Uncategorized

The US must stand up to Putin, now

Russia, a power motivated by imperial conquest, continues to wage war on Ukraine, challenging the United States-led democratic international order. Too many in Washington underestimate Russia’s threat, or are hesitant to confront it. Across administrations — from Obama to Biden to Trump — there have been repeated calls for accommodation, for de-escalation, for “peace.” Such calls are often framed as servants of pragmatic strategy.

Moral certainty, we’re told, is a sacrifice made in the name of self-interest. China is the bigger threat. Russia is a sideshow. Some “realists” and “isolationists” argue that Moscow, if handled right, might even help counter China. But this overlooks the obvious: Russia’s strategic aim — like China’s — is to weaken U.S. power. Moscow is not a potential asset, but rather a potent adversary.

In Ukraine, Russian forces fight for months, and at the cost of tens of thousands of soldiers, just to take towns the size of a small city park. They rely on Iranian drones, North Korean soldiers, and Russian convicts. The economy is increasingly strained under sanctions. The Kremlin leadership is paranoid. The population is exhausted. Put simply, Russia has not been this weak — militarily, economically, politically — since the immediate end of the Cold War.

This begs a question. If the U.S. won’t help to deter Russia now, when will it? If the U.S. won’t draw a line against a weakened adversary, what signal does that send to a much stronger one such as China? And what happens when Beijing then moves against Taiwan?

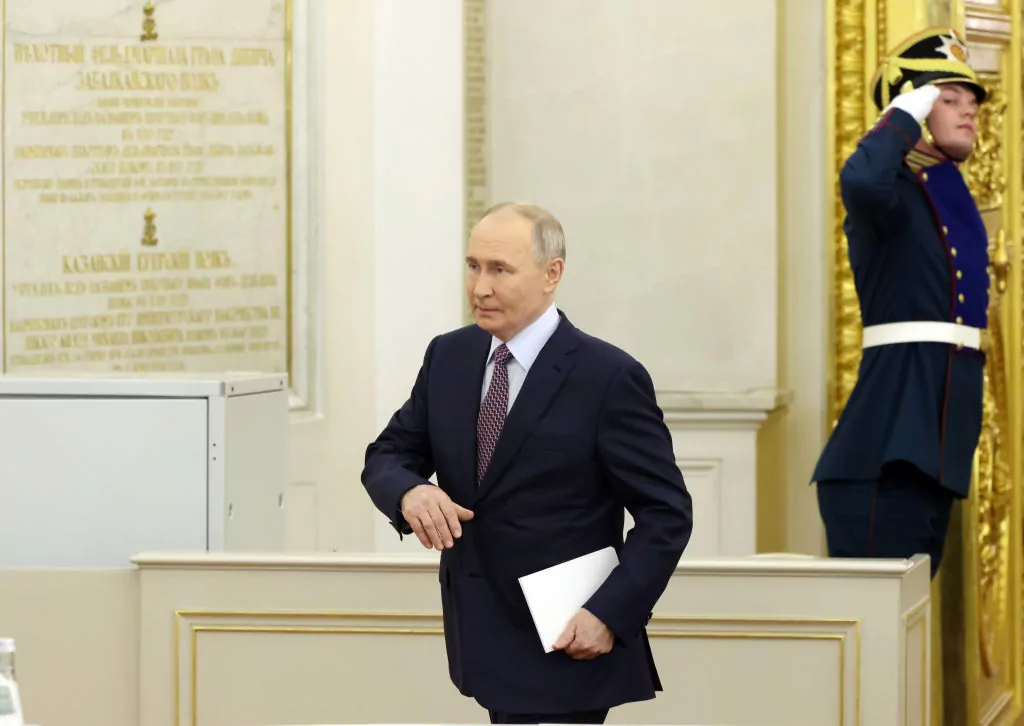

Vladimir Putin’s rise offers a glimpse of the cost of underestimating threats and accommodating adversaries.

When Boris Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned on New Year’s Eve in 1999, he named Putin — a largely unknown former KGB officer to replace him. Russia was in a financial crisis, humiliated on the world stage, and desperate for order after the chaos and vodka-filled optics of Yeltsin’s rule. Putin moved quickly. The 1999 apartment bombings, seen by many as false flag attacks conducted by the Russian FSB, precipitated the second war in Chechnya. That war quickly cemented Putin’s popularity. He then targeted independent media outlets and began consolidating power.

By 2003, Putin turned on the very oligarchs who had empowered him. When Mikhail Khodorkovsky publicly challenged him, he was arrested and his oil empire dismantled. Others — like Berezovsky — ended up dead in exile. A new class of loyalists and oligarchs took their place, while critics like Litvinenko, Politkovskaya, Nemtsov, and Navalny paid with their lives.

Still, Putin continued to sell himself as a modernizer. He managed to deliver improved economic growth. Western leaders cultivated him. But after building strength at home, in 2007, Putin revealed his true intentions at the Munich Security Conference. He denounced America and called the Soviet Union’s collapse the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the century. One year later, Russian troops invaded Georgia. In 2014, Russia struck again. Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula was forcibly annexed and war erupted in that country’s southeast. In 2015, Moscow threw its military behind Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Each time, the West looked away.

Successive U.S. presidents tried to accommodate or appease Putin’s aggression. After Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, Obama gave Moscow a “reset” free pass. When Crimea was annexed and war broke out in Donbas, Obama withheld defensive weapons from Ukraine, fearing escalation. Biden followed a similar path — imposing sanctions and issuing warnings but failing to deter Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. Ironically, it was Trump — often accused of being soft on Russia — who sent lethal aid to Ukraine, sanctioned Nord Stream 2, ordered strikes on Russian Wagner mercenaries in Syria, and bombed Assad’s forces with little more than verbal pushback from Moscow.

Then came the Ukraine war. Putin expected Kyiv to fall in three days but failed. It shattered the illusion of Russian strength. The war that was meant to assert Moscow’s power instead exposed its limits.

That had consequences far beyond the battlefield. In Syria, Moscow couldn’t stop Assad’s fall to rebels. Closer to home, Russia failed its ally Armenia in 2023, standing aside as Azerbaijan retook Nagorno-Karabakh, prompting that country to pivot westward. Moldova, long influenced by Russia, is expelling Russian diplomats and turning decisively toward Europe. Even Cyprus, traditionally friendly to Russian interests, now negotiates Western arms deals and considers hosting a U.S. air base.

Further compounding Russia’s setbacks, Sweden and Finland joined NATO, effectively turning the Baltic Sea into a NATO-controlled lake. Europe, historically compliant with Moscow, is increasing defense spending and showing unity against Russian aggression.

Putin’s failures in Ukraine have exposed the limits of Russian power. But if that power isn’t checked, it will return. From Central Asia and the Caucasus to the Balkans, governments are watching closely to see whether the West holds the line. The Kremlin is betting on Western weakness. So is China. And weakness is provocative.

This bears noting in light of Trump’s continued peace efforts in Ukraine. Because any negotiated outcome must remove the temptation for future Russian adventurism. The only credible deterrents are either NATO guarantees for Ukraine’s future security or the deployment of European troops, backed by American military power, along Ukraine’s frontlines. Anything less points to Western weakness.

WHY TRUMP’S TARIFFS ARE HARMFUL

Accommodating rhetoric — heard across the political spectrum in Washington — is often framed as necessary to avoid World War III. But what actually risks that calamity is the choice to let Russia walk away from this war with a short-term cease-fire. One that gives it time to regroup, rearm, and eventually return. We’ve seen this before: after the 2008 war in Georgia and in 2014 in Ukraine.

Deterrence isn’t just about ending this war — it’s about preventing the next. What message would it send to Beijing if Washington threw Ukraine under the bus in the face of a weakened adversary like Russia?

Ani Chkhikvadze is a writer and former Voice of America reporter based in Washington, DC