Imagine a line of affordable toys controlled by the player’s brainwaves. By interpreting biosignals picked up by the dry electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes in an included headset, the game could infer the wearer’s level of concentration, through which it would be possible to move physical objects or interact with virtual characters. You might naturally assume such devices would be on the cutting-edge of modern technology, perhaps even a spin-off from one of the startups currently investigating brain-computer interfaces (BCIs).

Yet despite considerable interest leading up to their release — fueled at least in part by the fact that one of the models featured Star Wars branding and gave players the illusion of Force powers — the devices failed to make any lasting impact, and have today largely fallen into obscurity. The last toy based on Neurosky’s technology was released in 2015, and disappeared from the market only a few years later.

I had all but forgotten about them myself, until I recently came across a complete Mattel Mindflex at a thrift store for $8.99. It seemed a perfect opportunity to not only examine the nearly 20 year old toy, but to take a look at the origins of the product, and find out what ultimately became of Neurosky’s EEG technology. Was the concept simply ahead of its time? In an era when most people still had flip phones, perhaps consumers simply weren’t ready for this type of BCI. Or was the real problem that the technology simply didn’t work as advertised?

Shall We Play a Game?

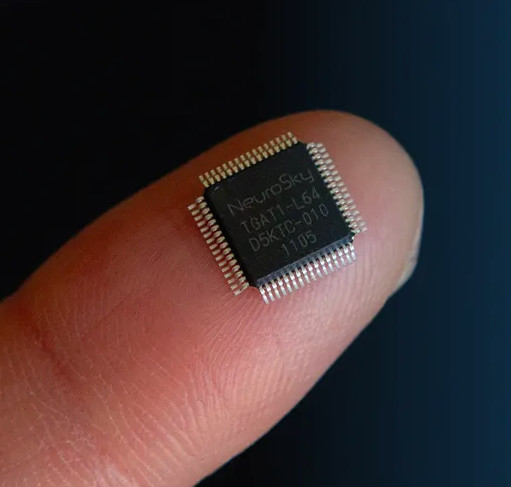

NeuroSky was founded in 1999 to explore commercial applications for BCIs, and as such, they identified two key areas where they thought they could improve upon hardware that was already on the market: cost, and ease of use.

Cost is an easy enough metric to understand and optimize for in this context — if you’re trying to incorporate your technology into games and consumer gadgets, cheaper is better. To reduce costs, their hardware wasn’t as sensitive or as capable as what was available in the medical and research fields, but that wasn’t necessarily a problem for the sort of applications they had in mind.

Of course, it doesn’t matter how cheap you make the hardware if manufacturers can’t figure out how to integrate it into their products, or users can’t make any sense of the information. The average person certainly wouldn’t be able to make heads or tails of the raw data coming from electroencephalography or electromyography sensors, and the engineers looking to graft BCI features into their consumer products weren’t likely to do much better.

To address this, NeuroSky’s technology presented the user with simple 0 to 100 values for more easily conceptualized parameters like concentration and anxiety based on their alpha and beta brainwaves. This made integration into consumer devices far simpler, albeit at the expense of accuracy and flexibility. The user could easily see when values were going up and down, but whether or not those values actually corresponded with a given mental state was entirely up to the interpretation being done inside the hardware.

These values were easy to work with, and with some practice, NeuroSky claimed the user could manipulate them by simply focusing their thoughts. So in theory, a home automation system could watch one of these mental parameters and switch on the lights when the value hit a certain threshold. But the NeuroSky BCI could never actually sense what the user was thinking — at best, it could potentially determine how hard an individual was concentrating on a specific thought. Although in the end, even that was debatable.

The Force Awakens

After a few attempted partnerships that never went anywhere, NeuroSky finally got Mattel interested in 2009. The result was the Mindflex, which tasked the player with maneuvering a floating ball though different openings. The height of the ball, controlled by the speed of the blower motor in the base of the unit, was controlled by the output of the NeuroSky headset. Trying to get two actionable data points out of the hardware was asking a bit much, so moving the ball left and right must be done by hand with a knob.

But while the Mindflex was first, the better known application for NeuroSky’s hardware in the entertainment space is certainly the Star Wars Jedi Force Trainer released by Uncle Milton a few months later. Fundimentally, the game worked the same way as the Mindflex, with the user again tasked with controlling the speed of a blower motor that would raise and lower a ball.

But this time, the obstacles were gone, as was the need for a physical control. It was a simpler game in all respects. Even the ball was constrained in a clear plastic tube, rather than being held in place by the Coandă effect as in the Mindflex. In theory, this made for a less distracting experience, allowing the user to more fully focus on trying to control the height of the ball with their mental state.

But the real hook, of course, was Star Wars. Uncle Milton cleverly wrapped the whole experience around the lore from the films, putting the player in the role of a young Jedi Padawan that’s using the Force Trainer to develop their telekinetic abilities. As the player attempted to accurately control the movement of the ball, voice clips of Yoda would play to encourage them to concentrate harder and focus their minds on the task at hand. Even the ball itself was modeled after the floating “Training Remote” that Luke uses to practice his lightsaber skills in the original film.

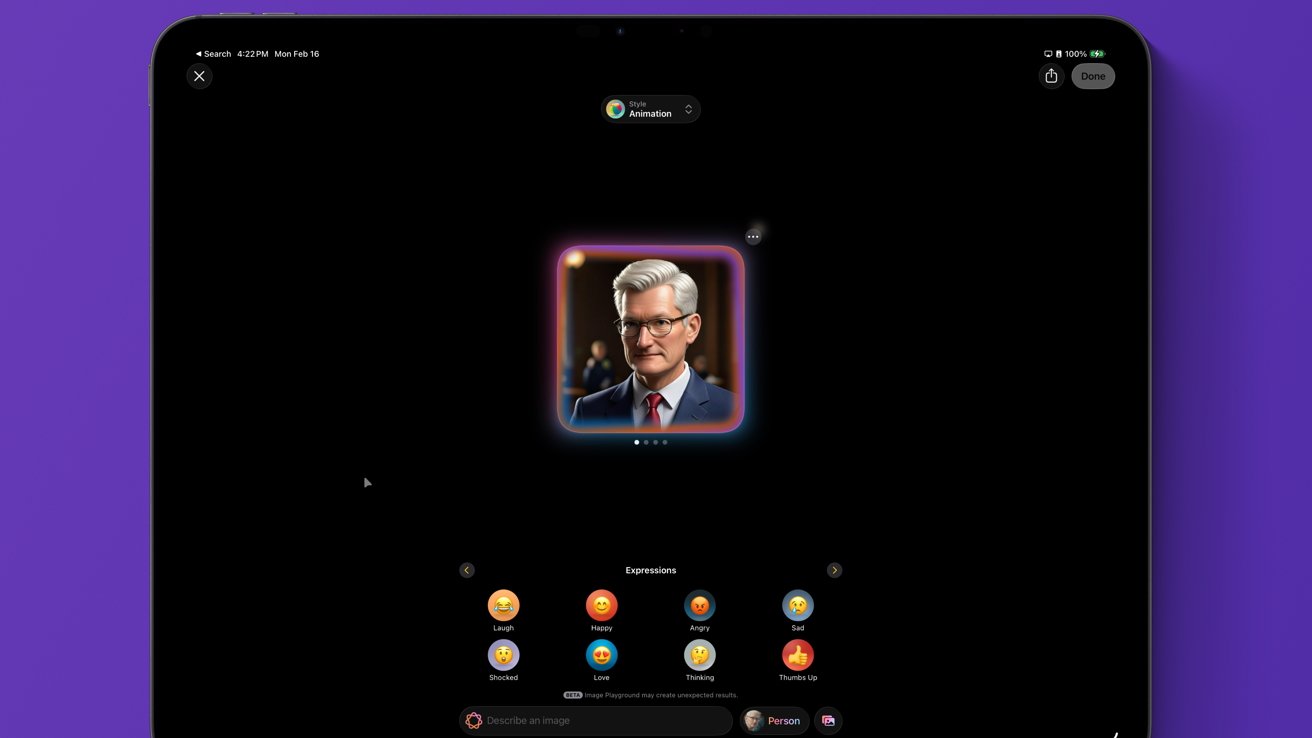

The Force Trainer enjoyed enough commercial success that Uncle Milton produced the Force Trainer II in 2015. This version used a newer NeuroSky headset which featured Bluetooth capability, and paired it with an application running on a user-supplied Android or Apple tablet. The tablet was inserted into a base unit which was able to display “holograms” using the classic Pepper’s Ghost illusion. Rather than simply moving a ball up and down, the young Jedi in training would have to focus their thoughts to virtually lift a 3D model of an X-Wing out of the muck or knock over groups of battle droids.

Unfortunately, Force Trainer II didn’t end up being as successful as its predecessor, and was discontinued a few years later. Even though the core technology was the same as in 2009, the reviews I can still find online for this version of the game are scathing. It seems like most of the technical problems came from the fact that users had to connect the headset to their own device, which introduced all manner of compatibility issues. Others claimed that the game doesn’t actually read the player’s mental state at all, and that the challenges can be beaten even if you don’t wear the headset.

Headset Hacking

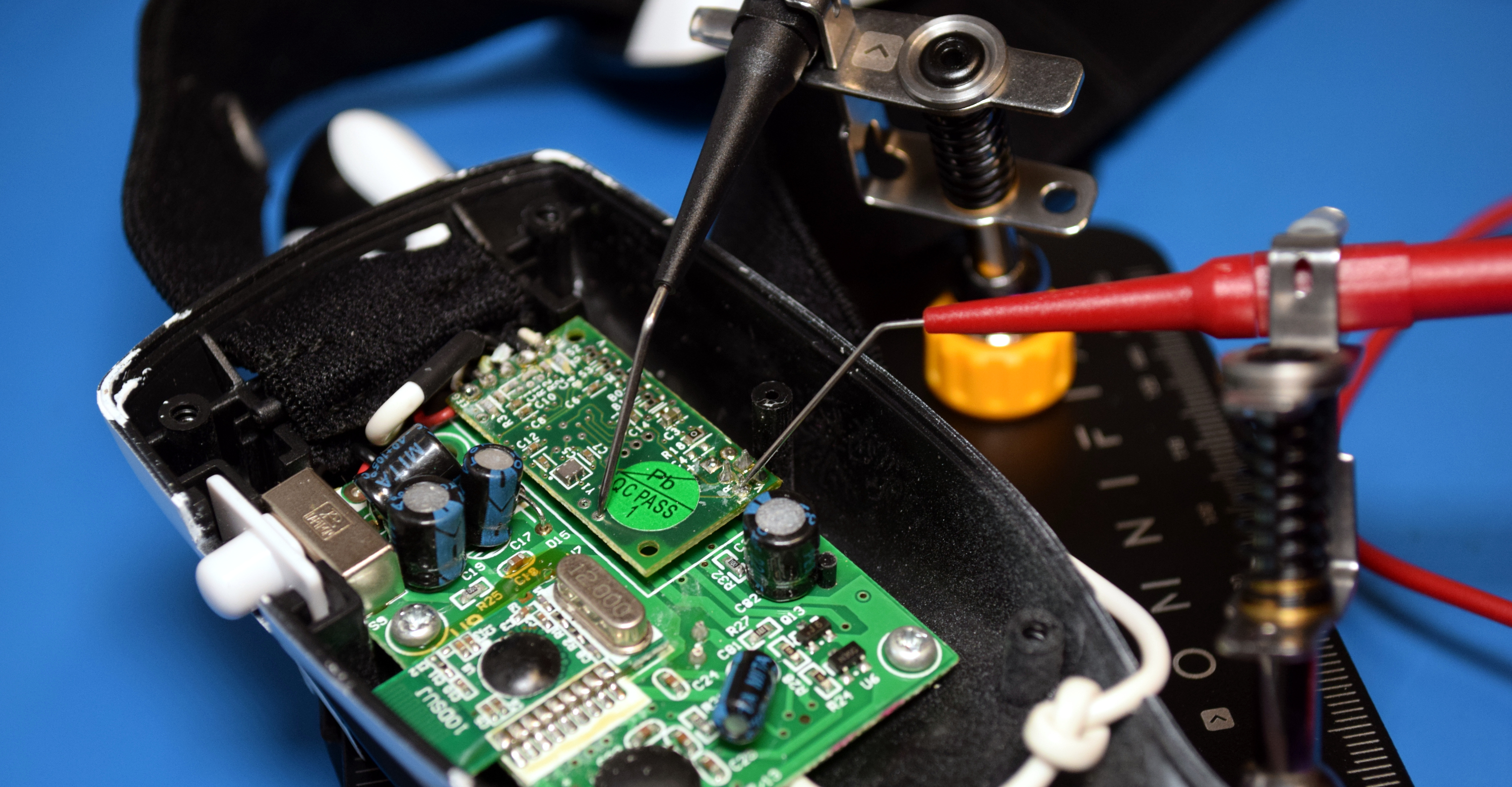

The headsets for both the Mindflex and the original Force Trainer use the same core hardware, and NeuroSky even released their own “developer version” of the headset not long after the games hit the market which could connect to the computer and offered a free SDK.

Over the years, there have been hacks to use the cheaper Mindflex and Force Trainer headsets in place of NeuroSky’s developer version, some of which have graced these very pages. But somehow we missed what seems to be the best source of information: How to Hack Toy EEGs. This page not only features a teardown of the Mindflex headset, but shows how it can be interfaced with the Arduino so brainwave data can be read and processed on the computer.

I haven’t gone too far down this particular rabbit hole, but I did connect the headset up to my trusty Bus Pirate 5 and could indeed see it spewing out serial data. Paired with a modern wireless microcontroller, the Mindflex could still be an interesting device for BCI experimentation all these years later. Though if you can pick up the Bluetooth Force Trainer II headset for cheap on eBay, it sounds like it would save you the trouble of having to hack it yourself.

My Mind to Your Mind

So the big question: does the Mindflex, and by extension NeuroSky’s 2009-era BCI technology, actually work?

Before writing this article, I spent the better part of an hour wearing the Mindflex headset and trying to control the LEDs on the front of the device that are supposed to indicate your focus level. I can confidently say that it’s doing something, but it’s hard to say what. I found that getting the focus indicator to drop down to zero was relatively easy (story of my life) and nearly 100% repeatable, but getting it to go in the other direction was not as consistent. Sometimes I could make the top LEDs blink on and off several times in a row, but then seconds later I would lose it and struggle to light up even half of them.

Some critics have said that the NeuroSky is really just detecting muscle movement in the face — picking up not the wearer’s focus level so much as a twitch of the eye or a furrowed brow which makes it seem like the device is responding to mental effort. For what it’s worth, the manual specifically says to try and keep your face as still as possible, and I couldn’t seem to influence the focus indicator by blinking or making different facial expressions. Although if it actually was just detecting the movement of facial muscles, that would still be a neat trick that offered plenty of potential applications.

I also think that a lot of the bad experiences people have reported with the technology is probably rooted in their own unrealistic expectations. If you tell a child that a toy can read their mind and that they can move an object just by thinking about it, they’re going to take that literally. So when they put on the headset and the game doesn’t respond to their mental image of the ball moving or the LEDs lighting up, it’s only natural they would get frustrated.

So what about the claims that the Force Trainer II could be played without even wearing the headset? If I had to guess, I would say that if there’s any fakery going on, it’s in the game itself and not the actual NeuroSky hardware. Perhaps somebody was worried the experience would be too frustrating for kids, and goosed the numbers so the game could be beaten no matter what.

As for NeuroSky, they’re still making BCI headsets and offer a free SDK for them. You can buy their MindWave Mobile 2 on Amazon right now for $130, though the reviews aren’t exactly stellar. They continue to offer a single chip EEG sensor (datasheet, PDF) that you can integrate into your projects as well, the daughterboard for which looks remarkably similar to what’s in the Mindflex headset. Despite the shaky response to the devices that have hit the market so far, it seems that NeuroSky hasn’t given up on the dream of bringing affordable brain-computer interfaces to the masses.