As soon as you drive over the top of the Peak District and down into Sheffield you can see the light pollution – and it’s horrible, said a participant in a research project into darkness and light pollution.

In the last 100 years, the places where people can experience darkness have reduced dramatically. Now only 10% of the people living in the western hemisphere experience places with dark skies, where there is no artificial light. And the starry skies they can see are limited by artificial light. The number of stars that people can see from most of the western hemisphere is getting fewer and fewer.

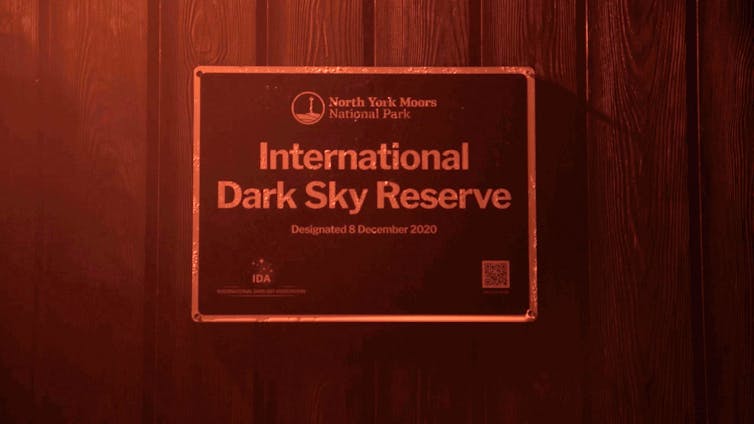

Researchers trying to find out about public attitudes to darkness attended events over three days in the North York Moors National Park. Here, in one of the UK’s seven dark sky reserves (where light pollution is limited), the researchers explored how immersive and fun experiences, such as guided night walks and stargazing and silent discos, reshaped public perceptions of natural darkness and sparked ideas of what they might change in their lives.

Working with a professional film-maker, the research team recorded how people responded to taking part in events in darkness. Participants in the research included five tourism businesses, two representatives from the park and 94 visitors.

Andy Burns.

Darkness disappears

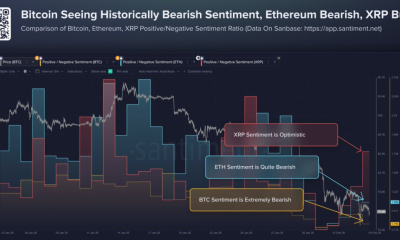

Light pollution is increasing globally by approximately 10% per year (estimated by measuring how many stars can be seen in the sky at night), diminishing night skies and disrupting ecosystems.

But increasing awareness of light pollution has led to an increase in national parks hosting events to explore this issue, according to my recent study.

Andy Burns., CC BY-SA

The study’s findings indicated that participants in the North York Moors Dark Sky Festival events not only started to feel more comfortable in natural darkness but also talked about changing their own lifestyle, including using low-impact lighting in their homes, asking neighbours to switch off lights in their gardens at night, and monitoring neighbourhood light levels.

The research team used filming and walking with visitors to capture not just what people said, but what they did in darkness. During guided walks, participants experimented with moving without head‑torches, cultivating night vision, and tuning into sound, smell and learning how to find their way around without artificial light.

Walking in silence helped visitors build a deeper connection with the nocturnal environment. One visitor said that being in the dark just for that moment of peace, and just to listen and tune in to the environment was a privilege and something to conserve.

One said: “I remember as a child I’d see similar stuff from a city [and that] sort of thing, and now we’re doing whatever we can do to save things like this.”

Visitors reported leaving with new skills, greater awareness and commitment, such as putting their lights at home on timers, and working on bat protection projects. These actions demonstrate that this kind of experience in nocturnal environments can change behaviour far beyond festivals.

Dark Sky activists, such as those in the North York Moors National Park, have learned that the public connect with the issues around light pollution and become more engaged if the activities are fun.

Shared experiences help people understand complex messages about climate, biodiversity, and responsible lighting, and help people feel more confident about walking in the dark. Several participants commented that walking without light was good and wasn’t as bad as they thought. Another said: “I find walking at night with a full moon is really quite a magical experience.”

By the end of the walk, some visitors (when on relatively easy ground) were happy to switch head torches off and enjoy feeling immersed within the nocturnal landscape.

Dark‑sky festivals show how joy and fun can build public awareness and an understanding of why darkness matters.

However, limited public transport to rural night events as well as safety concerns about walking in darkness, and the cost of festivals all restrict participation.

Why light is a problem

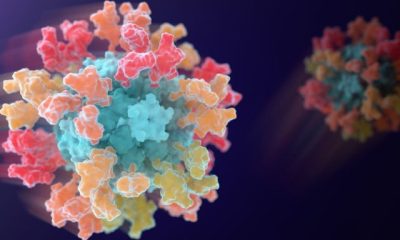

Research shows that artificial light at night disrupts circadian rhythms, impairs some species ability to find their way around and is a cause of declining populations of insects, bats and other nocturnal fauna.

There is also evidence that outdoor lighting generates needless emissions and ecological harm that is intensifying at an alarming rate.

To rethink this shift, the study argues that darkness could be considered a shared environmental “good”, requiring collective care to prevent overuse, damage and pollution.

Small changes in lighting shielding (which controls the spread of light), warmer coloured lights, and half lighting (switching street lighting off at midnight) can be significant and less damaging to animal life.

The national park’s next major step has been to establish a Northern England Dark-Sky Alliance to halt the growth of light pollution outside the park boundaries, particularly along the A1 road in northern England, which would help restore natural darkness for nocturnal migratory species, such as birds like Nightjars.

If we can make living with more darkness in our streets, and in our leisure time, feel more normal and more comfortable, then nighttime becomes not something that needs to be fixed, but a shared commons to be restored.

Jenny Hall is a speaker at an upcoming discussion on Cities Under Stars: Tackling Light Pollution in Cities, in conjunction with The Conversation, as part of this year’s Dark Skies Festival. Find out more, and come along.