In 2026, artificial intelligence is everywhere -it writes code, creates images, generates audio and video, analyzes contracts and runs customer support desks. Tech giants compete over model sizes and training data the way carmakers once boasted about horsepower.

And yet, in 1985 – at the dawn of the PC era – some of the industry’s sharpest observers were already warning that AI might be “the most despised and abused [software concept] of the next year.”

Awaiting AI Hype

That line came from Mitch Kapor, chairman of Lotus Development, speaking at the January 1985 Personal Computer Forum.

“The next big lemming-like rush will be to artificial intelligence,” he said. “So in a perverse way, AI is an exciting opportunity for people who recognize what it can do for customers.”

The February 25, 1985 editorial in InfoWorld, titled “Awaiting AI Hype, Promise,” now reads like a dispatch from the future.

“Will 1985 be the year when artificial intelligence finally emerges from the ivory towers of academia to become a useful tool?” James E. Fawcette, the magazine’s Editorial Director & Associate Publisher pondered. “Software companies desperate for new hooks to lure jaded users tired of the parade of me-too spreadsheets and word processors see artificial intelligence, or AI, as a possible savior.”

Sound familiar?

The editorial’s core anxiety could have been written about 2023’s generative AI boom: “The problem is: What can AI really do? Even the words artificial intelligence are a barrier to the technology’s application. They are so value- and image-laden that the term itself obstructs practical work.” AI, Fawcette warned, conjured “thinking machines, complete with Big Brother images of computers controlling our lives or making decisions for us.”

Fawcette also identified two varieties of AI abuse. The first: “AI-hype,” defined as “vacuous programs that promise to make decisions for the user. Simply type in a handful of facts, and the program will run your business for you, tell you what stocks to buy, let you manipulate people.” The second: the “Rube Goldberg overdesign syndrome”—overengineered systems built to solve grand problems rather than practical ones.

If you’ve scrolled through LinkedIn lately, you’ve seen both.

“Given the damage these two schools of thought will cause, it is not surprising that some personal computing evangelists are avoiding AI terminology entirely,” Fawcette continued. “Microsoft’s Bill Gates has coined the term softer software to describe his vision of programs that will learn the user’s work patterns and help execute them.”

Two years earlier, in an August 29, 1983 InfoWorld piece, Bill Gates and Charles Simonyi discussed this very idea. “AI is a very complex goal,” Simonyi said. “You need a philosopher to determine what AI is.”

Instead of artificial intelligence, they proposed “softer software”as a more realistic goal.

This, Simonyi explained, was empirical. “It modifies its behavior over time, based on its experience with the user” with the aim to make life easier for users in the “real world.”

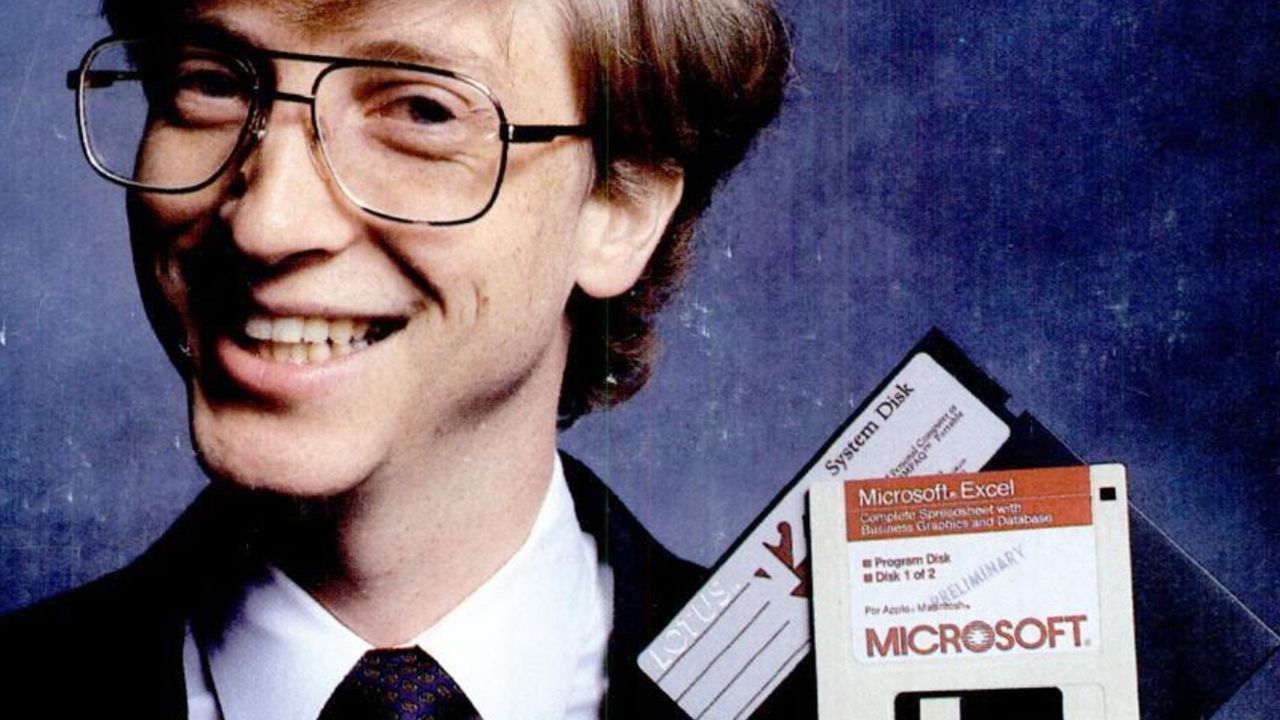

Simonyi is the legendary software architect who led the teams that created Microsoft Word and Excel. If you’ve ever used a “pull-down menu,” clicked an “icon,” or used a “WYSIWYG” (What You See Is What You Get) editor, you are using his legacy.

His description of “softer software” sounds eerily like today’s personalization engines and adaptive copilots. But in 1983, it was radical.

“With softer software,” InfoWorld wrote, “the program might ‘remember’ that whenever you request double-spacing, you also want right-margin justification and a particular heading on each page. The program has learned this by observing your habits. ”

Simonyi predicted in the future that the computer “will be a working partner in the sense of anticipating your behavior and suggesting things to you. It will mold itself based on events that have taken place over a period of time.”

We can definitely recognize that in today’s software and AI assistants.

Excel

“While such descriptions sound futuristic,” InfoWorld wrote, “Microsoft has taken the first tentative steps toward what Gates and Simonyi believe will be the application of the softer-software dream. They call the packages ‘expert systems.’ The first group of expert systems is designed to improve the functionality of Microsoft’s spreadsheet program, Multiplan.”

Multiplan would later be succeeded by Excel, Microsoft’s next-generation spreadsheet software.

“Rather than confronting users with a blank array of empty cells in a spreadsheet, the expert systems can build formulas, create categories and analyze data,” InfoWorld continued. “Gates says that softer software will become commonplace within five years. Simonyi says it is one of a handful of ideas that he likes programmers to keep in mind when they develop the design for a program.”

Two years later, in the May 27, 1985 issue, InfoWorld reviewed the first version of Excel for the Macintosh (Windows 1.0 wouldn’t arrive until later that year). Reviewer Amanda Hixson wrote that Excel’s “learn-by-example macro feature… is the first step toward software that satisfies the promise of ‘softer software,’ as Bill Gates described his dream of a coming generation of products geared to make computer use as easy as possible and still provide maximum performance.”

Excel macros were an early form of user-trained automation. As Hixson wrote, users could “type them in…or use Excel’s learn-by-example method,” where “Excel will remember what you do on a worksheet, write macro code as you do it, then let you rerun what you’ve done by calling the macro.” You didn’t need to understand programming “to create powerful Excel macros.”

Lotus 1-2-3 dominated spreadsheets at the time, but Gates criticized the philosophy behind Lotus Jazz, the company’s new all-in-one software suite. “We don’t believe in the Jazz philosophy… which is to take all your uses — words, numbers, database … and spread them in five different directions. So there is significant compromise.” Microsoft’s approach, he said, was “to take these three areas and do appropriate integration within each area.”

Excel ultimately outlasted Jazz, not by promising magic but by delivering, as Hixson wrote, “consistency, power, lots of features, and macros.”

A copilot not an oracle

In 1985, InfoWorld’s editorial imagined software that could “generate the sales report but this time throw in a bar chart of the European market.”

What once sounded speculative now feels routine to us where AI systems draft quarterly reports, summarize meetings in real time and generate charts from a single sentence. They operate as “agents,” executing multi-step tasks across apps.

The same editorial also included a line that still resonates today: “We’ll get our first taste [of AI] this year. Let’s hope some applications are as intelligent as the software algorithms used to implement them.”

Bill Gates didn’t reject intelligence in software back then, rather he rejected the mythology around it. By talking about “softer software,” he envisioned systems that learned from users, adapted to context and acted as partners, a kind of copilot rather than an all-knowing oracle.

Follow TechRadar on Google News and add us as a preferred source to get our expert news, reviews, and opinion in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button!

And of course you can also follow TechRadar on TikTok for news, reviews, unboxings in video form, and get regular updates from us on WhatsApp too.

![Heathrow has said passenger numbers were 60% lower in November than before the coronavirus pandemic and there were “high cancellations” among business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas for Christmas as Omicron spreads. The UK’s largest airport said the government’s travel restrictions had dealt a fresh blow to travel confidence and predicted it was likely to take several years for passenger numbers to return to pre-pandemic levels. This week ministers said passengers arriving in the UK would have to take a pre-departure Covid test, as well as a post-flight test, because of fears about the spread of the new variant. “[The] high level of cancellations by business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas because of pre-departure testing shows the potential harm to the economy of travel restrictions,” the airport said in an update. Heathrow said the drop in traveller confidence owing to the new travel restrictions had negated the benefit of reopening the all-important corridor to North America for business and holiday travel last month. Eleven African countries have been added to the government’s red list, requiring travellers to quarantine before reuniting with families. “By allowing Brits to isolate at home, ministers can make sure they are reunited with their loved ones this Christmas,” said John Holland-Kaye, the chief executive of Heathrow. “It would send a strong signal that restrictions on travel will be removed as soon as safely possible to give passengers the confidence to book for 2022, opening up thousands of new jobs for local people at Heathrow. Let’s reunite families for Christmas.” Heathrow said that if the government could safely signal that restrictions would be lifted soon, then employers at Heathrow would have the confidence to hire thousands of staff in anticipation of a boost in business next summer. The airport is expecting a slow start to 2022, finishing next year with about 45 million passengers – just over half of pre-pandemic levels. This week Tui, Europe’s largest package holiday operator, said it expected bookings for next summer to bounce back to 2019 levels. However, Heathrow said on Friday not to expect the aviation industry to recover for several years. “We do not expect that international travel will recover to 2019 levels until at least all travel restrictions (including testing) are removed from all the markets that we serve, at both ends of the route, and there is no risk of new restrictions, such as quarantine, being imposed,” the airport said.](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/shutterstock_1100012546-scaled-400x240.jpg)

![Heathrow has said passenger numbers were 60% lower in November than before the coronavirus pandemic and there were “high cancellations” among business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas for Christmas as Omicron spreads. The UK’s largest airport said the government’s travel restrictions had dealt a fresh blow to travel confidence and predicted it was likely to take several years for passenger numbers to return to pre-pandemic levels. This week ministers said passengers arriving in the UK would have to take a pre-departure Covid test, as well as a post-flight test, because of fears about the spread of the new variant. “[The] high level of cancellations by business travellers concerned about being trapped overseas because of pre-departure testing shows the potential harm to the economy of travel restrictions,” the airport said in an update. Heathrow said the drop in traveller confidence owing to the new travel restrictions had negated the benefit of reopening the all-important corridor to North America for business and holiday travel last month. Eleven African countries have been added to the government’s red list, requiring travellers to quarantine before reuniting with families. “By allowing Brits to isolate at home, ministers can make sure they are reunited with their loved ones this Christmas,” said John Holland-Kaye, the chief executive of Heathrow. “It would send a strong signal that restrictions on travel will be removed as soon as safely possible to give passengers the confidence to book for 2022, opening up thousands of new jobs for local people at Heathrow. Let’s reunite families for Christmas.” Heathrow said that if the government could safely signal that restrictions would be lifted soon, then employers at Heathrow would have the confidence to hire thousands of staff in anticipation of a boost in business next summer. The airport is expecting a slow start to 2022, finishing next year with about 45 million passengers – just over half of pre-pandemic levels. This week Tui, Europe’s largest package holiday operator, said it expected bookings for next summer to bounce back to 2019 levels. However, Heathrow said on Friday not to expect the aviation industry to recover for several years. “We do not expect that international travel will recover to 2019 levels until at least all travel restrictions (including testing) are removed from all the markets that we serve, at both ends of the route, and there is no risk of new restrictions, such as quarantine, being imposed,” the airport said.](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/shutterstock_1100012546-scaled-80x80.jpg)