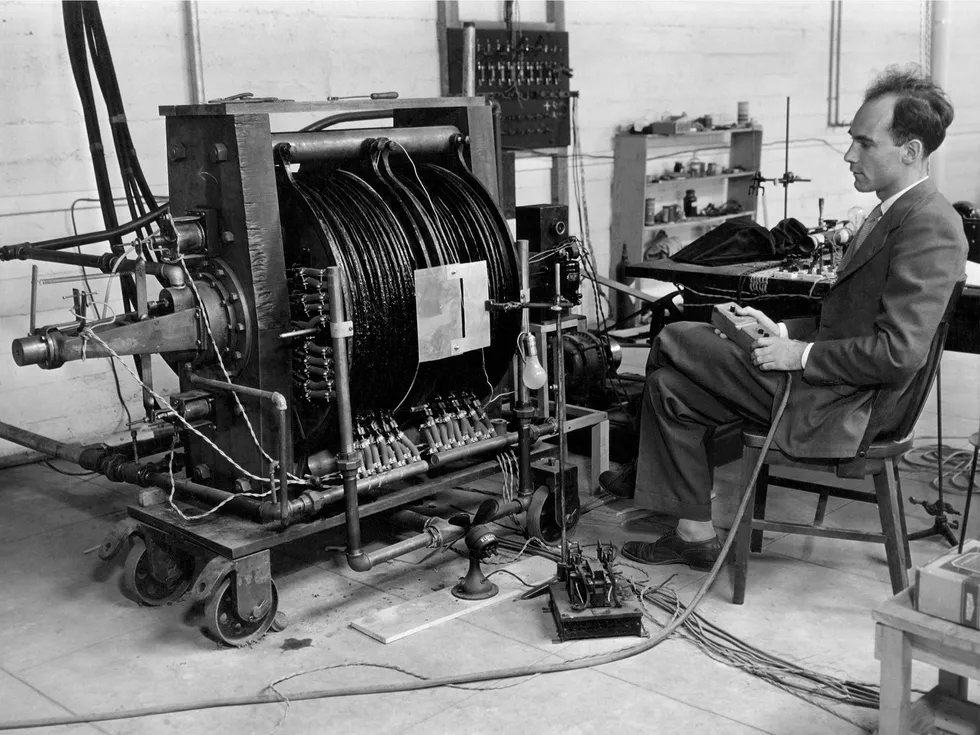

In 1930, a young physicist named Carl D. Anderson was tasked by his mentor with measuring the energies of cosmic rays—particles arriving at high speed from outer space. Anderson built an improved version of a cloud chamber, a device that visually records the trajectories of particles. In 1932, he saw evidence that confusingly combined the properties of protons and electrons. “A situation began to develop that had its awkward aspects,” he wrote many years after winning a Nobel Prize at the age of 31. Anderson had accidentally discovered antimatter.

Four years after his first discovery, he codiscovered another elementary particle, the muon. This one prompted one physicist to ask, “Who ordered that?”

Carl Anderson [top] sits beside the magnet cloud chamber he used to discover the positron. His cloud-chamber photograph [bottom] from 1932 shows the curved track of a positron, the first known antimatter particle. Caltech Archives & Special Collections

Carl Anderson [top] sits beside the magnet cloud chamber he used to discover the positron. His cloud-chamber photograph [bottom] from 1932 shows the curved track of a positron, the first known antimatter particle. Caltech Archives & Special Collections

Over the decades since then, particle physicists have built increasingly sophisticated instruments of exploration. At the apex of these physics-finding machines sits the Large Hadron Collider, which in 2022 started its third operational run. This underground ring, 27 kilometers in circumference and straddling the border between France and Switzerland, was built to slam subatomic particles together at near light speed and test deep theories of the universe. Physicists from around the world turn to the LHC, hoping to find something new. They’re not sure what, but they hope to find it.

It’s the latest manifestation of a rich tradition. Throughout the history of science, new instruments have prompted hunts for the unexpected. Galileo Galilei built telescopes and found Jupiter’s moons. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek built microscopes and noticed “animalcules, very prettily a-moving.” And still today, people peer through lenses and pore through data in search of patterns they hadn’t hypothesized. Nature’s secrets don’t always come with spoilers, and so we gaze into the unknown, ready for anything.

But novel, fundamental aspects of the universe are growing less forthcoming. In a sense, we’ve plucked the lowest-hanging fruit. We know to a good approximation what the building blocks of matter are. The Standard Model of particle physics, which describes the currently known elementary particles, has been in place since the 1970s. Nature can still surprise us, but it typically requires larger or finer instruments, more detailed or expansive data, and faster or more flexible analysis tools.

Those analysis tools include a form of artificial intelligence (AI) called machine learning. Researchers train complex statistical models to find patterns in their data, patterns too subtle for human eyes to see, or too rare for a single human to encounter. At the LHC, which smashes together protons to create immense bursts of energy that decay into other short-lived particles of matter, a theorist might predict some new particle or interaction and describe what its signature would look like in the LHC data, often using a simulation to create synthetic data. Experimentalists would then collect petabytes of measurements and run a machine learning algorithm that compares them with the simulated data, looking for a match. Usually, they come up empty. But maybe new algorithms can peer into corners they haven’t considered.

A New Path for Particle Physics

“You’ve heard probably that there’s a crisis in particle physics,” says Tilman Plehn, a theoretical physicist at Heidelberg University, in Germany. At the LHC and other high-energy physics facilities around the world, the experimental results have failed to yield insights on new physics. “We have a lot of unhappy theorists who thought that their model would have been discovered, and it wasn’t,” Plehn says.

Tilman Plehn

“We have a lot of unhappy theorists who thought that their model would have been discovered, and it wasn’t.”

Gregor Kasieczka, a physicist at the University of Hamburg, in Germany, recalls the field’s enthusiasm when the LHC began running in 2008. Back then, he was a young graduate student and expected to see signs of supersymmetry, a theory predicting heavier versions of the known matter particles. The presumption was that “we turn on the LHC, and supersymmetry will jump in your face, and we’ll discover it in the first year or so,” he tells me. Eighteen years later, supersymmetry remains in the theoretical realm. “I think this level of exuberant optimism has somewhat gone.”

The result, Plehn says, is that models for all kinds of things have fallen in the face of data. “And I think we’re going on a different path now.”

That path involves a kind of machine learning called unsupervised learning. In unsupervised learning, you don’t teach the AI to recognize your specific prediction—signs of a particle with this mass and this charge. Instead, you might teach it to find anything out of the ordinary, anything interesting—which could indicate brand new physics. It’s the equivalent of looking with fresh eyes at a starry sky or a slide of pond scum. The problem is, how do you automate the search for something “interesting”?

Going Beyond the Standard Model

The Standard Model leaves many questions unanswered. Why do matter particles have the masses they do? Why do neutrinos have mass at all? Where is the particle for transmitting gravity, to match those for the other forces? Why do we see more matter than antimatter? Are there extra dimensions? What is dark matter—the invisible stuff that makes up most of the universe’s matter and that we assume to exist because of its gravitational effect on galaxies? Answering any of these questions could open the door to new physics, or fundamental discoveries beyond the Standard Model.

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN accelerates protons to near light speed before smashing them together in hopes of discovering “new physics.”

CERN

“Personally, I’m excited for portal models of dark sectors,” Kasieczka says, as if reading from a Marvel film script. He asks me to imagine a mirror copy of the Standard Model out there somewhere, sharing only one “portal” particle with the Standard Model we know and love. It’s as if this portal particle has a second secret family.

Kasieczka says that in the LHC’s third run, scientists are splitting their efforts roughly evenly between measuring more precisely what they know to exist and looking for what they don’t know to exist. In some cases, the former could enable the latter. The Standard Model predicts certain particle properties and the relationships between them. For example, it correctly predicted a property of the electron called the magnetic moment to about one part in a trillion. And precise measurements could turn up internal inconsistencies. “Then theorists can say, ‘Oh, if I introduce this new particle, it fixes this specific problem that you guys found. And this is how you look for this particle,’” Kasieczka says.

An image from a single collision at the LHC shows an unusually complex spray of particles, flagged as anomalous by machine learning algorithms.

CERN

What’s more, the Standard Model has occasionally shown signs of cracks. Certain particles containing bottom quarks, for example, seem to decay into other particles in unexpected ratios. Plehn finds the bottom-quark incongruities intriguing. “Year after year, I feel they should go away, and they don’t. And nobody has a good explanation,” he says. “I wouldn’t even know who I would shout at”—the theorists or the experimentalists—“like, ‘Sort it out!’”

Exasperation isn’t exactly the right word for Plehn’s feelings, however. Physicists feel gratified when measurements reasonably agree with expectations, he says. “But I think deep down inside, we always hope that it looks unreasonable. Everybody always looks for the anomalous stuff. Everybody wants to see the standard explanation fail. First, it’s fame”—a chance for a Nobel—“but it’s also an intellectual challenge, right? You get excited when things don’t work in science.”

How Unsupervised AI Can Probe for New Physics

Now imagine you had a machine to find all the times things don’t work in science, to uncover all the anomalous stuff. That’s how researchers are using unsupervised learning. One day over ice cream, Plehn and a friend who works at the software company SAP began discussing autoencoders, one type of unsupervised learning algorithm. “He tells me that autoencoders are what they use in industry to see if a network was hacked,” Plehn remembers. “You have, say, a hundred computers, and they have network traffic. If the network traffic [to one computer] changes all of a sudden, the computer has been hacked, and they take it offline.”

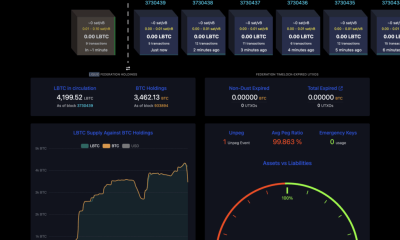

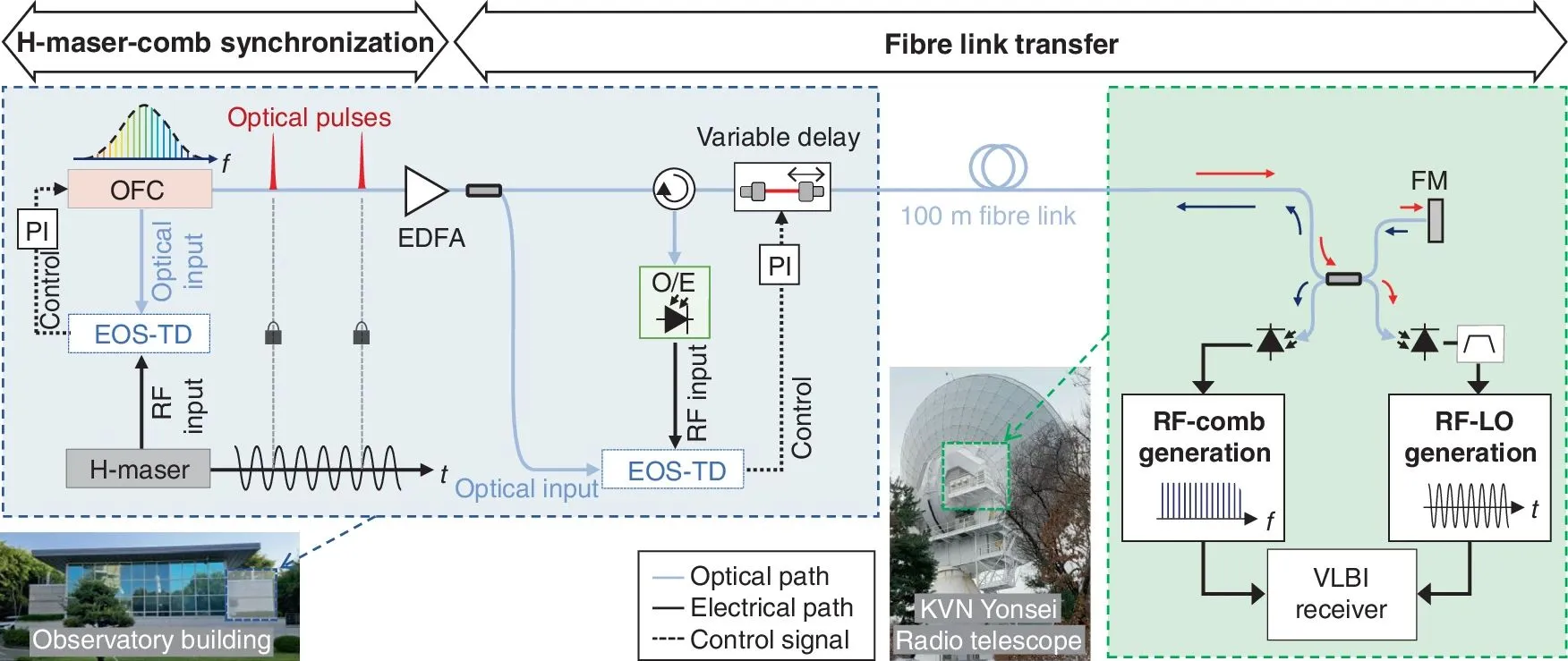

In the LHC’s central data-acquisition room [top], incoming detector data flows through racks of electronics and field-programmable gate array (FPGA) cards [bottom] that decide which collision events to keep.

Fermilab/CERN

Autoencoders are neural networks that start with an input—it could be an image of a cat, or the record of a computer’s network traffic—and compress it, like making a tiny JPEG or MP3 file, and then decompress it. Engineers train them to compress and decompress data so that the output matches the input as closely as possible. Eventually a network becomes very good at that task. But if the data includes some items that are relatively rare—such as white tigers, or hacked computers’ traffic—the network performs worse on these, because it has less practice with them. The difference between an input and its reconstruction therefore signals how anomalous that input is.

“This friend of mine said, ‘You can use exactly our software, right?’” Plehn remembers. “‘It’s exactly the same question. Replace computers with particles.’” The two imagined feeding the autoencoder signatures of particles from a collider and asking: Are any of these particles not like the others? Plehn continues: “And then we wrote up a joint grant proposal.”

It’s not a given that AI will find new physics. Even learning what counts as interesting is a daunting hurdle. Beginning in the 1800s, men in lab coats delegated data processing to women, whom they saw as diligent and detail oriented. Women annotated photos of stars, and they acted as “computers.” In the 1950s, women were trained to scan bubble chambers, which recorded particle trajectories as lines of tiny bubbles in fluid. Physicists didn’t explain to them the theory behind the events, only what to look for based on lists of rules.

But, as the Harvard science historian Peter Galison writes in Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Physics, his influential account of how physicists’ tools shape their discoveries, the task was “subtle, difficult, and anything but routinized,” requiring “three-dimensional visual intuition.” He goes on: “Even within a single experiment, judgment was required—this was not an algorithmic activity, an assembly line procedure in which action could be specified fully by rules.”

Gregor Kasieczka

Gregor Kasieczka

“We are not looking for flying elephants but instead a few extra elephants than usual at the local watering hole.”

Over the last decade, though, one thing we’ve learned is that AI systems can, in fact, perform tasks once thought to require human intuition, such as mastering the ancient board game Go. So researchers have been testing AI’s intuition in physics. In 2019, Kasieczka and his collaborators announced the LHC Olympics 2020, a contest in which participants submitted algorithms to find anomalous events in three sets of (simulated) LHC data. Some teams correctly found the anomalous signal in one dataset, but some falsely reported one in the second set, and they all missed it in the third. In 2020, a research collective called Dark Machines announced a similar competition, which drew more than 1,000 submissions of machine learning models. Decisions about how to score them led to different rankings, showing that there’s no best way to explore the unknown.

Another way to test unsupervised learning is to play revisionist history. In 1995, a particle dubbed the top quark turned up at the Tevatron, a particle accelerator at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), in Illinois. But what if it actually hadn’t? Researchers applied unsupervised learning to LHC data collected in 2012, pretending they knew almost nothing about the top quark. Sure enough, the AI revealed a set of anomalous events that were clustered together. Combined with a bit of human intuition, they pointed toward something like the top quark.

Georgia Karagiorgi

“An algorithm that can recognize any kind of disturbance would be a win.”

That exercise underlines the fact that unsupervised learning can’t replace physicists just yet. “If your anomaly detector detects some kind of feature, how do you get from that statement to something like a physics interpretation?” Kasieczka says. “The anomaly search is more a scouting-like strategy to get you to look into the right corner.” Georgia Karagiorgi, a physicist at Columbia University, agrees. “Once you find something unexpected, you can’t just call it quits and be like, ‘Oh, I discovered something,’” she says. “You have to come up with a model and then test it.”

Kyle Cranmer, a physicist and data scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who played a key role in the discovery of the Higgs boson particle in 2012, also says that human expertise can’t be dismissed. “There’s an infinite number of ways the data can look different from what you expected,” he says, “and most of them aren’t interesting.” Physicists might be able to recognize whether a deviation suggests some plausible new physical phenomenon, rather than just noise. “But how you try to codify that and make it explicit in some algorithm is much less straightforward,” Cranmer says. Ideally, the guidelines would be general enough to exclude the unimaginable without eliminating the merely unimagined. “That’s gonna be your Goldilocks situation.”

In his 1987 book How Experiments End, Harvard’s Galison writes that scientific instruments can “import assumptions built into the apparatus itself.” He tells me about a 1973 experiment that looked for a phenomenon called neutral currents, signaled by an absence of a so-called heavy electron (later renamed the muon). One team initially used a trigger left over from previous experiments, which recorded events only if they produced those heavy electrons—even though neutral currents, by definition, produce none. As a result, for some time the researchers missed the phenomenon and wrongly concluded that it didn’t exist. Galison says that the physicists’ design choice “allowed the discovery of [only] one thing, and it blinded the next generation of people to this new discovery. And that is always a risk when you’re being selective.”

How AI Could Miss—or Fake—New Physics

I ask Galison if by automating the search for interesting events, we’re letting the AI take over the science. He rephrases the question: “Have we handed over the keys to the car of science to the machines?” One way to alleviate such concerns, he tells me, is to generate test data to see if an algorithm behaves as expected—as in the LHC Olympics. “Before you take a camera out and photograph the Loch Ness Monster, you want to make sure that it can reproduce a wide variety of colors” and patterns accurately, he says, so you can rely on it to capture whatever comes.

Galison, who is also a physicist, works on the Event Horizon Telescope, which images black holes. For that project, he remembers putting up utterly unexpected test images like Frosty the Snowman so that scientists could probe the system’s general ability to catch something new. “The danger is that you’ve missed out on some crucial test,” he says, “and that the object you’re going to be photographing is so different from your test patterns that you’re unprepared.”

The algorithms that physicists are using to seek new physics are certainly vulnerable to this danger. It helps that unsupervised learning is already being used in many applications. In industry, it’s surfacing anomalous credit-card transactions and hacked networks. In science, it’s identifying earthquake precursors, genome locations where proteins bind, and merging galaxies.

But one difference with particle-physics data is that the anomalies may not be stand-alone objects or events. You’re looking not just for a needle in a haystack; you’re also looking for subtle irregularities in the haystack itself. Maybe a stack contains a few more short stems than you’d expect. Or a pattern reveals itself only when you simultaneously look at the size, shape, color, and texture of stems. Such a pattern might suggest an unacknowledged substance in the soil. In accelerator data, subtle patterns might suggest a hidden force. As Kasieczka and his colleagues write in one paper, “We are not looking for flying elephants, but instead a few extra elephants than usual at the local watering hole.”

Even algorithms that weigh many factors can miss signals—and they can also see spurious ones. The stakes of mistakenly claiming discovery are high. Going back to the hacking scenario, Plehn says, a company might ultimately determine that its network wasn’t hacked; it was just a new employee. The algorithm’s false positive causes little damage. “Whereas if you stand there and get the Nobel Prize, and a year later people say, ‘Well, it was a fluke,’ people would make fun of you for the rest of your life,” he says. In particle physics, he adds, you run the risk of spotting patterns purely by chance in big data, or as a result of malfunctioning equipment.

False alarms have happened before. In 1976, a group at Fermilab led by Leon Lederman, who later won a Nobel for other work, announced the discovery of a particle they tentatively called the Upsilon. The researchers calculated the probability of the signal’s happening by chance as 1 in 50. After further data collection, though, they walked back the discovery, calling the pseudo-particle the Oops-Leon. (Today, particle physicists wait until the chance that a finding is a fluke drops below 1 in 3.5 million, the so-called five-sigma criterion.) And in 2011, researchers at the Oscillation Project with Emulsion-tRacking Apparatus (OPERA) experiment, in Italy, announced evidence for faster-than-light travel of neutrinos. Then, a few months later, they reported that the result was due to a faulty connection in their timing system.

Those cautionary tales linger in the minds of physicists. And yet, even while researchers are wary of false positives from AI, they also see it as a safeguard against them. So far, unsupervised learning has discovered no new physics, despite its use on data from multiple experiments at Fermilab and CERN. But anomaly detection may have prevented embarrassments like the one at OPERA. “So instead of telling you there’s a new physics particle,” Kasieczka says, “it’s telling you, this sensor is behaving weird today. You should restart it.”

Hardware for AI-Assisted Particle Physics

Particle physicists are pushing the limits of not only their computing software but also their computing hardware. The challenge is unparalleled. The LHC produces 40 million particle collisions per second, each of which can produce a megabyte of data. That’s much too much information to store, even if you could save it to disk that quickly. So the two largest detectors each use two-level data filtering. The first layer, called the Level-1 Trigger, or L1T, harvests 100,000 events per second, and the second layer, called the High-Level Trigger, or HLT, plucks 1,000 of those events to save for later analysis. So only one in 40,000 events is ever potentially seen by human eyes.

Katya Govorkova

“That’s when I thought, we need something like [AlphaGo] in physics. We need a genius that can look at the world differently.”

HLTs use central processing units (CPUs) like the ones in your desktop computer, running complex machine learning algorithms that analyze collisions based on the number, type, energy, momentum, and angles of the new particles produced. L1Ts, as a first line of defense, must be fast. So the L1Ts rely on integrated circuits called field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), which users can reprogram for specialized calculations.

The trade-off is that the programming must be relatively simple. The FPGAs can’t easily store and run fancy neural networks; instead they follow scripted rules about, say, what features of a particle collision make it important. In terms of complexity level, it’s the instructions given to the women who scanned bubble chambers, not the women’s brains.

Ekaterina (Katya) Govorkova, a particle physicist at MIT, saw a path toward improving the LHC’s filters, inspired by a board game. Around 2020, she was looking for new physics by comparing precise measurements at the LHC with predictions, using little or no machine learning. Then she watched a documentary about AlphaGo, the program that used machine learning to beat a human Go champion. “For me the moment of realization was when AlphaGo would use some absolutely new type of strategy that humans, who played this game for centuries, hadn’t thought about before,” she says. “So that’s when I thought, we need something like that in physics. We need a genius that can look at the world differently.” New physics may be something we’d never imagine.

Govorkova and her collaborators found a way to compress autoencoders to put them on FPGAs, where they process an event every 80 nanoseconds (less than 10-millionth of a second). (Compression involved pruning some network connections and reducing the precision of some calculations.) They published their methods in Nature Machine Intelligence in 2022, and researchers are now using them during the LHC’s third run. The new trigger tech is installed in one of the detectors around the LHC’s giant ring, and it has found many anomalous events that would otherwise have gone unflagged.

Researchers are currently setting up analysis workflows to decipher why the events were deemed anomalous. Jennifer Ngadiuba, a particle physicist at Fermilab who is also one of the coordinators of the trigger system (and one of Govorkova’s coauthors), says that one feature stands out already: Flagged events have lots of jets of new particles shooting out of the collisions. But the scientists still need to explore other factors, like the new particles’ energies and their distributions in space. “It’s a high-dimensional problem,” she says.

Eventually they will share the data openly, allowing others to eyeball the results or to apply new unsupervised learning algorithms in the hunt for patterns. Javier Duarte, a physicist at the University of California, San Diego, and also a coauthor on the 2022 paper, says, “It’s kind of exciting to think about providing this to the community of particle physicists and saying, like, ‘Shrug, we don’t know what this is. You can take a look.’” Duarte and Ngadiuba note that high-energy physics has traditionally followed a top-down approach to discovery, testing data against well-defined theories. Adding in this new bottom-up search for the unexpected marks a new paradigm. “And also a return of sorts to before the Standard Model was so well established,” Duarte adds.

Yet it could be years before we know why AI marked those collisions as anomalous. What conclusions could they support? “In the worst case, it could be some detector noise that we didn’t know about,” which would still be useful information, Ngadiuba says. “The best scenario could be a new particle. And then a new particle implies a new force.”

Jennifer Ngadiuba

“The best scenario could be a new particle. And then a new particle implies a new force.”

Duarte says he expects their work with FPGAs to have wider applications. “The data rates and the constraints in high-energy physics are so extreme that people in industry aren’t necessarily working on this,” he says. “In self-driving cars, usually millisecond latencies are sufficient reaction times. But we’re developing algorithms that need to respond in microseconds or less. We’re at this technological frontier, and to see how much that can proliferate back to industry will be cool.”

Plehn is also working to put neural networks on FPGAs for triggers, in collaboration with experimentalists, electrical engineers, and other theorists. Encoding the nuances of abstract theories into material hardware is a puzzle. “In this grant proposal, the person I talked to most is the electrical engineer,” he says, “because I have to ask the engineer, which of my algorithms fits on your bloody FPGA?”

Hardware is hard, says Ryan Kastner, an electrical engineer and computer scientist at UC San Diego who works with Duarte on programming FPGAs. What allows the chips to run algorithms so quickly is their flexibility. Instead of programming them in an abstract coding language like Python, engineers configure the underlying circuitry. They map logic gates, route data paths, and synchronize operations by hand. That low-level control also makes the effort “painfully difficult,” Kastner says. “It’s kind of like you have a lot of rope, and it’s very easy to hang yourself.”

Seeking New Physics Among the Neutrinos

The next piece of new physics may not pop up at a particle accelerator. It may appear at a detector for neutrinos, particles that are part of the Standard Model but remain deeply mysterious. Neutrinos are tiny, electrically neutral, and so light that no one has yet measured their mass. (The latest attempt, in April, set an upper limit of about a millionth the mass of an electron.) Of all known particles with mass, neutrinos are the universe’s most abundant, but also among the most ghostly, rarely deigning to acknowledge the matter around them. Tens of trillions pass through your body every second.

If we listen very closely, though, we may just hear the secrets they have to tell. Karagiorgi, of Columbia, has chosen this path to discovery. Being a physicist is “kind of like playing detective, but where you create your own mysteries,” she tells me during my visit to Columbia’s Nevis Laboratories, located on a large estate about 20 km north of Manhattan. Physics research began at the site after World War II; one hallway features papers going back to 1951.

A researcher stands inside a prototype for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, which is designed to detect rare neutrino interactions.

CERN

Karagiorgi is eagerly awaiting a massive neutrino detector that’s currently under construction. Starting in 2028, Fermilab will send neutrinos west through 1,300 km of rock to South Dakota, where they’ll occasionally make their existence known in the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE). Why so far away? When neutrinos travel long distances, they have an odd habit of oscillating, transforming from one kind or “flavor” to another. Observing the oscillations of both the neutrinos and their mirror-image antiparticles, antineutrinos, could tell researchers something about the universe’s matter-antimatter asymmetry—which the Standard Model doesn’t explain—and thus, according to the Nevis website, “why we exist.”

“DUNE is the thing that’s been pushing me to develop these real-time AI methods,” Karagiorgi says, “for sifting through the data very, very, very quickly and trying to look for rare signatures of interest within them.” When neutrinos interact with the detector’s 70,000 tonnes of liquid argon, they’ll generate a shower of other particles, creating visual tracks that look like a photo of fireworks.

The Standard Model catalogs the known fundamental particles of matter and the forces that govern them, but leaves major mysteries unresolved.

Even when not bombarding DUNE with neutrinos, researchers will keep collecting data in the off chance that it captures neutrinos from a distant supernova. “This is a massive detector spewing out 5 terabytes of data per second,” Karagiorgi says, “and it’s going to run constantly for a decade.” They will need unsupervised learning to notice signatures that no one was looking for, because there are “lots of different models of how supernova explosions happen, and for all we know, none of them could be the right model for neutrinos,” she says. “To train your algorithm on such uncertain grounds is less than ideal. So an algorithm that can recognize any kind of disturbance would be a win.”

Deciding in real time which 1 percent of 1 percent of data to keep will require FPGAs. Karagiorgi’s team is preparing to use them for DUNE, and she walks me to a computer lab where they program the circuits. In the FPGA lab, we look at nondescript circuit boards sitting on a table. “So what we’re proposing is a scheme where you can have something like a hundred of these boards for DUNE deep underground that receive the image data frame by frame,” she says. This system could tell researchers whether a given frame resembled TV static, fireworks, or something in between.

Neutrino experiments, like many particle-physics studies, are very visual. When Karagiorgi was a postdoc, automated image processing at neutrino detectors was still in its infancy, so she and collaborators would often resort to visual scanning (bubble-chamber style) to measure particle tracks. She still asks undergrads to hand-scan as an educational exercise. “I think it’s wrong to just send them to write a machine learning algorithm. Unless you can actually visualize the data, you don’t really gain a sense of what you’re looking for,” she says. “I think it also helps with creativity to be able to visualize the different types of interactions that are happening, and see what’s normal and what’s not normal.”

Back in Karagiorgi’s office, a bulletin board displays images from The Cognitive Art of Feynman Diagrams, an exhibit for which the designer Edward Tufte created wire sculptures of the physicist Richard Feynman’s schematics of particle interactions. “It’s funny, you know,” she says. “They look like they’re just scribbles, right? But actually, they encode quantitatively predictive behavior in nature.” Later, Karagiorgi and I spend a good 10 minutes discussing whether a computer or a human could find Waldo without knowing what Waldo looked like. We also touch on the 1964 Supreme Court case in which Justice Potter Stewart famously declined to define obscenity, saying “I know it when I see it.” I ask whether it seems weird to hand over to a machine the task of deciding what’s visually interesting. “There are a lot of trust issues,” she says with a laugh.

On the drive back to Manhattan, we discuss the history of scientific discovery. “I think it’s part of human nature to try to make sense of an orderly world around you,” Karagiorgi says. “And then you just automatically pick out the oddities. Some people obsess about the oddities more than others, and then try to understand them.”

Reflecting on the Standard Model, she called it “beautiful and elegant,” with “amazing predictive power.” Yet she finds it both limited and limiting, blinding us to colors we don’t yet see. “Sometimes it’s both a blessing and a curse that we’ve managed to develop such a successful theory.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Carl Anderson [top] sits beside the magnet cloud chamber he used to discover the positron. His cloud-chamber photograph [bottom] from 1932 shows the curved track of a positron, the first known antimatter particle.

Carl Anderson [top] sits beside the magnet cloud chamber he used to discover the positron. His cloud-chamber photograph [bottom] from 1932 shows the curved track of a positron, the first known antimatter particle.

Gregor Kasieczka

Gregor Kasieczka

The film “I’ll Take Sweden” featured a Project G, shown here with co-star Tuesday Weld.Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

The film “I’ll Take Sweden” featured a Project G, shown here with co-star Tuesday Weld.Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

Diane Landry, winner of the 1963 Miss Canada beauty pageant, poses with a Project G2. Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

Diane Landry, winner of the 1963 Miss Canada beauty pageant, poses with a Project G2. Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

Clairtone cofounders Peter Munk [left] and David Gilmour envisioned the company as a luxury brand.Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

Clairtone cofounders Peter Munk [left] and David Gilmour envisioned the company as a luxury brand.Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

Peter Munk visits the Project G assembly line in 1965. Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

Peter Munk visits the Project G assembly line in 1965. Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

David Gilmour’s wife, Anna Gilmour, was the company’s first in-house model.Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate

David Gilmour’s wife, Anna Gilmour, was the company’s first in-house model.Nina Munk/The Peter Munk Estate