused to testify for prosecutors.

“Contrary to the CRU’s assertion, Barrientos-Quintana was not wrongfully convicted, as the Minnesota Supreme Court confirmed and as an unbiased review of the file and trial record would confirm,” Crumb, who is retired, said in the email.

“The filming of the First 48 created problems the defense used to try to sow doubt regarding the Defendant’s guilt,” she added. “If there was any ‘hindrance to the administration of justice’ in this case, it was only to the detriment of the prosecution, not the defense.”

At trial, Gaiters testified that when he re-created the route from the grocery store to the crime scene, it took 28 minutes, enough time for Barrientos-Quintana to commit the shooting with just minutes to spare. But that did not account for how the girl he was with got home, nor did it square with the claim by Sharky, who was by now one of the prosecution’s chief witnesses, that after he met up with Barrientos-Quintana in a park near Mickelson’s home, they “cruised around,” adding several minutes to the timeline. A private investigator hired by the defense testified that his re-creation of the route took him 33 minutes.

The man identified as Sharky could not be reached for comment.

Dale, who retired from the Minneapolis Police Department in 2023, declined to comment. Gaiters rose through the ranks of the department to become assistant chief of community trust. Through a department spokesperson, Gaiters declined to comment.

The Police Department did not respond to a detailed list of questions other than to confirm that it ended its relationship with “The First 48” in 2016. But ahead of Barrientos-Quintana’s release, Chief Brian O’Hara said publicly he supported Dale and Gaiters’ original investigation and was “concerned that a convicted killer will be set free based only upon a reinterpretation of old evidence rather than the existence of any new facts.”

The jury struggled to come to a verdict, at one point close to deadlocking with three members unwilling to convict, according to the Conviction Review Unit report. But after being allowed to review Sharky’s testimony, they found Barrientos-Quintana guilty. He was sentenced to life without parole.

In his order vacating the conviction, McBride wrote that the “colossal failures” and “ineptitude” of Barrientos-Quintana’s original lawyers were — on their own — grounds for a new trial. The Conviction Review Unit report also criticized his lawyers, saying they repeatedly failed to challenge many aspects of the prosecution’s case as well as Gaiters’ testimony.

Messages left for Barrientos-Quintana’s four pretrial and trial attorneys were not returned. According to the Conviction Review Unit report, in the years following the trial, one of the lawyers was disbarred, a second had his law license suspended for unethical behavior and a third, who dropped out of the case just before trial, was convicted of swindling a client. The fourth lawyer, the report said, has a clean disciplinary record but had passed the Minnesota bar just a month before trial.

According to McGinn, being featured on “The First 48” gave Barrientos-Quintana an added — and unwelcome — notoriety in prison. She said that although he is now free, he is distraught that, until recently, “The First 48” episode was still available in reruns on A&E and other channels, and was available for streaming.

“There’s been no statement that says, ‘Hey, we retract this,’ or ‘This is an inaccurate depiction of what actually happened that night that Jesse was killed,’” said McGinn.

A&E said last week that the episode is not currently available.

Journalism or Entertainment?

Kirkstall Road Enterprises, which was once known as Granada Entertainment USA and Granada America, enters into agreements with police departments sometimes without the knowledge or approval of other departments in city government. That’s one reason prosecutors and other officials have felt blindsided by the problems “The First 48” has caused them.

After 7-year-old Stanley-Jones was shot and killed by police in 2010 as “The First 48” cameras rolled, then-Detroit Mayor Dave Bing said he was shocked to find out that his chief of police had agreed to embed a reality television crew with officers.

“That’s the end of that,” he reportedly told the chief before banning the practice.

Minneapolis police signed agreements to allow the program to film from 2007 to 2009 and then signed a new deal with the program in 2014. But the city ended its relationship with the show two years later, after legal fighting over the show’s raw footage delayed court proceedings and then-Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman slammed the program.

“‘The First 48’ is an entertainment device. It’s not a device seeking truth or justice,” Freeman said at the time. “It gets in the way of us doing our job, the defense doing their job. We wish the police would never have signed up for this.”

Freeman, since retired, did not respond to requests for comment.

Copies of contracts between police departments and Kirkstall Road Enterprises reviewed by ProPublica give producers broad access to investigations so long as they do not interfere with officers’ work. They also have creative control over the final product, though departments are allowed to review an episode before it airs. Police departments can request changes, but producers are not obligated to make them.

The contracts also show that Kirkstall Road Enterprises does not provide departments with any monetary compensation. Before ending its relationship with the show after nine years, the chief of the Miami police requested that the production company donate $10,000 for every Miami episode to the department’s charitable youth athletic league in order to continue filming. The show did not accept those terms.

There are benefits to law enforcement, like positive publicity and recruitment potential. Alabama police officials in Birmingham and Mobile said they believed the show helped them solve more murders.

After New Orleans ended its contract with the show, the head of the police union, the Police Association of New Orleans, told a reporter, “At a time when community relations are so fragile, locally and nationally, it was of enormous benefit to everyone to have an avenue open for the public to see what we do and how we do it.”

Although the New Orleans police ended their relationship with “The First 48” in 2016, they’re now participating in a new A&E program called “Homicide Squad New Orleans,” which began airing episodes this year.

Officers featured on “The First 48” also sometimes enjoy a degree of local celebrity. One Dallas detective became so well known that a suspect recognized him as soon as he walked into an interrogation room. A detective in Memphis, according to court filings, carried photos of herself to sign for fans of the program. Fan accounts on Instagram wish their favorite detectives happy birthday and track their promotions.

The biggest issue with the show for defense attorneys and prosecutors is access to the raw footage, especially in the days before body-worn cameras — footage that may not make the ultimate “The First 48” episode but could capture important conversations and some of the earliest images of the crime scene.

“It’s incredibly important for prosecutors and defense lawyers to have video of anything that pertains to the scene or witnesses,” said Moriarty.

But according to court documents, Kirkstall Road Enterprises instructs all of its field producers — employees “who act as producer, cameraman and sound technician all rolled into one,” according to an affidavit provided by the show’s senior executive producer — never to share raw footage with law enforcement. It is also the show’s practice to decline all subpoenas for footage using First Amendment arguments, citing state shield laws that protect journalists from turning over their reporting material. Prosecutors and defense lawyers have struggled to convince judges that the needs of the state or the defendants override those protections. The show also claims it is routine practice to destroy all raw footage after a completed episode is delivered to A&E.

But reporters and others say it’s important to protect their work from being seized by police and prosecutors, as well as to maintain their credibility and independence. In short, they don’t want to become, or even be seen as, arms of government. But Moriarty said she believes that, by embedding with police during an active investigation, “The First 48” occupies a gray area.

In 2016, when Freeman, the former Hennepin county attorney, was trying to get footage from “The First 48” in ongoing cases, he said that he found the show’s refusal to provide it problematic.

“If ‘The First 48’ tries to pull the mantle of the First Amendment around this and be sanctimonious — you know something, defendants have rights,” he said at the time. “And people want the truth.”

Later that year, the contract between “The First 48” and the city of Minneapolis expired and was not renewed. A spokesperson for the Minneapolis Police Department confirmed the end of the relationship and added that “MPD has transitioned away from formal contractual agreements with media partners and now engages with them on a case-by-case basis.”

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/Propublica

A Pivotal Scene

Looking back on the “The First 48” episode now, the Conviction Review Unit’s Sperling said one part bothers her most: the oddly performative scene with Mickelson’s family jammed around the dining room table with Gaiters and Dale.

Tina Rosebear, Mickelson’s 44-year-old half-sister, was present the night of the detectives’ visit, though she barely registered that a camera crew was filming; she was still in shock over the murder.

Rosebear, a personal care assistant and gas station clerk, took on a lot of responsibility in her family at an early age. She was more than an older sister to Mickelson, becoming his primary caregiver when he was 8 years old.

“I know that’s your son,” she remembers telling their mother when Mickelson died, “but that’s my baby.”

Before “The First 48” became more widely available, Rosebear kept multiple copies of the episode on DVD, labeled in Sharpie with the date of his death. She’s watched the episode dozens of times. Although she acknowledges some might find it strange, she said she gets a sense of comfort seeing the blurred shots of her brother’s body — the footage captured one of the last times she saw him in his “human form,” as she puts it, before he was zipped in a body bag and later reduced to the box of ashes she keeps on her bookshelf.

But Rosebear said it only took until Page 40 of the Conviction Review Unit report for her to realize that she and her family had been misled by the police — and also by “The First 48.”

“I feel like it was all done for the TV show,” she said. “But that was unfair to him, and that was unfair to us.”

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/Propublica

Rosebear attended the press conference announcing Barrientos-Quintana’s release. She’d seen him in court at his trial, but that was their first real meeting. She apologized to him on behalf of her family and gave him a hug.

“He gets to be with his family now, and now we can try to continue to heal with the loss of my brother now that everything was just ripped back open,” she told reporters.

The Conviction Review Unit report not only cleared Barrientos-Quintana, but it contained information that could theoretically point to the real gunman. But Rosebear isn’t sure she could handle going through the whole process again — another arrest, another trial.

Once a fan of “The First 48,” Rosebear said she now hopes that the program is shut down.

“Could they have did a better job if the TV show wasn’t involved? Probably,” she said. “Nobody knows now. Because it’s too late.”

Mariam Elba contributed research. Design and development by Zisiga Mukulu.